Research Blog

Trinity’s Center for Caribbean Studies supports research projects by students, faculty, and staff related to / based in the Caribbean region through grants and fellowships. Starting in AY 2023-2024, such grants will be followed by a blog.

Anthropology major Kathy Miranda (Class of 2024) offers our inaugural blog submission on her spring break fieldwork in Honduras.

All photos were taken by the author.

Hello everyone! My name is Kathy Miranda. I’m currently a senior studying anthropology on a pre-medical track with interests in health education and public health policy.

As I was thinking about possible topics of research for my honors thesis in spring 2023, I reflected on my experiences as a Honduran and a college student that had led to my personal commitments in how health, illness, and disease are understood, experienced, and informed by cultural, socioeconomic, sociopolitical, religious, and historical influences.

The global pandemic, COVID-19, immediately came to my mind as I observed the ways in which my Honduran family—both extended and immediate—behaved and responded to vaccine mandates, medical information, and restrictions. I noticed a general pattern of distrust, hesitancy, or complete negation. I began to consider the possible sources of their medical knowledge and the range of factors that might impact their medical decision-making. This led me to a larger curiosity of how power and gender manifests within Latino homes, specifically in Honduran homes where religion and patriarchy can historically be major players.

To offer some context, during the height of the pandemic, it was most often my female family members conducting and maintaining contact with family as well as, obtaining and disseminating medical information and remedies to other female family members whereas my male family members were virtually left out of these exchanges. Such interactions reminded me of a saying commonly used to explain the gender performance and the distribution of social roles within Latino culture which states, “Las mujeres son de la casa y los hombre son de la calle” meaning, “Women are from the home (belong to the home) and men are from the street (belong to the street). In other words, women traditionally are thought to govern the realm of domesticity and private spaces: the home and those living within the home while men govern public spaces. In context of medical anthropology, the mother then emerges as a major source of influence in the home extending so much so over even the medical decision-making of her adult children.

With this, I explored the infrastructures of honor, faith, and tradition that upholds and sustains Honduran culture and society.

Mothers might direct not only the decision-making but also the bodily autonomy, and identities of their children. Such intergenerational ritualized behavior is often explained through phrases like “that’s the way it’s always been”. This sacrifice of self can be understood as an exchange of reciprocity, I argue—the mother is expected to sacrifice herself for her children with her children as her life and they in turn recognize this sacrifice and exchange the devotion that they saw modeled to them as children.

A phrase that stuck with me from one of my interviews was, “Siempre, cuando considero y tomo una decisión, pienso en cómo se reflejará en mis padres; nunca escuchas que fulano hizo tal y tal; no, siempre es, ‘escuchastes que hizo el hijo de fulano’” meaning, “Always, when considering and making a decision I think about how it will reflect on my parents—it’s never, did you hear so and so did this—no, it’s always so and so’s kid did this.” Family connections are inescapable.

Faith could also be a powerful influence. While, in Honduras for fieldwork, I visited a public hospital in which I conducted interviews with medical personnel who described situations in which a patient—usually female—would deny any medical intervention—interpreted as a fear-informed decision by medical staff—out of belief that God would intervene and provide divine healing. Here, one’s agency could be displaced by faith in the process of a patient understanding a medical diagnosis and accepting recommended medical intervention and treatment.

Women, as both patients and caregivers often relied on faith and folk healing in lieu of Western biomedicine. This was often the case when there were gaps in their knowledge and understanding of a prognosis, diagnosis, treatment, or prescription— especially when women felt disregarded by their medical team.

My ethnographic informants evidenced the ways in which Honduran women might act from a standpoint of suspicion as a protective measure of survival in moments of crisis. Many of my female participants believed their well-being and safety could only be ensured by hypervigilance and alternative practice. Their beliefs permeated in both their own medical decision and their influence on those closest to them in the home.

Though beyond the scope of this blog, individual suspicion of Western biomedical practices arises in response to broader forces of political instability, corruption, impunity, and structural violence in Honduras. Health is often weaponized as a political tool. As one informant commented, “An uneducated population and a sick population is easier to control.”

To conclude, in Honduras, female power exists as a dominant influence in the home over generations and over the bodies and minds of their children. Influence is upheld by tradition, honor, and faith and materialized beyond the home during medical decision-making.

Hartford & Beyond: Hip Hop’s Caribbean Roots/Routes

In this blog post, Cole Alleyne (Class of 2027) reflects on his personal motivations and experiences connected to his CCS grant-supported project, “Rapping, Roots, and Reggae: Celebrating Culture Through Community.” His research interests find their origins in his upbringing in a West Indian household and the Trinity course, “Global Hip Hop Cultures” with Professor Seth Markle. Cole conducted ethnographic fieldwork as part of his work organizing Hip Hop salon gatherings in Hartford.

The crisp summer air brushes my face as I prepare for a transition. Grinning with excitement as, unbeknownst to the crowd, the sweet, sun kissed vocals of the Jamaican artist Sean Paul are about to get a warm American welcome from the hardcore drums of rapper Busta Rhymes. The acapella cues. I have to time it right. 3, 2, 1. Boom. The crowd starts to clap and move to this unexpected musical combination they have probably never experienced before. It’s at this moment, under the dimly lit streetlights, where the trials and tribulations of people’s everyday lives are temporarily tucked away that we get to see the city anew in, to me, its most ethereal glow.

Hartford is a city that without a doubt, lives and breathes hip-hop. A nearly 2-hour drive from the Bronx housing project that was the birthplace of this storied art form, Hartford, along with other Connecticut cities like Bridgeport and New Haven, were among the first urban areas, outside of New York, to catch the “Hip Hop fever.” Pre-internet, the name of the game was by word of mouth with people pooling whatever they had to come together in the productive community space of the block party. A congregation of Caribbean diasporic energy, artistic invention and community commitment, the block party is a cherished “third space” that served as the launching pad for many emerging creators who simply showed up with their best mix and kicks to show that their skills reigned supreme. Whether it was MCs on the mic or breakers on the cardboard, the block party became a cultural dojo in which there was no need for a sensei, only a mutual understanding of the importance of pushing the game forward.

When I first considered how I might contribute to this historical convention of shared wisdom and passion for an ever-evolving artform in Hartford, I was motivated by the level of community interest in and desire for the space of the block party. My research in Urban Studies brought me to not only establish new connections with the Hartford Hip Hop community but to expand my personal definitions of Hip Hop and its relationship to the Caribbean community.

What was initially envisioned as a series of four educational events has now evolved into a larger, sustained project that is working to bring educators, local entrepreneurs, creatives, and most importantly, the youth of the Greater Hartford region together to engage with Hip Hop as a practice of space-building and knowledge production.

As a local kid who always had a love for the art of the DJ, I grew up listening to the likes of Jamaican artist, Ragashanti and others on local West Indian radio stations. I always knew that there was a deeper connection between my cultural heritage and America’s number one cultural export: hip-hop. Yet, as I matured into my college years, I observed that there seemed to be a popular disconnection from the traditional and holistic approach to hip-hop that inspired many original Caribbean pioneers to fall in love with the genre. I became interested in recreating the space where Hip Hop culture was born by rejoining its elements: breaking, rapping, the DJ, beatboxing, and graffiti in contemporary urban practice.

Initially, it was challenging to get college-aged young adults to share in my enthusiasm as the salon spaces that I was proposing were the opposite of the typical strobe-light scenes more commonly associated with commercial rap that dominates the airwaves today. However, through my own grunt work and regular conversations, as well as utilizing my small but mighty following as a DJ, I began to see people pop out to the parties with a desire to obtain arguably the most crucial element of hip-hop: knowledge. Through the connections predicated on my ethnographic research, I was able to connect these individuals with Hip Hop professionals, who have channeled their love of the art form into becoming Hip Hop educators. Of these people, I found that almost all of them were of Caribbean descent, highlighting how this now very Americanized medium can be acknowledged as a mode to reconnect the second and third generations of Caribbean Americans to some of the genre’s pioneers. By the time September hit, community members old and young were eager to see a continuation of this work, and with the help of Trinity professors as well as a variety of local leaders, I am excited to say that these Hip Hop salons will be continuing in downtown Hartford, furthering the opportunity for me to do more ethnographic research and continue creating spaces for Hip Hop to positively impact future generations.

THE HIP HOP SALON: a communal art experience in downtown hartford

By Prof. Seth Markle (History and International Studies)

Salons are far more than places to get your hair done—they serve as community centers where stories, ideas, and support are shared, fostering connections across generations. For many, especially in Black and immigrant communities, salons preserve cultural traditions while offering a creative space for self-expression and identity affirmation. The Hip Hop Salon was created to reflect the salon experience by offering a monthly space for Hartford’s Hip Hop community to get together.

Co-sponsored by the Center for Caribbean Studies and the Trinity Chapter of Temple of Hip Hop and held in downtown Hartford at the Trinity Innovation Center between October and December, The Hip Hop Salon was the brainchild of Hiram Cardona aka Hydro 8SIXTY, a Hartford MC and cultural organizer, and Cole Alleyne aka DJ C-Money ‘27, a Trinity student member of Temple of Hip Hop.

A Communal Space for Everyone

What made The Hip Hop Salon so unique was its inclusivity. It was not just for Hip hop aficionados or aspiring lyricists; it was for anyone who wanted to tap into the culture and the do-it-yourself ethos that birthed Hip Hop in the South Bronx fifty years ago.

Of course, the soul of the event was in its rap performances. Local artists such as Hydro 8SIXTY, RAPoet, The Life Giving MC Blessings Divine, Connecti1, Franchize Tha Multytalent, UGODDESS THE POET, Lord Cookz, DreGotTheBlues, Jarelle Kershaw, A. Marquise, Bryan Alfred, Belle, S Type, Action, Monz Finito, Storm Biggaveli, The Gifted Onez (Mz Kim, Jayden, Jayda & Noah), Klokwize, Tang $Sauce, Grimm D, Show Rock, Legume Green, Tru, Arahmis.Wav, Stoned Jones, Yung TurnUp, Isaiah Jeremiiah, Gov Mag, Renée, and Ant, graced the mic, delivering raw bars that ranged from deeply personal to powerfully political.

The Hip Hop Salon wasn’t just about performances. It was also a platform for independent entrepreneurs such as Melvin Sotot of 8ight6ixzer0, Nancy Walker, Kim Bridges, Feed the Sol, Energy 33 Packz, and others.They sold everything from streetwear to crystals to natural herbs to handmade jewelry, emphasizing the importance of supporting small, minority-owned businesses while at the same time turning The Hip Hop Salon into an economic ecosystem for the community.

Other highlights included a live podcasting show hosted by Machine Gun Poptart, a video game booth by Izzy, an arts and crafts table, and a chess board set up. And if you just wanted to sit back and listen, you could hear DJ Stealth, DJ Michelle Bee, and DJ C-Money playing a combination of classics and providing boom-bap instrumentals for B-Boys Brandon and Tang $auce. Or you had the option to head into another room to listen to some head noddin’ beats by producers such as GWhiz, Pat’em Down, Band Lord Ease, TwistDown, Finessso, Azuchi, Bashiri, Luis, Delisio, Yung D of Connecticut People Records, 2wo4our, Jayden & Noah THE GIFTED ONEZ, and 2wo4our.

“The Hip Hop Salon showed and proved that community members of all ages want, need and appreciate spaces where they can engage in hands-on Hip Hop programming! Proof of concept! We came in Peace, with Love, Unity, and Safely Having Fun, that’s why we Hip Hop!”

~ Hydro 8SIXTY

One standout moment came in November when the artist Klokwise featured his new music video. Another one happened at the December session when, at the end, everyone in attendance praised the organizing work of Cole, showering praise on a Trinity student from Hartford for helping to open a space for the community.

Why The Hip Hop Salon Matters

Events like The Hip Hop Salon are more than just gatherings—they are part of a broader cultural movement. It is a reminder of Hip Hop’s roots as a tool for building community, amplifying voices, and resisting isolation. At a time when everyday life can feel overwhelming and fragmented, this monthly event created a space where people from all backgrounds came together to celebrate creativity and connection.Whether you were an emcee, a gamer, a chess player, a dancer, a graffiti writer, a DJ, a producer, a small business owner or just someone looking for a positive vibe, The Hip Hop Salon had something for you.

Panel Discussion: Hartford Beyond: Hip Hop’s Caribbean Roots/Routes

By Prof. Seth Markle (History and International Studies)

On November 5, 2024, I organized a panel discussion exploring the meaning and significance of Caribbean history and culture to growth and development of Hip Hop music and culture in the city of Hartford, the United States, and the rest of the world. Scheduled during Hip Hop History Month, a national holiday, the conversation was held at Trinity Library in the 1823 Room and was meant to shine a spotlight on Hartford’s rich Hip Hop history, dating back to the early 1970s.

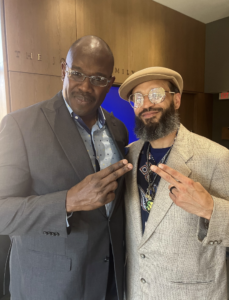

Brother X Lovejoy and Hydro 8SIXTY

About 40 students, faculty and staff attended, including students from the Trinity Chapter of Temple of Hip Hop, and from my courses “INTS 358: Global Seminar on Malcolm X” and “FYSM 138: Archiving Hip Hop”, got a chance to hear about a topic that is just beginning to gain national attention in academic discourse: the extent to which Caribbean culture and Caribbean diasporans contributed to the making of Hip Hop music and culture in the United States.

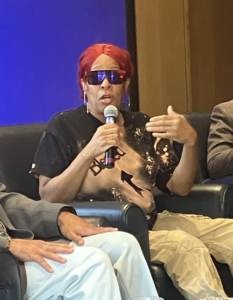

Hydro 8SIXTY

In tackling this question, I put together a panel consisting of Hartford community leaders who were born and bred on Hip Hop; who gravitated to the culture at a young age, and found a sense of purpose and identity in the face of extreme social and economic pressures. Moderated by Hiram “Hydro 8SIXTY” Cardona, a MC and cultural organizer, Brother X Lovejoy, Mz. Kim Bridges, Iran Nazarrio and June Archer shared their personal stories, reflecting on a Hartford of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s and what it meant to be Caribbean in Connecticut. Currently, these four Hartford residents are making their imprints as artists, authors, educators, life coaches, and community activists not only in Hartford, but in the greater New England Area.

It was really an honor to hear their stories and get to learn about a city I’ve been calling home for over 10 years.

Mz. Kim Bridges

Check out these responses from my students who attended:

“Hip Hop emerged as a powerful medium for cultural recognition among Caribbean and African American communities in places like Hartford. This helped tackle the divisions imposed in the area by white supremacy: as one panelist related, Boricua and Black tobacco-picking workers were deliberately separated from each other by foremen who wanted to divide and conquer.”

– Alex Cacciato ‘26

In this panel, one of the panelists talked about her experiences of being bullied and picked on in school, and how it led her to the powerful medium of hip-hop and writing. Her personal narrative is a testament to the deep connection between art and personal survival.”

– Nicole Ankrah ‘26

“When Mz. Kim (and the other panelists) spoke about all she did for the community, it reminded me of the importance of community support and collective action in activist spaces.”

– Claire Schrecengost ‘25

“Brother X Lovejoy focused on the relationship between hip hop and gang culture in Hartford, explaining how music and fashion were oftenused to assert identity within rival communities.”

-Ben Carley ‘27

“I found the panel to be very engaging as they discussed what it was like growing up in Hartford as a Puerto Rican, Jamaican, Dominican Republican, etc., and how these cultures might have alienated them at school but also how they were able to mesh these different cultures together and realize they are more alike than they seem.”

– Quinn McGlame ‘25

“Based on what I heard from the panel, once you really become a part of the Hip Hop scene—which isn’t very gate kept as Mz. Kim works so much with the youth, for example—the community has your back and will answer the phone, or make the call. People go out of their way to help their community members out.”

– Vivian Jacobs-Townsley ‘25

“It was interesting to see the tough background that the speakers came from and how they used the lessons they’ve learned to succeed in their respective areas. They’re trying to bring about some kind of positive change in underprivileged and black and brown communities. Although they’re going about it in different ways, the mutual understanding that we must help our fellow people is there.”

– Jarrell Okorougo ‘26

Iran Nazarrio

Following the Drum: The Gombey Tradition in Bermuda

Dorothea (Dora) Hast, Ph.D. (Ethnomusicology, Wesleyan University)

Visiting Scholar in Residence, Center for Caribbean Studies

Visiting Lecturer in Music (Fall 2024)

Warwick Gombeys, Bermuda, January 1, 2025

Gombey is an Afro-Bermudian street tradition that developed in colonial Bermuda more than two hundred years ago bringing enslaved people of West African, Caribbean and Native American heritage together during the Christmas season. These processions of masked dancers, musicians and followers are historically linked to Christmas traditions on other Caribbean islands colonized by the British, including St. Kitts, the Bahamas, Jamaica and Belize. While suppressed and often ridiculed by the colonial government well into the twentieth century, Gombey performers today are celebrated as national emblems.

I began researching the Gombey tradition while vacationing in Bermuda in 2018 with my husband, Stan Scott. As ethnomusicologists, we seek out local music performances and musicians whenever we travel. After seeing and hearing a Gombey group perform on the street in the capital city of Hamilton, we were intrigued by the drumming, dancing and intricate regalias. We stopped in at the Bermuda Government’s Department of Culture the next day to find out more about the tradition. At the end of our informal meeting with the staff, we were invited to attend an upcoming Gombey Festival. I flew to Bermuda that October to participate in the three-day event where I met our future collaborator Irwin Trott, the Director and lead drummer of the Warwick Gombeys and a passionate spokesperson for Gombey culture. We started correspondence and then met up again the following July at the Wampanoag Powwow in Mashpee, Massachusetts.

Warwick Gombey Dancer Ivan Trott in regalia: Ivan is Irwin’s brother and currently the oldest active dancer in Bermuda. Gombey regalia includes painted masks, high hats, intricately decorated and embroidered capes and several weapons. Here, Ivan is holding a bow and arrow. Bermuda, June 2023.

Warwick Gombey Dancer’s Cape, January 2025

At this time, Stan and I were both surprised to learn that the Gombey tradition has roots close to our home in Connecticut. The relationship began in the seventeenth century, which marked the rise of British emigration and its accompanying evil, the Atlantic slave trade that brought enslaved Africans, West Indians and Native Americans to Bermuda. Native peoples, including the Pequots from Connecticut, the Narragansetts from Rhode Island and the Wampanoags from Massachusetts, were enslaved and shipped from our region after the Pequot War (1636-38) and the King Phillips War (1675-76). A reconnection of Bermudians with their Native cousins took place three centuries later in 2002 when a delegation of members from these three tribal nations traveled to Bermuda. Since that initial reconnection, there has been a concerted effort to revive Native awareness in Bermuda and to encourage and promote travel and the sharing of cultural traditions at annual Powwows, both in New England and in Bermuda. Irwin has been a strong cultural advocate, bringing the Warwick Gombeys to many Powwows in Connecticut and Massachusetts over the years, including last year’s Schemitzun (Festival of Green Corn) hosted by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation (https://www.schemitzun.com/)

Warwick Gombey Drummers at the Mashantucket Pequot Schemitzun, Connecticut, August 2024

After attending the Mashpee Wampanoag Powwow in 2019 and conducting two more research trips to Bermuda before the pandemic, we became interested in working on a collaborative book project that would focus on the interplay of music and dance while examining issues of identity, resistance and nationalism over time. Stan and I were fortunate that Irwin wanted to partner with us. As a Gombey insider, he has directed his own troupe for the last twenty-eight years and been involved not only in training performers, but in educating and mentoring the young people who are in his troupe. He is an eloquent speaker with a deep understanding of the historical significance of the Gombeys, as well as their place in contemporary Bermuda.

Since our decision to work together, the three of us have documented and analyzed many performances and interviewed musicians, dancers, troupe leaders and regalia makers on the island, partly supported by the Bermuda Department of Cultural Affairs. We have focused both on contemporary performance venues and traditional contexts for Gombey performance: the street festivities that take place throughout Bermuda on December 26 (Boxing Day) and New Year’s Day. Unlike many events that are sponsored by the Government of Bermuda or hosted by local businesses, including wedding venues and hotels, the activities that take place on these days are not staged or promoted for tourists or party goers. Instead the processions and performances are spontaneous and improvisational in nature, including dancers, musicians and community members who are called out of their houses by the sound of the drums to follow their favorite Gombey groups. Troupe members are often fed along the way, and some still traverse the entirety of the island from sunrise to sunset. Rival troupes meet and sometimes engage in Gombey battles, competitions between dancers and drummers from each group.

Gombey group out on the street at night during the Christmas season, December 2022

My two collaborators: Irwin Trott and Stan Scott at the Society for Ethnomusicology Conference in Ottawa, Canada, October 2023

Warwick Gombeys, Boxing Day, December 2022

Making Echoes and Collisions

In this blog post, Lisa Lynch, Gallery Director and Organizing Curator for Widener Gallery, reflects on facilitating and organizing the art exhibition, Echoes and Collisions: The Art of Frantz Patrick Henry in Conversation with Selections from the Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, sponsored by the Center for Caribbean Studies and the Department of Fine Arts.

All photos courtesy of Pablo Delano.

Sometimes, after months of careful planning, research, and collaborating, a serendipitous event changes everything. One such moment occurred when Pablo Delano, Charles A. Dana Professor of Fine Arts, visited the studio of Frantz Patrick Henry at NXTHVN, an art incubator lab in New Haven.

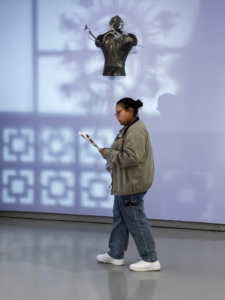

Exhibiting artist Frantz Patrick Henry with his exhibition, Echoes and Collisions, Widener Gallery

Pablo and I had been planning to co-curate an exhibition in Widener Gallery using work from Trinity’s Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, focusing on Vodou in Haitian art. Early in our planning, we had explored the possibility of pairing work from the collection with that of a contemporary Haitian artist, but unable to find an artist whose work seemed ideal for the project, we decided to focus solely on work from the collection. Certainly, a selection of work from the Graham Collection, which includes more than 300 paintings, sculptures, and objects, would have led to a compelling exploration into the rich Haitian cultural tradition.

When the exhibition checklist was nearly finalized, Pablo met Patrick, a Haitian-born artist living in Montreal who recently completed his MFA at Yale and is now completing an artist residency at NXTHVN. A multidisciplinary artist, Patrick explores the idea of “becoming” through sculpture, painting and installation. Pablo thought immediately that Patrick’s work would create the provocative pairing that had eluded us. He mentioned the exhibition to Patrick, returned to campus, and sought out my opinion.

I was thrilled. I had long wanted to organize an exhibition of contemporary art paired with historical objects. Since experiencing the exhibition Yankee Remix at MASS MoCA more than twenty years prior, I had been intrigued by the myriad ways that artists can use historical objects or places to recontextualize or expand upon their work, whether harmoniously connecting past and present or encapsulating dissonance and tension.

Patrick embraced the project with verve. He began by exploring the entire Graham Collection online, through the Trinity Digital Repository. From the hundreds of works of art gifted to Trinity College by Mrs. Graham’s children in memory of their mother, Patrick made a preliminary selection of 27 to view in person. Barbara Sternal, Art Collection Manager for the Watkinson Library, pulled the work from storage and arranged it for display. What a treat to see all this work in person – with its vivid colors, luminous surfaces, and loose or detailed brushwork – and to witness Patrick’s interaction with the work, as he studied each image, took notes, and asked questions.

Frantz Patrick Henry, Vestiges of Light, 2024, steel, cast iron, light, from Echoes and Collisions, Widener Gallery.

Patrick returned to his studio with colossal tasks: to make a final selection of work from the Graham Collection to exhibit in conversation with his own, to identify the concurrent or dissonant themes between his work and that from the collection, and to design a floor plan that encouraged dialogue between the work.

Pablo and I anticipated that Patrick would send us a checklist of work to be included in the exhibition, along with a floor plan outlining where each would hang, but he surpassed our expectations. His proposed plan included sculptural walls that would define and divide the gallery space, as well as act as a support for Serge Jolimeau’s sculpture, Zodiac. Another painting, Jean-Baptiste Bottex’s Walls of Jericho, would be exhibited within a custom-built frame mounted to the back of one of Patrick’s sculptures, Resurrection Highway – a motorcycle frame whose working parts have been replaced with sculptural elements, a surgery light, willow weaving, and a fabricated “lung” that “breathes” with assistance from an attached plywood box filled with a hospital pump, and from which medical tubing and electrical cords spilled.

Patrick’s proposed, unconventional installation methods filled us with excitement, but also apprehension. Would the fabricated wall be strong and steady enough to safely support Zodiac? Would Walls of Jericho be secure within the custom-designed frame? Would all materials that touch the art be archival?

We deferred to Barbara and Christina Bleyer, College Librarian, Associate Vice President of Libraries and Digital Learning, and Director of Special Collections and Archives for Watkinson Library, whose concerns echoed our own. Patrick answered our questions with increasingly detailed plans and sketches. Satisfied that the works of art would be safe, we approved his plans.

Despite Patrick’s detailed planning, the installation was a fluid and creative process. Over the span of a few weeks, Patrick essentially transformed Widener Gallery into a gallery-wide installation; his work and that from the collection was placed not only in conversation, but as parts to a cohesive whole.

Each day, Patrick added, subtracted, and manipulated components of the exhibition. He created new sculptures to add flora throughout the space, furthering the connection between each of the installation components. He removed a section of the wall’s smooth exterior façade to avoid a repetitive symmetry and reveal the structure beneath. He adjusted the motorcycle headlight and gallery lighting to allow the shadow from the light shining through Zodiac and the sculpted wall to frame another of his sculptures, Vestiges of Light, creating a new work comprised of light, shadow, cast iron, and steel.

Echoes and Collisions, Widener Gallery, Installation View

Patrick created Echoes and Collisions with the aim to “pay tribute to Edith A. Graham’s legacy while embracing the unpredictability of cultural dialogue. In this space, art becomes a force that collides, challenges, and ultimately expands our understanding of heritage and possibility.”

The dialogue between Patrick’s work and that from the Graham Collection presents questions and provokes conversation about the meaning of cultural heritage and about our place in the present within the context of our pasts.

Exploring Environmental Policy and Governance in Bonaire: A J-Term Course Development Journey

By Professor Stefanie Chambers, Department of Political Science

With support from Trinity College’s Center for Caribbean Studies (CSS) and the Global Faculty Scholars Program, I have developed a J-Term course focusing on environmental policy and governance in Bonaire. CSS funding supported two exploratory trips to this Dutch special municipality in the southern Caribbean, providing essential groundwork for what will become a unique educational opportunity for Trinity students in January 2026 or 2027.

Dive site along coast of Bonaire. The entire island is surrounded by a protected marine park. Photo credit: Stefanie Chambers.

Why Bonaire?

Bonaire represents a compelling case study for examining the intersection of colonial relationships, environmental conservation, and governance. Bonaire exemplifies ongoing colonial connections in the Caribbean as a “special municipality” of the Netherlands alongside St. Eustatius and Saba. With approximately 24,000 residents, this small island boasts extraordinary ecological diversity that has shaped its political and economic development.

Bonaire is particularly interesting because the island is surrounded by the Bonaire National Marine Park, comprising over 6,000 acres. Additionally, 17% of the island’s land mass is designated as Washington Slagbaai National Park. Conservation efforts have been central to the island’s governance, with the establishment of the National Bonaire Marine Park dating back to 1979.

Bonaire stands at a crossroads, determining whether its future will prioritize environmental protection and eco-tourism or pivot toward casino gambling and international hotel chains. This tension makes a course on environmental policy and governance in Bonaire both timely and relevant for Trinity students interested in political science, environmental studies, and Caribbean politics.

Central to Bonaire’s political economy is its relationship with salt. Initially harvested by enslaved people, today it is produced by Cargill. Photo credit: Stefanie Chambers.

Research Trips: From Proposal to Course Development

My first exploratory visit in March 2024 allowed me to assess the feasibility of developing a J-Term course that would provide students with a rigorous examination of power dynamics, marginalized communities, corporate influences, and colonial relationships on the island. Given the scarcity of literature on Bonaire’s politics and ecological issues outside of tourism books, collecting primary sources and establishing connections with local stakeholders was essential.

During my visits, I connected with environmental organizations such as Wild Conservation, Science and Education, and Reef Renewal. I also explored the Donkey Sanctuary, Echo Dos Parrot Sanctuary, and the island’s unique mangrove ecosystem. These sites will serve as valuable field experience locations for students in the future course.

Course Design: Blending Virtual and Experiential Learning

The course I’m developing will combine two weeks of virtual learning with six days of intensive field experience on the island. During the online component, students will explore Bonaire’s political framework, conservation history, and current environmental challenges through readings, discussions, and virtual meetings with stakeholders.

The on-island portion will include:

- A guided snorkeling introduction at Buddy Dive to experience firsthand the marine ecosystems that have shaped Bonaire’s conservation policies (especially reef restoration efforts)

- Visits to key sites including the Mangrove Center, Donkey Sanctuary, and Echo Dos Parrot Sanctuary

- Meetings with conservation organizations like Reef Renewal

- Exploration of historical sites including the Slave Huts and Fort Oranje

- Discussions with local non-profit organizations and environmental advocates

Along the coast of Bonaire there are preserved slave huts. These were used as housing for enslaved people who worked the salt flats. Photo credit: Stefanie Chambers.

Beyond Tourism: A Critical Approach

While many visitors experience Bonaire primarily as tourists, this course aims to move beyond superficial engagement by examining the complex political relationships that shape environmental policy. Students will analyze how Bonaire’s status as a Dutch public entity influences its governance structures, resource management, and conservation strategies.

The course will contextualize Bonaire’s experience within broader conversations about decolonization, sovereignty, and environmental justice in the Caribbean. By framing the political and economic position of Bonaire within the history of colonial domination and regional environmental policy, students will gain a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing small island states.

Looking Forward

As I finalize the course design and work with the Office of Study Away to identify financial aid for students, I continue to explore potential partnerships with colleagues across Trinity’s campus, including those in History, International Studies, Environmental Studies, Economics, and Urban Studies. I’m particularly excited about the possibility of a co-teaching arrangement that would bring interdisciplinary perspectives to this complex topic.

This research and course development was made possible through funding from Trinity College’s Center for Caribbean Studies and the Global Faculty Scholars Program.

Professor Stefanie Chambers is a faculty member in the Department of Political Science at Trinity College. Her research interests include urban politics, race and ethnicity, and environmental policy.

The Creation of the Djab: Haitainness on the Island and in America

By Abigail Robert (Class of 2025)

All photos are courtesy of the author.

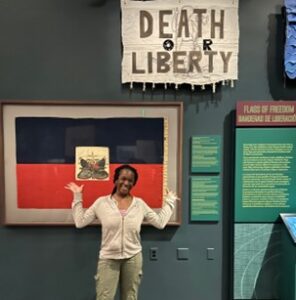

Through the support of Trinity’s Center for Caribbean Studies, I was able to travel this spring to Washington, D.C and Miami, Florida for research for my senior thesis. My project entitled, “The Creation of the Djab: Haitianness on the Island and in America” focuses on how American misrepresentations of Vodou have contributed to the legacies of colonialism and anti–Blackness in the afterlife of slavery. In particular, I use Haitian epistemology to analyze how Haitians have been characterized as “djab” as harmful, demonic, chaotic, and in need of control. In both research locations, I had the opportunity to visit museums, cultural centers, and to interact with the Haitian diaspora.

I began my travels in Washington D.C, where I was able to visit historic Black sites such as Howard University and the Museum of African American Heritage and Culture. I conducted an interview with Marvens Belidor, the president of the Haitian Student Association, to further understand how Haitians are organizing in the United States and what kinds of necessary conversations are being had amongst Haitian youth. At the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall, I observed the historical representation of Blackness in America starting with the Transatlantic slave trade and ending with the cultural contributions of Black Americans today. In my second research stop in Miami, Florida I spent a significant amount of time in the Little Haiti community. Florida is home to the largest Haitian diaspora, and there I got to engage with Haitian professionals, including manbo — Vodou priestesses, academic professors, chefs, and local business owners. To experience Little Haiti was an enriching moment that has allowed my research to be more grounded, as well as cultivated much of my lived understanding of the content of my thesis chapters.

I also had the opportunity to meet with Laider Andre, who has been serving the community through his Botanica for over 28 years. He has been in Miami since the rise of anti-Black discourse amongst Haitian and African Americans and is a witness to the gentrification that Little Haiti is currently experiencing. Additionally, I interviewed Jerry Jerome, who is a Haitian storyteller and communicator. In his personal work, he speaks on social media to an audience of around 40,000 people discussing Pan Africanism and analyzing the dynamics of race and Anti–Blackness in America and abroad. When travelling to Fort Lauderdale, I had an exchange with manbo Esther Charles. As a Cap Haïtien native, Esther communicated with me how Vodou is understood from the perspective of a practitioner, and how she articulates the origins of common American misconceptions. Vodou, in her words, has become an imagined religion that has been disrupted through fear, exoticism, and romanticism. However, its roots transcend, and it continues to be a source of liberation for Haitians.

From Brooklyn to Queens, Lastly, I spent time in boroughs across New York reconnecting with family and introducing myself as well as this project to interviewees. I had the privilege to interview Dr. Pierre Louis, who is a current professor and department chair of political science at CUNY Queens College and a former member of President Jean Betrand Aristide’s cabinet, to understand how he understands democracy as an imagined phenomena in the United States as it was never afforded to Haitians. I reconnected with my cousin, Christa Dorvil, and unpacked how she observes Haitianness and the demonic label to not only be intertwined with, but a gross misrepresentation of Black personhood in America. Beyond my research trips and interviews, through the support of the Center for Caribbean Studies, I was additionally able to purchase supplies to begin a creative take on this project, creating Claymation figures for the introduction and using editing apps such as iMovie, Canva, and Splice to create transitions, and create an environment that excites the viewer throughout the duration of the documentary.

This project could not have been completed without the assistance of Professors Guzmán and Euraque. Thank you again to the Center of Caribbean Studies!

To learn more about the documentary component of my project: please see link below:

https://youtu.be/JosEgMrbRDc?si=0b7irOkNJhvAX54r

Walking the Fragments: Visual Sidewalk Stories from Ciudad del Este, Paraguay

By Alex Goiris (Class of 2026)

Synopsis: This project combines visual analysis and interviews to explore how fragmented sidewalks shape the daily lives of pedestrians in Paraguay. By studying different street types, the research highlights physical gaps and accessibility issues as well as psychological and social impacts of fragmentation. The findings reveal both challenges and opportunities for creating more inclusive and engaging urban environments.

I was drawn to create an interdisciplinary study between the visual analysis of fragmented sidewalks and the psychological impacts on pedestrian life in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay. Most times, many people do not think of sidewalks as research opportunities, but to me, they are essential spaces for everyday life. My goal was to understand not only how sidewalks look and function, but also how residents feel while using them.

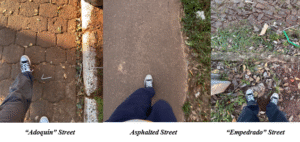

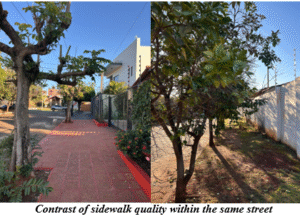

To begin with the process, I read articles on urban walkability and environmental psychology, as well as listening to podcasts and watching videos that explored how urban design shapes daily experiences. Then, I spent a month in Ciudad del Este walking its streets, observing, and collecting evidence. I documented sidewalks through photographs, video clips, and timelapses. To organize my analysis, I created a simple 3-point scale (poor, average, good) and applied it to a series of measuring factors across the city’s sidewalks. I selected three different urban contexts: First, asphalted streets in high-mobility areas, usually downtown and main avenues. Second, “adoquín” streets in areas (formally planned residential neighborhoods). And lastly, “empedrado” streets (uneven stone paving) in outer neighborhoods (often with little to no formal planning).

The selection of streets were randomised. However, I selected 2 streets per urban context. On each street, I analyzed both sides over at least two blocks, giving a more balanced picture of how fragmentation looks within the city. Alongside this visual work, I conducted four in-depth interviews with residents who regularly walk and who do not own cars. I recruited them through an online flyer, asking about their everyday use of sidewalks.

After these processes, I discovered something more complex than I expected. Residents consistently described planned residential areas as having the “best” sidewalks among other areas. Yet, my block-by-block analysis rated those same sidewalks only as “average” with extreme fragmentation even within the same street. A single block could sections that were smooth and functional as well as others that were broken, obstructed, and even poorly maintained. As another resident noted: “Some sidewalks are just horrible, you’ll stain your shoes because there’s water everywhere from the broken pipes, or trip on loose stones and fall. It’s a disaster.”

In contrast, asphalted streets (including downtown areas) with high-mobility and outer empedrado residential neighborhoods were rated as poor quality across most blocks. Another problem to be highlighted is that accessibility measures were almost absent everywhere, meaning there were zero ramps or other inclusive design elements present.

The interviews revealed that most residents use sidewalks mainly for commuting rather than for enjoyment of their surroundings. Residents mentioned avoiding walking at night as well as sidewalks being treated as extensions of private property, such as for business displays, decorations, or even car parking. Some residents even mentioned: “In Paraguay, we don’t feel like we are part of public spaces, and that’s also because these spaces are not really prepared to be public.” This contributed to the feeling that sidewalks were not truly public spaces for lingering or collective use.

Overall, this research project highlighted the value of combining psychology and urban studies, two fields whose intersection sometimes is overlooked. Bringing them together allowed me to see sidewalks not only as a physical infrastructure but also as spaces that constantly shape people’s emotions, behaviors and sense of belonging in the city. The findings suggest the need for stronger regulation and accessibility while also raising community awareness that sidewalks are shared public spaces, not private extensions. Although homeowners have the right to use sidewalks in front of their properties, they also share the duty to maintain and keep them accessible, and care for them as part of the city’s public treasure. So, small as they may seem, sidewalks tell powerful stories about how cities function. In Ciudad del Este, that story is highlighted through fragmentation but also as an opportunity to create more inclusive and engaging urban environments that truly invite people to walk.

Liberation Through Sound: A Journey Through Caribbean Anti-Colonial Resistance

By Isabella Zohreh (Class of 2026)

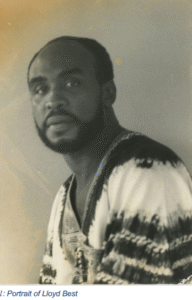

I was first introduced to Trinidadian philosopher Lloyd Best’s concept of the “Greater Caribbean” during a guest lecture by Dario Euraque, William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of History and International Studies at Trinity. The lecture took place in my “Toca Brasil!” class during the Spring 2025 semester, taught by my academic advisor, Eric Galm, Professor of Music. Both professors encouraged me to apply for the Maurice Wade Student Fellowship in Caribbean Anti-Colonial Thought, which awarded me the opportunity to work with Maurice Wade, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy. I specifically chose this fellowship because I’m highly interested in the intersection between music and philosophy, specifically anti-colonial philosophy and theories of human connection.

International Studies at Trinity. The lecture took place in my “Toca Brasil!” class during the Spring 2025 semester, taught by my academic advisor, Eric Galm, Professor of Music. Both professors encouraged me to apply for the Maurice Wade Student Fellowship in Caribbean Anti-Colonial Thought, which awarded me the opportunity to work with Maurice Wade, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy. I specifically chose this fellowship because I’m highly interested in the intersection between music and philosophy, specifically anti-colonial philosophy and theories of human connection.

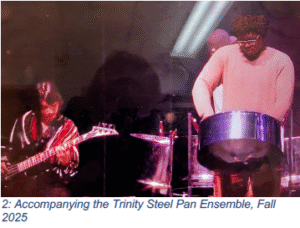

My love of the music of the Greater Caribbean began at a very early age. My father is Cuban and grew up in Puerto Rico, and I grew up with Celia Cruz, Tito Puente, and Ray Barretto playing at full volume from my mother’s boombox. As I got older and started to study music and ethnomusicology, my background in the Caribbean informed much of my academic trajectory. I began to serve as a teaching assistant for Trinity’s Steel Pan Ensemble, and have spent the bulk 1: Portrait of Lloyd Best of my Monday and Wednesday nights since surrounded by bright, resonant instruments that were quite literally forged from colonial refuse. I’ve always felt there was something profound about these instruments, something that went beyond their technical brilliance or their beautiful sound. But it wasn’t until I started meeting weekly with Professor Wade and digging into the archival materials at the Lloyd Best Institute that I began to understand that the steel pan, and music and art more broadly, were forms of anti-colonial resistance in and of themselves.

Through this fellowship, I set out to examine how all music, not just explicit protest music, can be thought of as a forms of anti-colonial resistance in the Greater Caribbean, with a focus on Trinidadian music (steel pan and calypso). I was particularly interested in understanding how music and the act of music making allowed communities to claim and retain cultural agency in both the face and wake of oppression This research was deeply personal—a way to academically engage with the musical traditions that have shaped my own identity.

My methods were fairly straightforward but quite effective, and rather enjoyable as well. I worked through digitized materials in the Lloyd Best Institute’s online archives held at Trinity, examining historical newspapers and documents about steel pan and calypso, papers and videos from Best, and archival photos, all while having ongoing conversations with Professor Wade. He introduced me to Best’s philosophical frameworks, helping me understand theories and see connections I might have otherwise missed. I also read through Prof. Wade’s Substack on Best quite a bit, which provided necessary and helpful context to some of Best’s more complex work.

My first breakthrough came when Professor Wade introduced me to Best’s idea of “epistemic sovereignty.” This principle allows a community to be recognized as they choose to be, not how others and their preconceptions may see them. It’s a philosophical framework that explains how colonized peoples could produce knowledge and assert their own narratives even when formal political institutions excluded them, as opposed to being reduced to the opinion of someone outside the community. When British colonial authorities banned skinned drums in late nineteenth-century Trinidad, they weren’t just prohibiting instruments—they were attempting to control consciousness itself, to prevent the kind of organizing and communication that music enables. But Trinidadians adapted. Bamboo stamping tubes, biscuit tins, and finally those discarded oil drums became vehicles for what Best called “native intuition”—a region’s instinctive ability to generate new forms of expression from within its own experience.

As an established student of ethnomusicology (the study of music and culture), I had the tools to understand music technically, but it was this archival work that showed me how music functions as a form of thought itself, how rhythm and melody can carry ideas that formal discourse cannot contain. Calypso emerged as “the people’s newspaper” precisely because the plantation system had narrowed legitimate political participation. When newspapers wouldn’t print certain stories, and politicians wouldn’t address certain grievances, calypsonians did. Calypso songs are a form of cultural analysis, offering sharp critiques of colonial power and becoming spaces of working-class political education.

Working through the digital archives and with Professor Wade while serving as a TA for the Steel Pan Ensemble created this productive loop between theory and practice. In the ensemble, I wasn’t just helping students learn technique; I was also exposing them to an incredibly important piece of anticolonial history. Every rehearsal became a continuation of the work that Trinidadian communities began when they first struck those oil drums and heard music ring out.

Working through the digital archives and with Professor Wade while serving as a TA for the Steel Pan Ensemble created this productive loop between theory and practice. In the ensemble, I wasn’t just helping students learn technique; I was also exposing them to an incredibly important piece of anticolonial history. Every rehearsal became a continuation of the work that Trinidadian communities began when they first struck those oil drums and heard music ring out.

This research has expanded my understanding of what counts as anti-colonial thought. Sometimes it sounds like a steel pan or a calypso song, sometimes it’s a painting or a theater performance, sometimes it’s a groundbreaking work of postcolonial thought. The fellowship didn’t just teach me about colonial history; it allowed me to understand how creativity itself becomes a form of freedom, how marginalized communities use art to contest power and claim space on their own terms. It allowed me to hear liberation in the music I already loved.

Photo 1 comes from the Lloyd Best Institute of the Caribbean archives

Photo 2 was pulled from a video of the Trinity Steel Pan Ensemble performing in Fall 2025, recorded by Sean Donnelly

Crossroads of Care

By Ella Samson (Class of 2026)

Hello, I am Ella Samson. I am a senior at Trinity studying anthropology. Within anthropology, I am particularly interested in religions, African diasporic religions, and healing and liberation within these different practices. I was raised in West Hartford, Connecticut. Half of my family comes from New York, by way of Haiti, and the other half comes from rural Michigan.

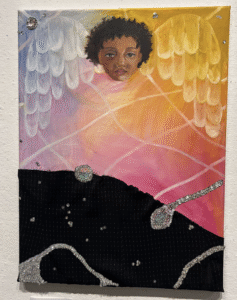

Ella Samson, Angels Pt. 1, 2025

My research project under the Center for Caribbean Studies started with my family. My dad has told me about an ancestor, his grandmother, Odette Laforest, since I was a child. He describes her fiery personality and her fierce love for him. Among so many other things, he has also relayed tales of her life as a Vodouisant, a practitioner of Haitian Vodou. In his estimation, Vodou was a stabilizing force for my great-grandmother. This has always transfixed me. I have wondered what her life was like and what her experience of her religion and practice was. I ask, how did Vodou help my Great-grandmother?

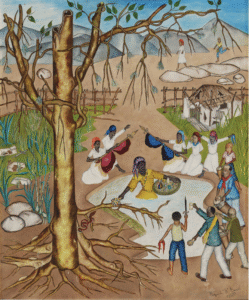

Benoit Rigaud, Cérémonie sous le Mapou, 1971

My second inspiration has been my personal experience of Bipolar disorder and spiritual psychosis. In the past, before psychiatric and spiritual treatment, I struggled with experiencing states of horror and utter confusion. Knowing those states, I am creating an engaging repository of knowledge for people in any way related to mental health issues and care, Haitian Vodou, and all other relevant altered states of mind or being. I am creating a resource that I believe could have helped me, as well as the kind of practitioners and care providers who did help me.

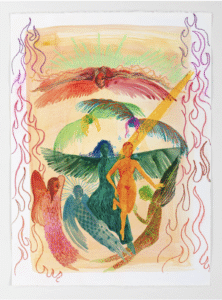

Naudline Pierre, 2019, Purified by Fire

My third and final inspiration is the work of anthropologists such as Tanya Luhrmann and Karen McCarthy Brown, who write about the ways mental illness presents itself differently in different cultural contexts, and the ways Vodou is used to heal, respectively. The work of these two women both get at something that I wish to explore: the difference that Vodou, as a non-Western religion, brings to mental illness as it is understood in Western psychology, as well as the healing that comes out of their meeting.

My project is called “Crossroads of Care” because it deals with the intersection of two modalities of healing that have complex, fraught relations and highlights the ways that care emerges from this intersection. “Crossroads of Care” is centered around a set of ten Oral History semi-structured interviews with self-identified Vodouisants with proximity to mental illness. That means people who, in some way, incorporate Haitian Vodou in their lives, and have a history of mental illness, current mental illness, or treatment of clients with mental illness. The interviewees came from a wide range of backgrounds within the United States and Canada. I found participants online by posting a flyer to various online Vodou communities Assongwe and Makout lineages are represented in this study. Participants had different levels of involvement with and ranking in their Vodou practices, from clients to servitors and Manbos or Hougans (priestesses or priests).

Through this interview process, many topics emerged. Importantly, almost unanimously, the participants in this study voiced their desire for the study to help challenge and combat the stigma that plagues Haitian Vodou and its healing potential. I focus on that work in my writing. Stigma against Vodou is pervasive, beginning with its inception during the French chattel slavery of Saint Domingue, continuing with the creation of myths like Vodou cannibalism, and going on today with issues like the scapegoating of Vodouisants in the wake of the 2010 earthquake. To work against this, I focus on the true present of Vodou practiced in the West as a powerful and helpful alternative healing resource.

Hector Hyppolite, Damballah La Flambeau, 1946-48

The delineation between mental and spiritual problems, and a Vodou practitioner’s ability to properly diagnose both, was an important starting point in the understanding I gleaned from the interviews. In general, such distinctions between the different elements of a person’s experience of altered states (states differing from baseline experiences), came up in different definitions and descriptions of exposures to altered states by the participants. For example, when it comes to treatment, for the participants, treatment of mental disorder consisted of therapy, medication, and involvement with Vodou, serving the Lwa and Ancestors, and once again, there were boundaries between aspects. Some participants experienced what they described as mental illness symptoms that were unrelated to and not effectively treated by Vodou alone. Others experienced those described mental illness symptoms and resolved them through Vodou. Yet others experienced a mix. I describe the nuances and specific examples of this in my paper.

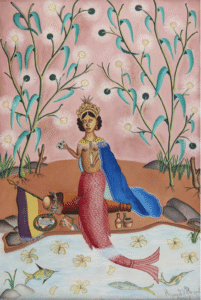

Benoit Rigaud, Untitled (La Sirene), 1955

Overall, this project has proved fruitful with the great number of stories related to altered states, mental health, and Haitian Vodou it has preserved. The dissemination of those stories will look like the sharing of a paper displaying the work of the project. It will also look like the production and sharing of an animated video that tells the narrative of the paper. The video aims to make a wider reach. I thank the project participants and mentor, my advisor Professor Landry, and the Trinity Center for Caribbean Studies for their contributions to this project.