200 Years

Explore the history of Trinity College, from our founding in 1823 to our exciting future at the dawn of our third century.

1823-77: Founding the College

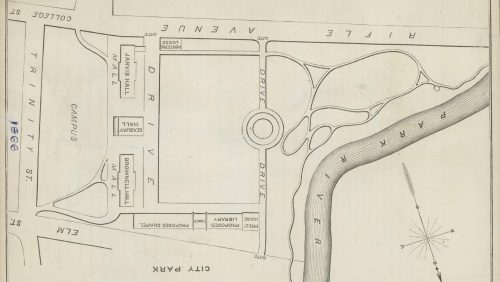

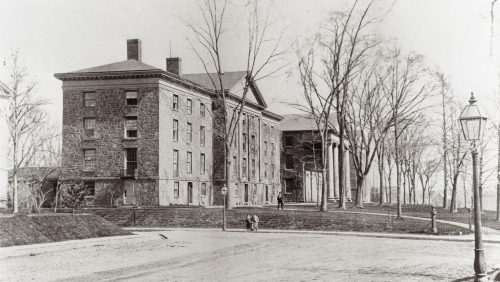

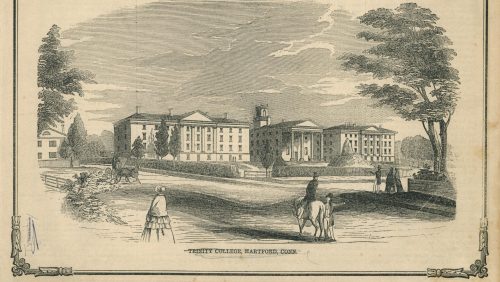

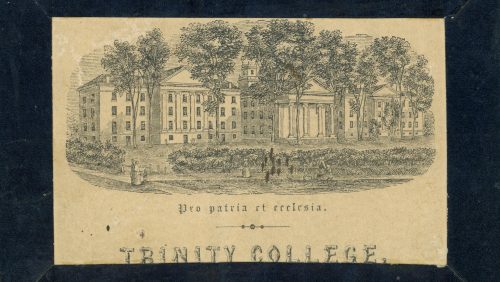

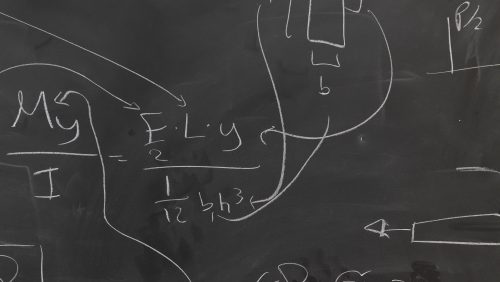

In 1823, the Connecticut General Assembly approved a petition to charter a college, so named “Washington College” in honor of the nation’s first president.The state’s second college after Yale, it welcomed nine students in the first academic year. In the early years, about a third of the scholars came from outside of New England to enroll in the three-term academic calendar, at $14.50 per term. Student housing boasted rooms 12-by-20 feet, each with a Franklin stove for heat. When forced indoors, the popular activity was log throwing. Lecture rooms were illuminated by kerosene lamps, but the dearth of lighting in the student quarters was a topic for the first student newspaper, The Tablet. Editors were unafraid to push boundaries, publishing their support for the “co-education of the sexes” in 1868. In class, a rigorous curriculum included lively exchanges about Latin and Greek, arithmetic, the sciences, and philosophy. Outside of class, students formed a Chapel choir and established Greek life, along with rowing, baseball, and football teams. On all matters, students were clearly outspoken and determined to right injustices. In the summer of 1828, undergraduates barricaded the College’s two existing buildings to the faculty because of a perceived town-gown wrong. Hartford grew alongside the College, which changed its name in 1845 to avoid confusion with other institutions named after George Washington. In 1872, the city eyed the College’s downtown campus for a new, larger State Capitol. But it took the city nearly doubling its original offer to $600,000 before the Board of Trustees agreed to sell. It was the end of an era.

Year to Year

Brownell Leads Petition to Found College

Episcopal Bishop Thomas Church Brownell assembles interdenominational group to petition Connecticut legislature for college.

General Assembly Approves Washington College

Governor signs charter for nonsectarian Washington College, named in honor of first U.S. president.

Charter Day![Related images Related images "Washington Campus." Students with horse-drawn carriage, Trinity College Old Campus, Hartford, Connecticut "Washington Campus." Students with horse-drawn carriage, Trinity College Old Campus, Hartford, Connecticut unknown American (photographer) ca. 1860 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Chapel (Seabury Hall), Trinity College old campus, Hartford, 1876 Chapel (Seabury Hall), Trinity College old campus, Hartford, 1876 unknown American (photographer) 1876 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Students in Jarvis Hall, Trinity College, Hartford, CT Students in Jarvis Hall, Trinity College, Hartford, CT ca. 1960s Part of Trinity College Archival Images 10th Anniversary of Coeducation at Trinity College, panelists and audience [Coeducation] 10th Anniversary of Coeducation at Trinity College, panelists and audience [Coeducation] Unknown photographer 1979 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Bishop Brownell statue on the old campus (Trinity College, Hartford Conn.) Bishop Brownell statue on the old campus (Trinity College, Hartford Conn.) Unknown American Photographer Part of Trinity College Archival Images Williams Memorial Hall, Trinity College, Hartford, CT Williams Memorial Hall, Trinity College, Hartford, CT Burges, William (English architect and designer, 1827-1881) ca. 1918 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Façade of Trinity College Old Campus buildings: Jarvis Hall (1825-1878), Seabury Hall (1825-1878) and Brownell Hall (1845-ca.1877) Façade of Trinity College Old Campus buildings: Jarvis Hall (1825-1878), Seabury Hall (1825-1878) and Brownell Hall (1845-ca.1877) unknown American (photographer) ca. 1860 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Baseball team, including John Henry Kelso Davis '99 (seated on bench, third from left) and Reggie Fiske '01 (seated on bench, second from right), Trinity College, Hartford, CT [Athletics] Baseball team, including John Henry Kelso Davis '99 (seated on bench, third from left) and Reggie Fiske '01 (seated on bench, second from right), Trinity College, Hartford, CT [Athletics] Unknown photographer 1899 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Alumni Hall Fire (Trinity College, Hartford CT) Alumni Hall Fire (Trinity College, Hartford CT) Unknown photographer 2/1922, built 1887 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College Old Campus viewed from Bushnell Park with Park River in foreground, Brownell Hall (1845-c.1877) visible in background Trinity College Old Campus viewed from Bushnell Park with Park River in foreground, Brownell Hall (1845-c.1877) visible in background Dudley, William G. (photographer, American, act. 1865) 1865 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College old campus. The campus and the lake at the Commencement Season Trinity College old campus. The campus and the lake at the Commencement Season unknown American (photographer) ca. 1870 Part of Trinity College Archival Images View of Trinity College Long Walk [upper left corner] looking southwest from Capitol Building, Hartford, Connecticut View of Trinity College Long Walk [upper left corner] looking southwest from Capitol Building, Hartford, Connecticut unknown American (photographer) ca. 1885 or 1893 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College Old Campus Buildings from College Street (now Capitol Avenue) at the head of Trinity Street, 1870 Trinity College Old Campus Buildings from College Street (now Capitol Avenue) at the head of Trinity Street, 1870 unknown American (photographer) 1870 Part of Trinity College Archival Images Main quad and Bishop Brownell Statue from Northam Towers, Trinity College (Hartford, Conn.) Main quad and Bishop Brownell Statue from Northam Towers, Trinity College (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College Chapel (Hartford, Conn.) Trinity College Chapel (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College, Chapel and Williams Memorial (Hartford, Conn.) Trinity College, Chapel and Williams Memorial (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College, Clement Chemistry Building (Hartford, Conn.) Trinity College, Clement Chemistry Building (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Long Walk, Trinity College (Hartford, Conn.) Long Walk, Trinity College (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College, Bishop Brownell Statue (Hartford, Conn.) Trinity College, Bishop Brownell Statue (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Trinity College, Jarvis Hall, Williams Memorial and Chapel (Hartford, Conn.) Trinity College, Jarvis Hall, Williams Memorial and Chapel (Hartford, Conn.) Unknown American (photographer) ca. 20th century Part of Trinity College Archival Images Related text The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity JOURNAL ARTICLE JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 164, No. 2 (JUNE 2020), pp. 118-142 "I'd Like to Dance Like a Madman": Flamenco and Surrealism "I'd Like to Dance Like a Madman": Flamenco and Surrealism JOURNAL ARTICLE Analisa Leppanen Art Journal, Vol. 78, No. 3 (FALL 2019), pp. 30-59 Art, Science, Invention: Conservation and the Peale-Sellers Family Art, Science, Invention: Conservation and the Peale-Sellers Family JOURNAL ARTICLE Renée Wolcott Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 108, No. 1, Art, Science, Invention: Conservation and the Peale-Sellers Family (2019), pp. i, iii-ix, xi-xx, 1-55, 57-99, 101-170, 171-174 A Mid-Century MONOLITH in Northwestern Montana: The Hungry Horse Dam Project A Mid-Century MONOLITH in Northwestern Montana: The Hungry Horse Dam Project JOURNAL ARTICLE Charlene Roise Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 68, No. 2 (Summer 2018), pp. 45-58, 94-96 A Visual Genealogy of a Sacred Landscape A Visual Genealogy of a Sacred Landscape JOURNAL ARTICLE Noa Hazan, Avital Barak Israel Studies Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, SPECIAL ISSUE: Changing Perspectives on the Temple Mount (Summer 2017), pp. 20-47 This is the metadata section. Skip to content viewer section. Trinity College logo IMAGE "Washington Campus." Grounds of Trinity College Old Campus, Hartford, Connecticut](https://www.trincoll.edu/bicentennial/wp-content/uploads/sites/145/2023/04/10.2307_community.33120315-1-500x282.jpg)

Hartford Donations Secure Location

Trustees vote to be in Hartford (not Middletown or New Haven) because residents contribute $20,000+ for the institution. Brownell elected president; 14 acres downtown acquired. Classes start with 3:1 student-teacher ratio for students ages 15+.

Chapel Choir Organized

The Chapel Choir (later The Chapel Singers) is organized, making it the oldest continuously active student organization.

Two Buildings Erected

First two buildings—Seabury Hall (lecture rooms, library, natural history museum, chapel) and Jarvis Hall (dorm)—open.

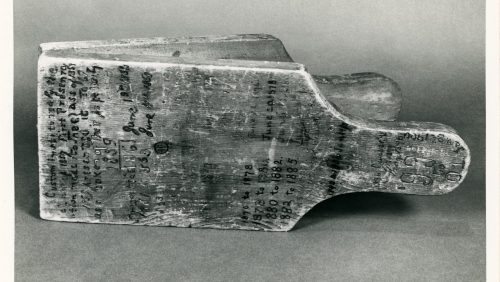

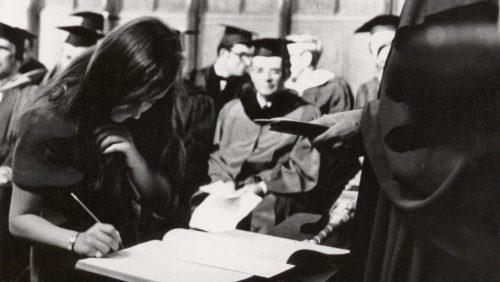

Matriculation Book Debuts

Signing the book as an act of enrolling at the College begins, making it the oldest continuously observed tradition.

First Commencement

The College confers 10 bachelor’s degrees, two master of arts degrees, and an honorary doctor of laws degree. However, the first degree was awarded a year earlier. In 1826, Scottish Bishop Alexander Jolly received doctor of divinity, first degree overall and first honorary degree conferred.

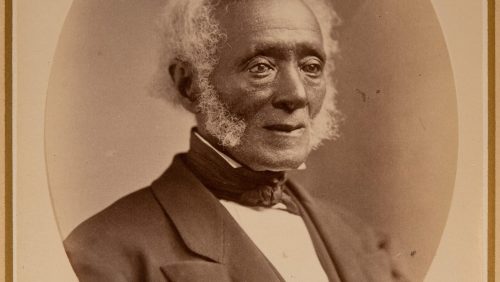

First Black Student Earns Degree from the College

Episcopal Rev. Edward Jones, first Black alum of Amherst College, earns master’s from Washington College, and goes on to lead a university in Sierra Leone.

Alumni Association Established

The first formal alumni association, the Association of Alumni, is established.

Name Changed for Clarity

Trustees petition the Connecticut General Assembly for name change to Trinity College to prevent confusion with four other institutions.

Administration Expands

Major changes to administrative structure occur, including appointment of chancellor, Board of Fellows, House of Convocation.

Oldest Academic Society Takes Root

Beta CT Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa inducts about five students in senior class (one-third of class) each year in the 1850s.

Lemon Squeezer Debuts

Class of 1857 presents lemon squeezer to Class of 1859, honoring James “Professor Jim” Williams, who used one to make punch.

History of Hijinks

Terms Cut to Two

The three academic terms—named Advent, Lent, and Trinity in 1847—are reduced to two: Christmas and Trinity.

![Two crew teams rowing on the water, Trinity College, Hartford, CT [Athletics]](https://www.trincoll.edu/bicentennial/wp-content/uploads/sites/145/2023/03/10.2307_community.24948857-1-scaled-1-500x282.jpg)

Intercollegiate Rowing Starts

Trinity joins Brown, Harvard, Dartmouth, Yale to start College Union Regatta, likely country’s first such rowing association.

Trinity Men Fight in Civil War

At least 105 Trinity men serve in Union, Confederate forces. Sixteen die, including two brigadier generals in Union Army.

America's Favorite Pastime

After the Civil War, baseball became the College’s most popular sport. By the spring of 1866, Trinity had its own varsity team.

Student Clubs Enter Politics

In the presidential election, the Grant Club campaigns for Ulysses S. Grant and the Democratic Club for Horatio Seymour.

Dramatic Society Founded

The Dramatic Society, the first of its kind at the College, introduces the campus to student theater performances.

First Student Publication Appears

The Trinity Tablet appears 1868 and was published 12 times a year until its final issue in 1908.

Trinity Inks Agreement to Move

Trustees accept Hartford’s $600,000 for College’s downtown site to become State Capitol. Relocation planned for 1878.

Room for Growth

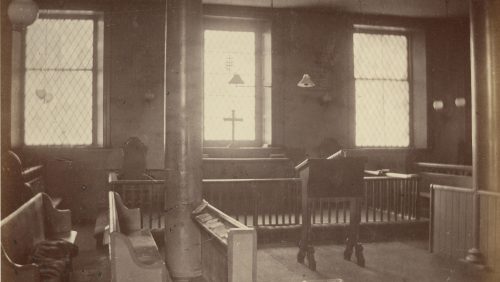

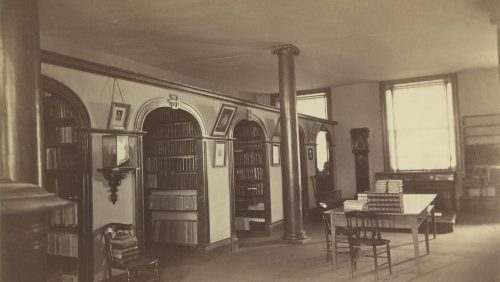

Early Student Housing

Early images of student rooms reflect the times, with fixtures such as stoves for heat. But they also show us what is timeless.

Explore Gallery

Enrollment Milestone Reached

Student enrollment reaches 100 for the first time.

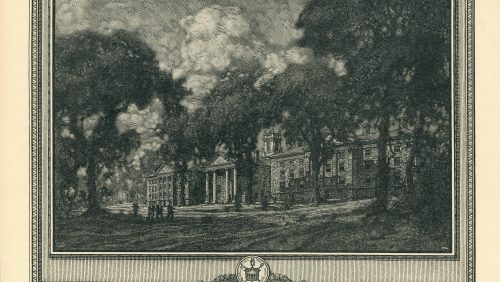

1878-1930: Establishing Traditions

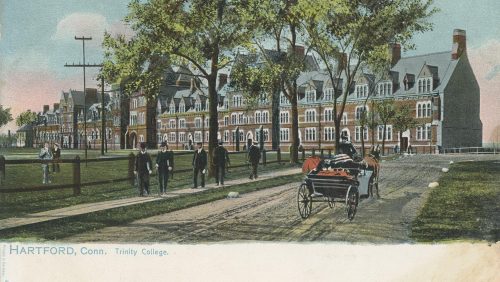

When Trinity first moved to its home on Summit Street, campus life was largely as it had been in downtown. Even the statue of the College’s first president, Bishop Brownell, would relocate to the new site.A row of elm trees in front of the Long Walk took root, and new amenities offered comfort. Electricity, hot water, and telephone service were installed. A flagpole went up in front of Northam Towers and, nearby, a sundial. The Bantam mascot, blue-and-gold colors, and The Tripod were introduced, becoming a foundation for campus identity. During his senior year, Augustus P. Burgwin ’82 set the words for the unofficial alma mater, “’Neath the Elms of Our Old Trinity,” to the tune of an old African American spiritual. But beyond the green and occasionally muddy swath of the Main Quad, the world was getting smaller. World War I raged. By June 1917, one-fourth of the student body was in military service. Around the globe, the influenza pandemic caused destruction. Trinity’s 1923 centennial celebration included a memorial service for Trinity’s losses. In one significant way, Trinity was changed forever: the College had received students from all five major regions of the world. Trinity students were a globally connected community.

Year to Year

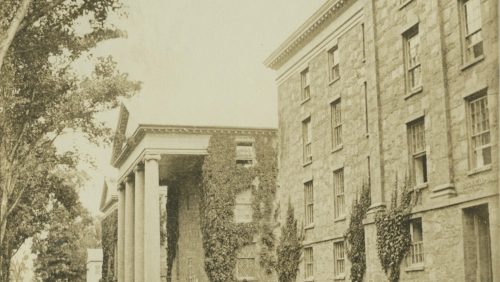

Long Walk Opens

Summit Campus opens three buildings: Seabury Hall, Jarvis Hall, and Northam Towers. Seabury, Jarvis occupied by fall 1878.

‘They Should Stand for Ages’

Founder's Statue Relocates

The iconic statue of Bishop Brownell was relocated to the Summit Campus from the original site.

Read on

College Legend ‘Professor Jim’ Dies

Formerly enslaved James Williams, 88, employed as laborer for 50 years, dies. Overflow crowd attends his service.

Main Quad Takes Shape

Elm trees planted in rows—one along Long Walk, two running east from Northam—to form “T.” Brownell statue moved to Main Quad. And the first telephone service is installed. The campus takes shape.

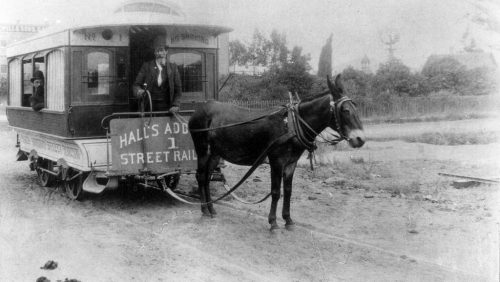

Public Transportation Creates Link

A horse railway service from downtown Hartford to Broad and Vernon streets begins operation.

Senior Pens ‘’Neath the Elms’

Augustus Burgwin ’82 sets words for “’Neath the Elms of Our Old Trinity”; it is unofficially adopted as alma mater by 1900. Listen to the Chapel Singers perform the piece.

Blue and Gold Rule

Undergraduates make the case to change school colors from green and white (adopted in 1868) to dark blue and gold. And in a letter to alumni, the Trinity College Athletic Association argues for more adequate facilities for athletics.

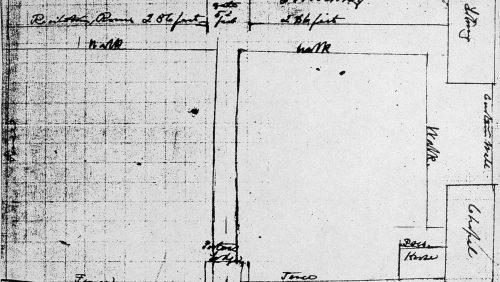

Olmsted Influence

The student newspaper credits the Main Quad plantings to Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted. While no official renderings exist to indicate the renowned landscape architect designed campus, a pencil drawing indicates his influence,

Lawn Tennis Grows

Trinity is charter member of Intercollegiate Lawn Tennis Association with Yale, Brown, and Amherst.

President's House Completed

The former president’s house at 115 Vernon Street is completed, converted to the English Department in late 1970s.

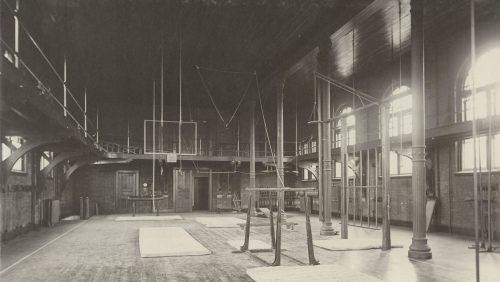

Alumni Hall, Jarvis Physical Lab Open

Alumni Hall houses gym; Jarvis Lab facilitates physics, chemistry. Jarvis demolished in 1963; Alumni Hall burns down in 1967.

Modern Comforts on Campus

Electricity and steam heating are installed on the Main Quad.

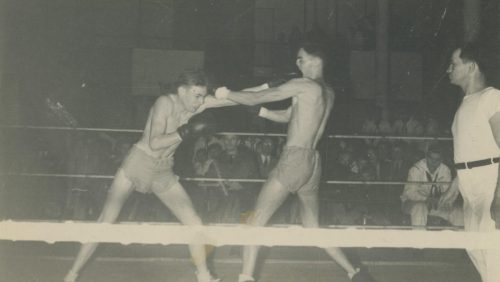

Basketball Begins Competition

Basketball was introduced 1894 when the men won their first game against Hartford Public High School at the local YMCA.

Track and Field Team Debuts

The sport existed as far back as the 1880s but the men’s team officially formed in 1895.

Banty Brainstormed in Dinner Talk

Joseph Buffington ’75 envisions a bantam mascot in the “collegiate barnyard,” ready to take on the Princeton tiger and Yale bulldog. The idea soars.

The Bantam

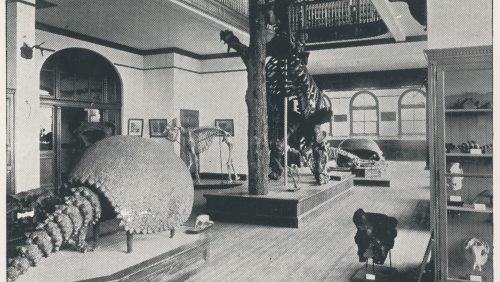

Flora, Fauna Found in New Museum

Hall of Natural History opens teaching museum of animal, plant specimens from across globe; building is torn down in 1971.

Beanie to Be a Six-Decade Tradition

Sophomores require freshmen to wear beanie (small cap), a tradition until its demise with coeducation in 1969.

Conspicuous CapFirst Woman Receives a Degree

Caroline Hewins, Hartford Public Library librarian, is first woman to receive degree (honorary master of arts).

Undefeated

In 1911, the Trinity College football team would record its first undefeated season.

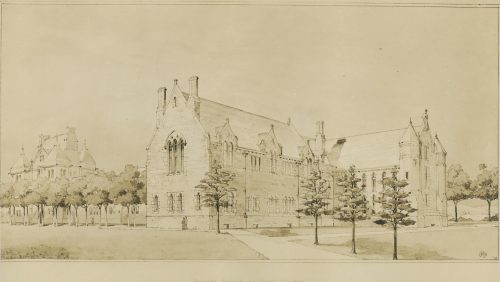

Williams Memorial Completed

Williams Memorial completed at 90-degree angle to Jarvis Hall, in nod to original architect’s quadrangle plan.

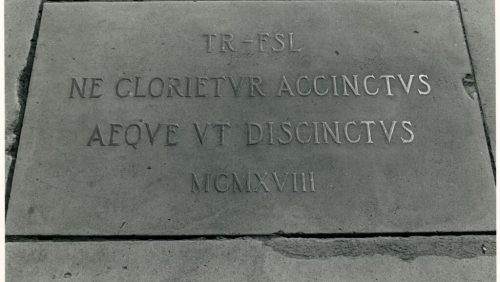

Roosevelt: Our Business Is to Win War

Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt gives speech against pacifism, receives honorary degree. Long Walk plaque marks visit.

Set in Stone

On Campus, Individuals Train for War

More than 480 students, alumni serve in World War I. Students on campus, about 172 men, in Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.).

World War I

Centennial Celebration

In June of 1923, the Centennial Celebration began in earnest.

Explore Gallery

Alumni Hall Ablaze

The building was the target of one of six fires on campus in February 1923.

An Unsolved Mystery

College Charts Global Path

By 1925, students from all five major regions of the world had matriculated at Trinity.

International Reach

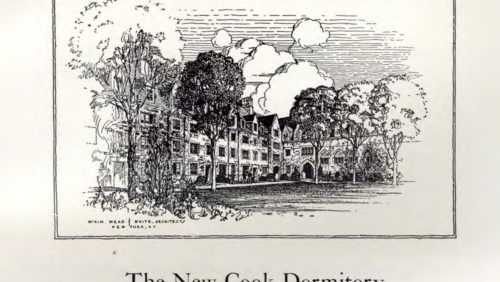

Centennial Funds Drive Building Campaign

Campaign funds new structures: Trowbridge Pool/Squash Facility, Cook Dormitory, Cook Commons, and new chemistry building.

Two Women Earn Master’s

Anne L. Gilligan and Dorothy M. McVay, teachers from Hartford Public Schools, are first women to earn graduate degrees.

1931-66: Expansion and Mid-Century Trinity

The proclamation that World War I was the “war to end war” was never realized as international diplomacy gave way to the destruction of World War II.At Trinity, The Tripod published stories on alumni who received Purple Hearts. Servicemen returned home, filling student housing and stretching classes to capacity. Campus buildings multiplied and reached skyward, in the case of the Chapel and clock tower. And Trinity bestowed an honorary degree on Dwight D. Eisenhower, the first sitting president to visit the College. The future began what would be a prolonged tug-of-war with the past. Emblematic of that, students achieved a decades-long goal to do away with nearly all mandatory religious services. And, they established several clubs reflecting the diversity of religious views on campus: Roman Catholic, Jewish, Protestant, and Episcopalian. WRTC launched, too, providing live broadcasts from campus including one featuring the speech by popular poet Robert Frost.

Year to Year

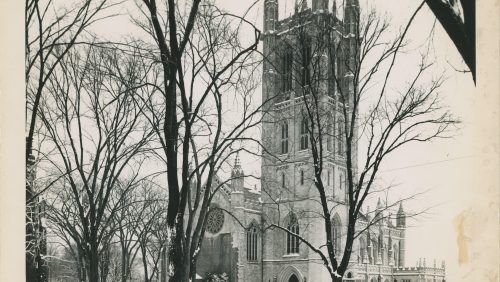

National Cathedral Architect Designs Chapel

New Chapel dedicated as gift by William G. Mather ’77; Austin organ installed; 30-bell carillon given by Rev. John F. Plumb and wife.

Historic Space Continues to be Key Part of Campus Life

Cook Dormitory Opens

The Cook Dormitory, necessitated by increasing enrollment, was made possible by funds from Charles W. Cook.

Several Clubs Established

Newman Club (Roman Catholic), Canterbury Club (Episcopalian), Hillel (Jewish), and Protestant Fellowship begin; Interfaith Council formed.

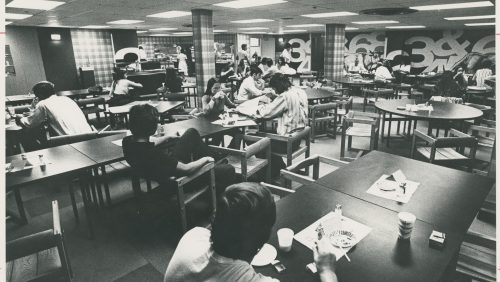

Student Body Exceeds 500

By the late 1930s, the number of undergraduates in the student body exceeds 500 for the first time.

New Space for Growing Student Population

Goodwin-Woodward Dormitory and Ogilby Hall open to accommodate growing undergraduate population.

Curriculum Modified for Naval Training

U.S. Navy begins on-campus training for World War II officers; 900 apprentice seamen, 300 civilian students take part.

Word War II

G.I. Bill Spurs Year-Round Classes

After war, Trinity expands to 900 students; three-quarters are veterans on G.I. Bill. College temporarily goes year-round.

College Hires First Chaplain

Trinity hires first chaplain so religious services are no longer led by presidents, faculty members, or visiting clergy.

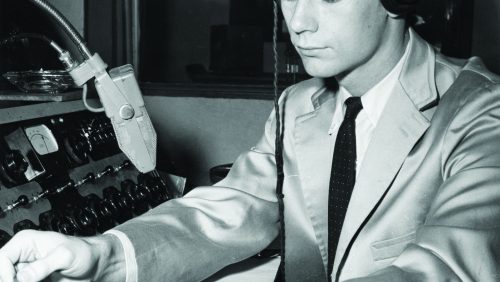

WRTC Goes Live

WRTC begins live radio broadcasts from Jarvis. Among first performers are The Pipes, Trinity’s first a cappella group, founded in 1938.

On Air

Campus Mainstay

The Cave is established in 1948 as a place for students to have some coffee, play bridge, and socialize after hours.

The Cave

Parties both Formal and Informal

As Greek-letter societies at Trinity transitioned from “secret societies” to modern fraternities, the public aspect of Greek life began to expand. In the 20th Century, the fraternity dances became high points of the College’s social calendar.

Explore GalleryFirst Black Student Graduates

Kenneth Higginbotham earns B.A. in history, attends Yale’s Berkeley Divinity School, serves as canon in Episcopal Diocese of L.A.

Professor’s Business Idea Sticks

Vernon K. Krieble, Scovill Professor of Chemistry, develops industrial sealant Loctite, later a multimillion-dollar global enterprise.

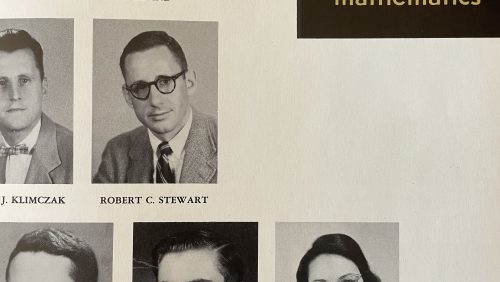

First Woman Appointed to Faculty

Actuarial mathematics specialist Marjorie V. Butcher was named part-time lecturer, then associate professor in 1974, full professor in 1979.

Marjorie ButcherItalian Studies Introduced

Professor Michael R. Campo ’48 spearheads Cesare Barbieri Center for Italian Studies (now Cesare Barbieri Endowment for Italian Culture).

Downes Clock Tower Completed

Built to house administrative offices, Downes Memorial Clock Tower completes enclosure of north side of Main Quad.

Robert Frost Guest Speaker

WRTC records Robert Frost’s speech to 1,200 students at Memorial Field House and The Reporter documents a day with the popular poet.

Trinity Students in Solidarity

Jack Chatfield ’64, Ralph Allen ’64 jailed for registering Black citizens to vote. Chatfield freed; rally at State Capitol demands Allen’s release.

Austin Arts Center Opens

Austin Arts Center (theater, dance, music; performance spaces; galleries) opens in honor of Fine Arts Department founder A. Everett Austin Jr.

Mandatory Religious Services Eliminated

In 1959, religious services are mandatory only on Sundays. They are eliminated six years later.

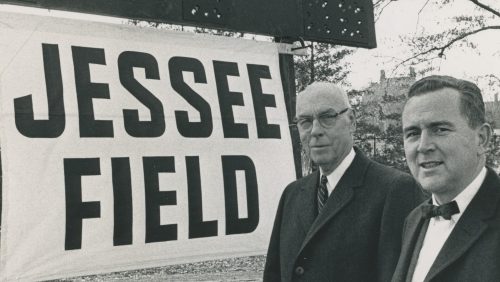

Jessee Field Named for Winning Coach

Trinity Field renamed Jessee Field to commemorate Coach Daniel Jessee, who reached 150 career wins in his last game vs Wesleyan. Jessee coached from 1932-1966.

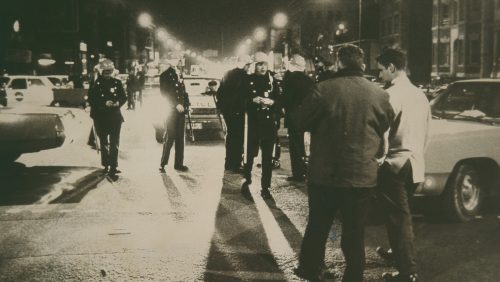

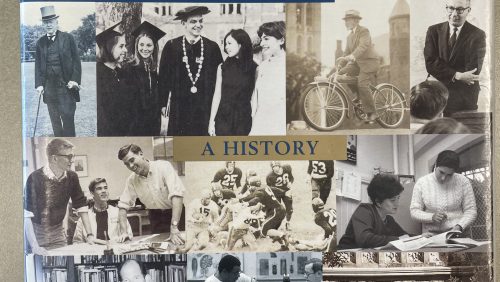

1967-85: Times of Change

During this era, Trinity celebrated its 150 years of growth and endured growing pains. As a nation, battles were waged on the home front.Young people rejected notions that had long shaped the student body. Classes began to top 300 students and to demand equal representation. Citing the lack of adequate scholarship assistance for Black students at Trinity, approximately 168 undergraduates engaged in a protest that temporarily prevented members of the Board of Trustees’ Executive Committee from leaving their meeting. Coeducation became a reality as the first women students signed the Matriculation book. At the same time, campus facilities and programs continued to proliferate. The Albert C. Jacobs Life Sciences Center and the George M. Ferris Athletic Center opened, and Cinestudio and the Rome Program launched. Trinity joined the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC), forging a path for new student records and feats. But first, a generation rose up against a war they rejected.

Year to Year

Students Form Trinity Association of Negroes

Group recognized, sparking talks on whether Trinity is welcoming to Blacks. Name changed to Trinity Coalition of Blacks in 1968.

Snapshot of a Reunion

Over the years, the size of the Reunion and Commencement gatherings grew and the events needed to be scheduled on separate weekends.

Explore Gallery

Martin Luther King Jr. Assassinated

About 800 students flood Trinity’s Chapel to memorialize Martin Luther King Jr.

Activists Stage Sit-in for Scholarships

Citing lack of financial aid for Black students, sit-in staged at Downes, Williams for 30+ hours. Scholarships for Black students increase.

The Sit-in and its Aftermath

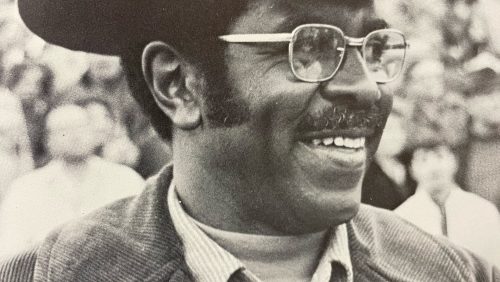

First Black Upper Administrator Hired

E. Max Paulin is first Black admissions administrator. At Trinity 1968–78, he becomes assistant director of admissions.

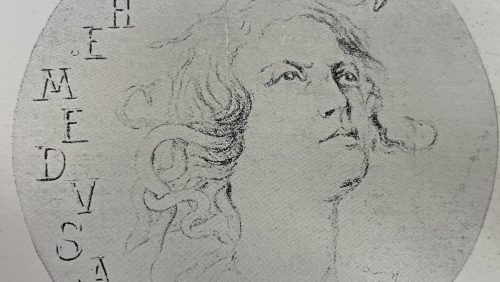

Student Society ‘Medusa’ Ends

Medusa, secret student society in charge of student discipline, loses disciplinary function; in 1969, ends run as recognized group.

Civil Rights Leader Addresses Community

Civil rights leader Julian Bond gives talk in Krieble Auditorium. As NAACP chair in 2002, Bond delivers speech in Mather.

Women on Campus

Coeducation has led not only to women students accounting for half of the student body and almost half of the faculty but also to women at the very top echelons of the college.

Explore Gallery

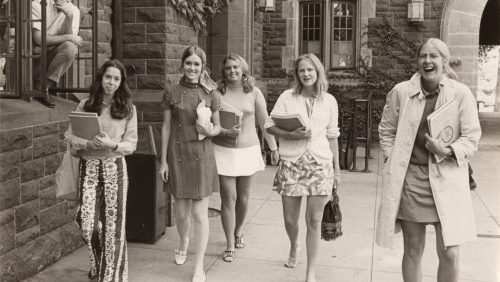

Coeducation Approved, Women Arrive

In the fall of 1969, Trinity College welcomed a new class of fiercely determined and intellectually impressive students. For the first time, some of them were women.

Pioneers

Cinestudio Opens, Stands Test of Time

Cinestudio thrives as cultural asset despite changes in film–viewing habits.

Moving Pictures

New Sciences, Athletic Centers Open

Albert C. Jacobs Life Sciences Center and the George M. Ferris Athletic Center open.

Rome Campus Adds International Dimension

The College inaugurates the Rome Program, the inspiration of Professor Michael R. Campo ’48.

When in Rome

First Black Woman Appointed to Faculty

Ann E. Robinson starts as assistant professor of psychology, making her the first Black female appointed to faculty.

Umoja House’s Predecessor Formed

College designates Black Cultural Center. It is renamed Umoja House in early ’80s.

Athletics Offers Women Access to Sports

After a year in which female students run their own teams, Trinity athletics gives women access to intercollegiate sports.

Explore Gallery

Two Female Students Mark Firsts

Laura S. Sohval is first female salutatorian. Thelma Marie Waterman is first Black female accepted to Trinity.

New Option to Degree

Individualized Degree Program, for students pursuing degrees outside four-year track, starts, then gains popularity.

Individual Degree Program

Trinity Joins Athletic Conference

Students begin to compete with other schools in the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC).

Women Achieve More Faculty Firsts

Dori Katz named to Modern Languages Department, becomes the first woman to hold tenure-track position and to be granted tenure. Watch an interview with the professor emerita.

New Organ Premieres

New organ dedicated in Chapel by Mrs. Newton C. Brainard. Retired music professor, organist Clarence E. Watters gives concerts.

Adding Their Voices

On April 21, 1972, the students voted to protest the war in Vietnam.

First Women’s Student Group Formed

Trinity Women’s Organization (TWO) formed as forum for concerns of women on campus. Betty Friedan, Ruth Bader Ginsberg lecture.

Latin American Group Founded

La Voz Latina founded to build awareness of Latin American culture, politics, social issues. Cultural house La Eracra opens in 1999.

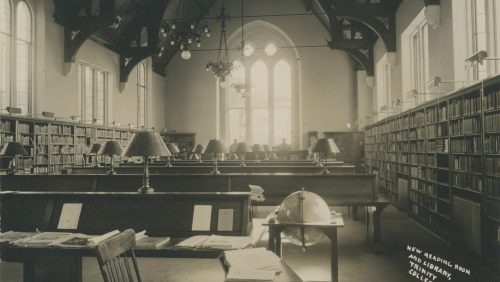

Knowledge Growth

When Trinity moved to the Summit Campus, 18,000 library books moved into Seabury Hall. But the library quickly outgrew the space.

Explore GalleryTrinity Joins Neighborhood Alliance

Trinity joins what will be Southside Institutions Neighborhood Alliance (SINA), focusing on needs of those at or near College.

Women’s Center Formed as Resource

The Women’s Center, now Women and Gender Resource Action Center, opens and briefly publishes Feminist Scholarship Review.

Black Women’s Group Brings Jesse Jackson

Trinity Coalition of Black Women Organization (TCBWO) is established, co-sponsors speech by Rev. Jesse Jackson before 1,500.

Traveling in Style

Public transportation is a facet of urban living. But through the years, Trinity community members and visitors navigated the region in many other vehicles, too.

Explore GalleryWomen's Volleyball Debuts as Club

Women’s Volleyball began as a club sport under Coach Robin Sheppard. The team achieved varsity status in 1985.

New Support Given for LGBTQ+

The Lesbian and Gay Issues Committee composed of faculty, students, and alumni is formed by student Kim Carey ’89.

1986-2000: New Dynamism, New Challenges

During this time, Trinity College began to reflect a growing diversity. The first female dean of the faculty and first Jewish president—Jan Cohn and Evan Dobelle, respectively—were appointed.Another first, Trinity’s dean of multicultural affairs, supported greater diversity at the College. Community was celebrated. Trinity pioneered a neighborhood revitalization effort that resulted in the “Learning Corridor.” And the College launched Dream Camp to host underserved youth in a free academic summer program. At the same time, the curriculum became more international in content and orientation. The accomplishments of world leaders such as former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the Rt. Rev. Desmond M. Tutu were recognized with honorary degrees. The future and the past were revered. The Board of Trustees recognized the need to bring the library into the 21st century by launching a $32 million renovation project. The College’s history was embraced with the publication of a new book by the then-Trinity archivist.

Year to Year

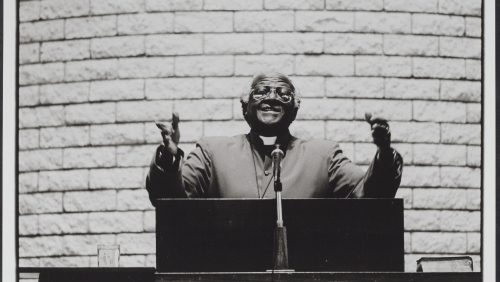

Desmond Tutu Awarded Honorary Degree

President James F. English Jr. confers honorary degree on Desmond Tutu, Anglican bishop of Johannesburg, Nobel Prize laureate.

Divestment from South Africa Begins

The College starts to divest itself fully of all investments in corporations conducting business in South Africa during apartheid.

N.Y.C. Performing Arts Program Starts

The Trinity/La Mama Performing Arts Program begins at the La Mama Experimental Theatre Club in New York City.

Arts ImmersionFirst Woman Dean of Faculty Named

Professor of English Jan Cohn appointed dean of the faculty, the first woman to hold the position, serving until 1994.

Asian Awareness Week Debuts

The first Asian Awareness Week is hosted on campus by ASIA (Asian Students International Association).

Racial Harassment Policy Adopted

Tom Gerety, Trinity’s first Roman Catholic president, introduces policy against racial harassment, creates Racial Harassment Committee.

Mathematics, Computing, Engineering Move

Funds from $50 million campaign go to Mathematics, Computing, and Engineering Center (MCEC), which opens for classes, lab work.

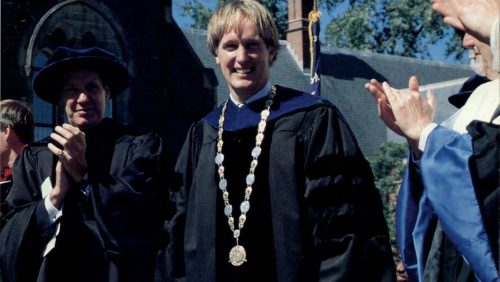

First Jewish President Appointed

Evan S. Dobelle becomes the first Jewish person to serve as president of Trinity College.

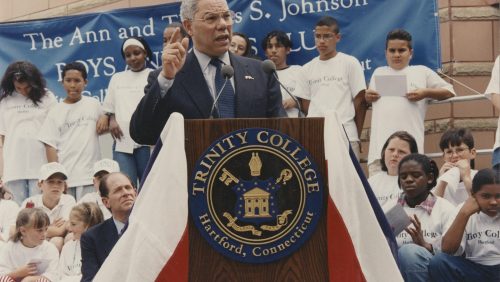

Public Schools, Spaces Developed Nearby

A neighborhood revitalization effort spearheaded by Trinity and supported by local entities creates the Learning Corridor, which brings together the Trinity College Boys and Girls Club and four schools. Colin Powell, retired Four-Star General, speaks at the dedication.

Community of Learning

Engineering Turns 100

100 years of engineering instruction celebrated; Trinity one of two U.S. liberal arts colleges to have accredited engineering program.

Human Rights Program Established

Human Rights Program promotes student awareness, facilitates courses in disciplines that address human rights issues.

A Groundbreaking Program

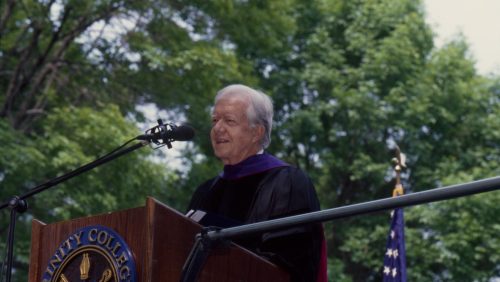

Jimmy Carter Gives Commencement Address

Former President Jimmy Carter delivers the Commencement address and receives an honorary degree from the College.

Dream Camp Becomes Reality

Dream Camp hosts underserved youth in free academic summer program. About 170 Hartford children participate each session.

Dream Camp

Lower Long Walk Is Completed

The project is the first to be pursued in Phase 1 of the Campus Master Plan.

World Conference on Carnival Hosted

The event brings famous performers and artists to campus and highlights the culture of Trinidad and Tobago.

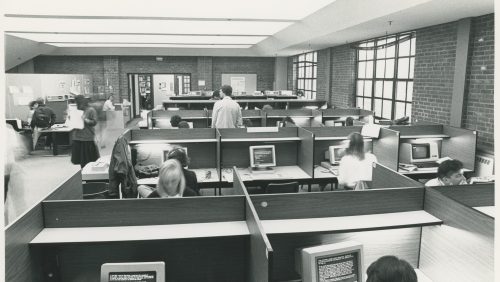

Library Slated for Renovation

Trustees OK $32 million renovation of library, built in 1952 and expanded in 1977. Spaces to have wired, networked computer connections.

Asian American Students Association Formed

Asian American Students Association (AASA) acquires cultural house, promotes education, awareness, appreciation for cultures.

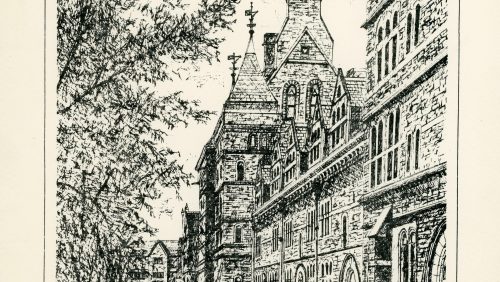

Trinity History Showcased in 569 Pages

Trinity College in the Twentieth Century, by archivist Peter J. Knapp and wife Anne H. Knapp, is published.

2001–Present: 21st Century Growth

With a new master plan in place, the campus took shape into the Trinity we know today.Changes included the renovations of the Gates Quad and the Long Walk, and the addition of new buildings for the Admissions and Career Development Center and the Koeppel Community Sports Center. When terrorists attacked the nation on September 11, 2001, Trinity’s foundation felt tremors through the community. It was the first of two events that caused shifts in paradigms during this era. The other, the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitated new ways of living and learning. At the same time, new musical traditions began in the form of the Trinity International Hip Hop Festival and Samba Fest. Soon after her arrival, President Joanne Berger-Sweeney put a new focus on the first-year student experience with the introduction of the Bantam Network. Trinity joined a shift in college admissions by making test scores optional on applications. Under the strategic plan, Summit, Trinity enhanced its relationships with Hartford by embracing innovative partnerships, opening multiple spaces downtown, and forming the Center for Hartford Engagement and Research. Looking to the future, the Trinity Plus curriculum and a recommitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion furthered the College’s goals and ideals as it prepared to enter its third century.

Year to Year

Campus Master Plan Takes Shape

In Phase I of Campus Master Plan, admissions building is completed, arch at Northam Towers opens as grand entrance to quad.

Zachs Hillel House Opens

Donated by Trustee Henry Zachs ’56, Zachs Hillel House opens, hosting Jewish activities. Vernon Street becomes a cultural and social hub on campus.

Zachs Hillel House: ‘A Wonderful Place to Gather’

September 11

The 9/11 terrorist attacks take the lives of six members of the Trinity community.

September 11, 2001, Affects Trinity Community

World-Class Squash Center Opens

George A. Kellner Squash Center opens with first squash courts in world to have walls of colored—not clear—glass to cut distractions.

State-of-the-Art George A. Kellner Squash Center Opens

Raether Center Dedicated

Expanded library renamed Raether Library and Information Technology Center, honoring Paul E. Raether ’68, H’14, P’93, ’96, ’01.

Bricks & Clicks: The Evolution of the Raether Library and Information Technology CenterIslamic Chaplaincy

Trinity establishes an Islamic chaplaincy to serve as a resource for Muslim and non-Muslim students alike.

Queer Resource Center

The Queer Resource Center (QRC) inaugurated at 114 Crescent Street. The center serves as hub for LGBTQ+ student life.

Queer Resource Center Is Campus Hub for LGBTQ+ Life

Trinity International Hip Hop Festival Debuts

Founded by Magee McIlvaine ’06 and Jason Azevedo ’08, festival hosts music, dance performances, promotes social justice, racial equity.

A Trinity Treasure: The Trinity International Hip Hop Festival

Samba Fest Begins

A samba festival—now Samba Fest—begins, drawing musical groups from across the globe, notably Brazil, and from Hartford area.

Samba Fest Connects Cultures and Communities

Ice Rink Is for Trinity, the Community

Koeppel Community Sports Center opens, with Albert C. Williams ’64 Skating Rink home to Bantam hockey, neighborhood recreation.

Koeppel Community Sports Center

The Long Walk Restored

Yearlong, $32.9-million renovation of Long Walk preserves historic, architectural integrity of buildings, adds modern amenities.

The New Long Walk: $32.9 Million Restoration Completed in 2008

‘The White Paper’ Released

President James “Jimmy” Jones Jr. proposes major reforms to be enacted within 10 years, including changes to Greek life.

‘The White Paper’

Gates Quad Reshaped

Quad in front of Mather Hall redeveloped with new lighting, walkways, lawn; renamed Gates Quad in honor of John Gates Jr. ’76.

Gates Quadrangle Reshaped

‘The Streak’ That Can’t Be Squashed

Under Head Coach Paul Assaiante, the Trinity men’s squash team completes the longest winning streak in college sports history.

‘The Streak’ That Can’t Be Squashed

New Housing, Renovated Social Space Open

The apartment-style Crescent Street Townhouses open, and Vernon Social Center renovations are completed.

New Housing, Renovated Social Space Open

President Joanne Berger-Sweeney’s Inauguration

Joanne Berger-Sweeney is the first woman, first African American, and first neuroscientist to become Trinity president.

President Joanne Berger-Sweeney

Bantam Network Creates Connections

Initiative aims to create immediate sense of belonging by encouraging connections among new students, their peers, mentors.

The Bantam Network: Helping First-Year Students Find Their Footing

Holistic Approach to Admissions Embraced

Trinity goes test-optional; number of first-generation students, Pell grant recipients, international students rises.

Embracing a Holistic Approach to Admissions

New Buildings for Arts and Science Open

Gruss Music Center and Crescent Center for Arts and Neuroscience open, supporting diverse fields in the liberal arts.

New Buildings for Arts and Science Open

‘Summit’ Strategic Plan Launches

Summit, a strategic plan for the future of Trinity, is introduced to guide College toward Bicentennial and beyond.

The ‘Summit’ Strategic Plan

Relationships in Hartford Enhanced

Trinity opens in downtown’s Constitution Plaza, with Liberal Arts Action Lab; introduces Center for Hartford Engagement and Research.

Enhancing Relationships in Hartford

Trinity Names Vice President for DEI

Anita Davis is hired in the new role of vice president for diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Trinity’s Inaugural Vice President for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Innovative Partnerships Begin

Trinity launches partnership with tech giant Infosys, becomes founding partner of med-tech accelerator, opens Innovation Center downtown.

Innovative Partnerships

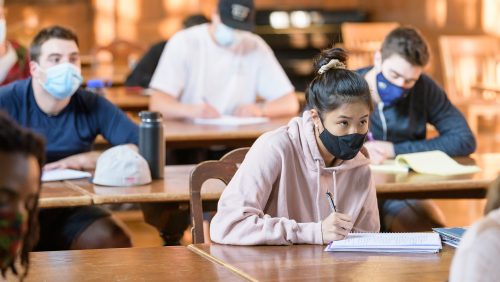

COVID-19 Years Present Challenges

Community members support one another through pandemic as Trinity, the world adapt to new ways of living, learning.

Trinity Community Persists through COVID-19 Pandemic

Actions Aim for Racial Justice

Task force produces Action Plan for Racial Justice, project studies history with slavery, group considers names of facilities.

Actions Aim for Racial Justice

College Works toward Sustainability

With leadership of new sustainability coordinator, Trinity builds on foundation of past projects, efforts to support sustainability.

Sustainability Action Plan

Trinity Plus Curriculum Launches

Credit-bearing co-curricular experiences, wellness program introduced; new Center for Entrepreneurship supports experiential learning.

The Trinity Plus Curriculum

Trinity at 200

Yearlong Bicentennial celebration kicks off with festival, Charter Day celebrations on campus and around the world.

Please visit the Trinity College Digital Repository and Encyclopedia Trinitiana, where many of the details and photographs included in the timeline are stored.