The Benefits of Guaranteed Basic Income: Lessons from Advocates

Community Learning Research Fellow Abby Nick ‘24,

with Community Partner Maddie Granato, Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Advocacy Fund

and Faculty Sponsor Professor Chambers

Spring 2022, Trinity College, Hartford CT

Introduction

A. Research Question

Dozens of US cities, including Hartford, Connecticut, have begun to experiment with Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI) programs as a solution to generational poverty and racial inequality. Most GBI programs operate by giving citizens monthly cash payments with no strings attached to spend as they see fit. This cash flow helps recipients meet basic living costs, increase opportunities, and better their quality of life. The Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Advocacy Fund (CWEALF) is focusing on GBI programs because they help create an equitable society for all, especially the underserved or marginalized. CWEALF hopes to advocate for statewide GBI programs to combat the high levels of income inequality and racial poverty that exist throughout Connecticut. CWEALF invited me to partner with them to answer two research questions: What lessons have advocates learned in similar settings that may help CWEALF with supporting similar programs in CT? What have recent initiatives for guaranteed or universal basic income in the US shown about the outcomes of women’s opportunity to accumulate wealth, improve family health, and reduce reliance on other governmental programs?

B. Why is it important?

This research is incredibly important as it will help CWEALF and citizens of Connecticut better understand the benefits of basic income programs and how best to advocate for them. Millions of Americans struggle every day to meet their basic life needs. Parents forfeit time with their children, people pick up second or third jobs, and some even refuse jobs that would push them into a certain bracket as they are reliant on other governmental programs. Cash is one of the most direct and effective ways to provide financial stability to those who are most in need. It offers the dignity and self-determination that other programs do not and allows citizens to take ownership of their own life and spending decisions. Years of research demonstrate that when given unrestricted payments, participants in UBI and GBI programs are able to pull themselves out of poverty and create economic stability for themselves and their families. The work CWEALF is doing is crucial to moving towards UBI programs in every state.

Background Information

A. What is CWEALF?

CWEALF stands for Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Advocacy Fund, a statewide non-profit organization based in downtown Hartford that advocates for and seeks to empower women. CWEALF has advanced women’s rights and opportunities in Connecticut since 1973. They focus on those who are underserved or marginalized and strive to create an equitable society for women and girls. As an advocacy organization, they are interested in becoming involved in the fight for basic income in order to help low-income women advance and thrive. CWEALF pursues GBI programs to give women the opportunity to gain financial independence and achieve gender and racial equity.

B. What is the Difference Between Universal Basic Income (UBI) & Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI)?

Universal Basic Income and Guaranteed Basic Income are both forms of basic income programs that aim to provide citizens with a sum of income every year, no strings attached. These programs believe that cash is one of the most direct and effective ways to provide financial stability to those who most need it. The difference between the programs is in the qualification for who receives the funding.

Universal Basic Income is a model where income is distributed universally meaning every citizen is given the same sum of money per month. UBI is unconditional, with no strings attached and no work or financial requirements, meaning the 1% and those in poverty receive the same cash (Pinto, 4).

Guaranteed Basic Income provides cash payments to specific, targeted communities of people. This system specifically targets inequality by giving the money to those who need it: people living below the poverty line, those with inconsistent or no income, and marginalized communities, specifically communities of color. In this system, people who don’t struggle to meet their basic needs do not receive cash payments (Pinto 3).

To put it simply, a guaranteed income program is a UBI with qualifications.

Lessons from GBI Advocates

In order to answer my first research question, my study focused on qualitative interviews with various advocates who are working diligently in the fight for basic income. I chose to interview two advocates involved in projects that are located in or near Connecticut in order to learn about the effect of GBI in Connecticut. In addition, I interviewed one national advocate in order to learn about the fight for GBI in the US more broadly and how best to advocate for a statewide approach. Below are four key lessons and patterns that emerged during my interviews.

A. Advocates warned against opponents’ use of coded racist language

A key theme throughout my interviews and research was that much of the opposition to basic income programs is rooted in racial and economic discrimination. Opponents disguise racist intents into common language in debates and discussions. Advocates explained that many opponents see GBI as a free giveaway, offering free income to those too lazy to work. David Grant, head of the Hartford GBI task force, explained the opposition Hartford faced from surrounding majority-white towns:

“Our surrounding sister cities and towns have residents that are absolutely against [GBI]. They see it as a free giveaway… And so there are these divides, these cultural divides that exist even in a state like Connecticut… I learned very quickly doing this work just how divided the community is on a program like GBI”

The biggest opposition to the basic income program is the shame wrongly associated with giving money. We as a society view these programs as handouts and instead as assistance in rectifying a broken and inequitable system. Madeline Neighly, the Director of Guaranteed Income at the Economic Security Project stated:

“I think honestly, the biggest opposition is one of narrative. It is a deeply held, deeply ingrained belief around pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. There are both spoken and undercurrents of gendered racism around who is deserving.” (Neighly)

Advocates then explained that this opposition is often racially charged and when advocating for GBI you must be wary of opponents using racist language, Neighly went on to say:

“And I think there are very key prime examples that people are much more aware of, like the welfare queen racist trope, but it’s much deeper than that. So there are dog whistles that are used, There are ways in which we’ve all been steeped in that culture, and it’s really hard to challenge that both externally and within ourselves… One should be able to live in dignity because of their existence, not because of their value in the labor market.”

When advocating for GBI and UBI programs we must be aware of this underlying bias within conversation and opposition strategies.

B. Advocates recommend that programs focus on achieving individual agency and personal choice

Advocates expressed that Guaranteed Income programs are more beneficial than other forms of assistance as they allow choice and freedom. Not restricting what recipients spend the cash on it allows them choice and control in their life and to do what’s best for them. Neighly stated:

“Guaranteed income allows for trust and choice and freedom, and individuals know best how to support themselves and their families, and that’s what guaranteed income allows, rather than having hoops to jump through bureaucratic inefficiencies and other challenges. This is trusting individuals and giving them the foundation on which they can build their lives.” (Neighly)

Grant continues this thought by saying the goal of GBI should be to create individual agencies and allow people to take charge of their own futures, a concept that other assistance programs do not achieve.

“If we can shift people away from other social safety net programs, like housing vouchers and other benefits, and give them an opportunity to be more independent and have more individual agency, we can start to break the cycle of generational poverty.” (Grant)

Finally, advocates explained that individual agency looks different for everyone. Some use the money to not work extra jobs, or be more involved in their child’s life, or save it for housing, or use it for transportation. No matter what their choice it’s important that this choice is theirs to make. Grant explains this stating:

“We want to know, did UBI provide you an opportunity to enhance your quality of life?… to some people, it could be, I didn’t have to work a third job to provide for my family because of UBI. For another person, it might be that I was able to go to night school to work towards my associate’s or to finish high school. For other people, it might be I was able to buy a car or I was able to move. I mean, it’s different for everyone. But ultimately, individual agencies are going to be our gauge for how successful this program was.” (Grant)

The success of GBI can be measured by noting the increase in individual agency and free choice that programs provide to participants.

C. Advocates discussed how the pandemic changed the dialogue around GBI

Multiple advocates discussed how the pandemic changed the conversation about Guaranteed Income. When the government sent out stimulus checks through the CARES Act many citizens began to change the way they viewed income assistance. Hannah Khan, Deputy Director of Research and Development at Providence City Hall commented:

“I also think a lot of it has to do with the pandemic and the moment that we are in… we saw the government send out three rounds of direct stimulus checks, then monthly child tax credit payments. And that really changed the conversation in ways that we could not have anticipated at the beginning of the process. People became much more comfortable very quickly with the idea of the government just sending people cash.”

There is no better time to advocate for GBI programs as the pandemic has changed the dialogue around GBI and UBI. This is due in part to the high levels of unemployment and the stimulus checks that occurred as a result of COVID-19.

D. Advocates explained Connecticut is the perfect demographic for this program

Connecticut is a state with major generational poverty, income inequality, and racial inequity. Especially in cities such as Hartford and New Haven, citizens are unable to meet their basic living costs. The majority of Hartford citizens have no form of transportation and work multiple jobs. Advocates urged that GBI would greatly benefit the state of Connecticut. David Grant explained that when he heard of programs such as GBI he immediately thought Hartford was the perfect demographic. He stated:

“We are an 86% minority community and over 40% of our residents don’t have access to transportation so there are a lot of barriers that exist in our community and so we really took a look at UBI as a model and tried to determine whether or not this might be something that would help break generational poverty that exists in the city of Hartford.”

Hannah Khan explained that the progress Hartford is looking to achieve is exactly what they are seeing as a result of the Providence program.

“What Providence is seeing is the impact on families’ engagement in their children’s education and the impact on civic engagement as a whole. If people have a little less worry or are struggling a little bit less to make ends meet, they’ll have more capacity to be engaged in civic life, in their community, and in their children’s education.”

Guaranteed basic income greatly reduces the need in communities and allows citizens to gain individual agency and make choices about their spending. By putting cash directly into people’s pockets we can combat income inequality and racial and generational poverty in the Connecticut area.

Recent Initiatives

Once I completed my background research on GBI and UBI, I began to answer my second research question by looking into various pilot programs taking place across the United States. I examined the structure of each program, the political strategy used to create the program, the political opposition, and the effect of the program on participants. The main four pilots I examined were located in Stockton, CA; Hartford, CT; Providence, RI; and Hudson, NY. These case studies were selected as they are comparable to Connecticut cities and therefore would be most helpful for Connecticut advocates who wish to understand the feasibility and effectiveness of GBI Programs. Providence and Hudson are both located within or near the New England area and are comparable to Hartford in size and demographics. All three of these cities have similar yearly median incomes ranging from 22,000 – to 25,000 USD. Furthermore, Providence and Hartford are both similar in population with Hartford having around 130,000 residents and Providence about 170,000. Stockton is a city with wide income inequality that diverges from the rest of California. This is comparable to both Hartford and New Haven, Connecticut because both of these cities are located in very wealthy states. In both cities, minorities account for the majority of the population; 56% of Stockton’s population is made of people of color while Hartford and New Haven have over 70% minorities.

Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED)

- Description of Program

- February 2019: former Mayor of Stockton, Michael D. Tubbs, launched the guaranteed income initiative.

- The program gave 125 Stockton Residents $500 per month for 24 months.

- The cash was unconditional with no strings attached and no work requirements

- Recipient Qualifications: over 18 years old, reside in Stockton and live in a neighborhood with a median income at or below $46,033.

- Goal: to combat inequality, income volatility, and poverty.

- Key Stakeholders: Economic Security Project, Michael Tubbs

- Research-Based Program Results

- As the first successful program in the United States SEED has had the most studies published on its results. SEED analyzed results by comparing their treatment group, those receiving the $500 a month, to the Control group, a group of 25 citizens not receiving any payment.

- Guaranteed income reduced income volatility or month-to-month income fluctuations that households face. Income volatility is the month-over-month variation in income. Less volatility in monthly income allowed families to stabilize and plan for the future. In the one-year findings of the SEED program, the treatment group showed 46.4% income volatility while the Comparison Group showed 67.5% (SEED Data Dashboard).

- Studies show that employment among participants increased over the course of the program. Participants cited that they were able to use the money for transportation and child care to make job advancement accessible. In February 2019, 28% of recipients had full-time employment. One year later, 40% of recipients were employed full-time. Therefore it can be concluded that unconditional cash enabled recipients to find full-time employment (SEED Key Findings)

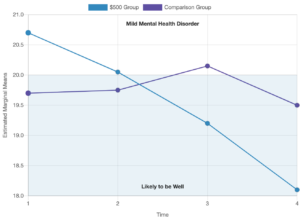

- Results show that the treatment group, those receiving the monthly payments, showed less depression and anxiety and enhanced wellbeing compared to the control group of residents not receiving the payments. This was studied using the Kessler 10 a survey and chart which measured “feelings of anxiety, like being fidgety or unable to rest, and feelings of depression, like hopelessness” (SEED Key Findings). Researchers concluded that recipients were healthier as a result of receiving GBI payments (SEED Data Dashboard).

-

- GBI alleviated financial scarcity creating new opportunities for self-determination, choice, goal-setting, and risk-taking. During 1-year follow-up interviews recipients expresses the feeling of control that GBI gave them as they were able to make individual choices and take charge of their lives. One participant quotes “I stayed in a bad marriage for longer than I should have because I didn’t have the funds or the means to leave” (SEED Key Findings). She was able to get out of the marriage due to the GBI funds.

Providence RI

- Description of Program

- Project run by Mayor Jorge O. Elorza

- Member of Mayors for Guaranteed Basic Income

- 110 randomly selected low-income people will receive $500 a month over the next year

- It is entirely philanthropically funded

- It received over 4000 applications for 110 spots

- First payments in the PVDGI Pilot went out on November 15th, 2021

- Recipient Qualifications: Providence residents with an income below 200% of the Federal Poverty level

- Research Groups: control group and treatment group

- Political Strategy: Privately funded so no need for political support

- Goal: To create trust and efficiency, eliminate costs associated with traditional welfare programs, and put those savings directly into the pockets of program participants.

- Key Stakeholders: Mayors for Guaranteed Income, Jack Dorsey Foundation, RI Foundation, Providence Community Relief Fund, Dorcas International

- Project run by Mayor Jorge O. Elorza

- How is this program different than others?

- Benefits Counseling

- The City of Providence and partners are taking a three-pronged approach to ensure that participants receiving other benefits are not harmed by receiving this guaranteed income.

- Research-Based Program Results

- The Providence program is still an ongoing process therefore no final report has been published. However, the program is now almost at the halfway point so interviews have been conducted. Participants reported in research interviews that they experienced a better quality of life. Participants stated they were using the money for transportation needs, buying their children Christmas presents, and giving their children a better life. One recipient said she was beginning to save for a down payment on a home so she can move her family out of project housing (providenceri.gov/mgi).

Hudson, NY

- Description of Program

- Project run by Mayor Kamal Johnson

- Member of Mayors for Guaranteed Basic Income

- 25 randomly selected low-income people will receive $500 a month for 5 years

- The program ran for 1 year already with 25 participants and is now adding 50 more recipients

- Recipient Qualifications: over the age of 18, live in the City of Hudson and earn under the city’s annual median income ($39,346)

- Goal: To benefit the Hudson community and demonstrate the power of basic income for all.

- Key Stakeholders: HudsonUP, The Spark of Hudson, Humanity Forward, MGI

- Project run by Mayor Kamal Johnson

- How is this program different than others?

- This program gives funds for 5 years while most pilots only run for 1 year

- Research-Based Program Results

- This gives research gave advocates a unique opportunity to study the longer-term effects of basic income on the trajectory of recipient lives as the program is a 5-year timeline as opposed to a 1 year. The current published research reports on preliminary outcomes for the recipient after the first year of the program. This research was conducted through interviews and online quantitative surveys (Hamilton 3).

- According to online surveys employment, both full-time and part-time grew from 29% to 63%. (Hamilton 3).

- In qualitative interviews, many participants noted that both their physical and mental health had improved since joining the program. In quantitative surveys, the percentage of psychological distress decreased significantly (Hamilton 7).

- As advocates predicted in the interviews above the majority of participants reported increased feelings of the individual agency during their interviews (Hamilton 7).

- Finally, recipients of the cash reported greater feelings of stability and security. As well as an improved ability to make plans for the future and family and community relationships. GBI allowed parents to spend more time with their children increasing their child’s development, test scores, and parent-child relations (Hamilton 15).

Hartford Pilot Program

- Description of Program

-

- March 2021: Hartford city council passed a resolution to form a GBI task force to develop the pilot. First Payments go out in June 2022.

- 25 randomly selected Participants will receive monthly payments of $500 for one year.

- Residents from all income levels are able to apply

- Recipient Qualifications: Single, Hartford Resident, U.S. citizens or green card holder, working at least part-time, primary caregiver to at least one child between third and eighth grade, or a formerly incarcerated citizen

- Research Groups: Active control group (25 citizens), Passive Control Group (25 citizens), Treatment Group (25 citizens

- Political Strategy: Organized community support first and then political support will come once they see the local support and need for such programs.

- Opposition to the program: The majority of opposition came from citizens of wealthy surrounding towns. Felt the program was a “free giveaway”.

- Goal: To enhance individual agency

- Key Stakeholders: Local non-profits, Hartford City Council Members: President Maly Rosado (Democrat), James Sanchez Jr ( Democrat), Marilyn Rossetti (Democrat), Wildaliz Bermudez (Working families Party)

- How is this program different than others?

- it is measuring physical and mental health throughout the study by collecting samples and measuring the hormone levels of participants.

- Open to people of all income levels

- Research & Progress

- The Hartford Pilot Program is going to be launched in June of 2022 and therefore there are no available results at this time. However, they have a research procedure set up and will be collecting results through quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. In addition, they will be testing participants’ mental well-being and hormone levels throughout the study through samples of hair and fingernails as well as physiological evaluations (Grant).

Counterarguments & Criticisms

Despite the evidence presented in this study, critics of GBI remain strong opponents to the implementation of programs on a broader scale. As noted above, opponents often see GBI as a government handout that contributes to laziness and frivolous spending. Furthermore, opponents claim that these programs will cause dependency and a lack of aspirations. However above all the main critique is that these programs are too costly, especially if they were to exist at a statewide or federal level.

During times of fiscal unpredictability, it is understandable that people would have concerns about increased government spending. However, as this study has demonstrated, the safety net of GBI has the potential to empower people, create opportunities to escape poverty, and maintain a basic standard of living. In addition, it increases spending and boosts the economy.

Critiques also fail to take into consideration the health benefits of GBI. As shown in the research coming out of pilot programs GBI decreases stress and anxiety and increased physical and mental health as well as overall well being, Furthermore, although not part of this project, many other studies have shown how GBI can help families, particularly young children from poor families, as the years progress. Families receiving GBI have shown increased test scores, better academic progression and increased brain development (Covert 7). In this sense, opponents could be missing the point of GBI in some of their criticism of the program.

Next Steps & Recommendation

After completing my research I have multiple recommendations for how CWEALF can become involved in the fight for GBI. To begin with, CWEALF should continue to track the progress of Pilot programs, particularly the Hartford Pilot to see how the community benefits and responds. Furthermore, I suggest partnering with other community non-profits. The majority of the pilot programs had multiple non-profits as key stakeholders. Non-profits can help gather financial aid and rally political support. Finally, I would suggest becoming involved with Mayors for Guaranteed Income. This organization alone has funded many pilot projects and serves as a national network of GBI supporters. This organization would provide endless resources to advocates.

In addition, I stress the impact of a statewide approach. Although local pilots are influential in the participants’ lives, the only way that basic income can make a lasting impact on the economic poverty and income inequality in the state of Connecticut is through state legislation and larger-scale programming. Therefore I believe that CWEALF’s efforts would be best used in advocating for statewide guaranteed basic income.

Conclusion

Guaranteed basic income greatly reduces the need in communities and allows citizens to gain individual agency and make choices about their spending. By putting cash directly into people’s pockets we can combat income inequality and racial and generational poverty in the Connecticut area.

Many lessons can be learned from both local and national basic income advocates that will help CWEALF advance similar programs. Advocates warned against opponents’ use of coded racist language explaining that much opposition to basic income programs is rooted in racial and economic discrimination. Furthermore, advocates recommend that programs focus on achieving individual agency and personal choice, a lesson proven in the research-based findings from various pilot programs. Recipients in three separate pilot programs reported increased individual agency and decision-making abilities. Finally, advocates urged that there is no better time to advocate for GBI programs as the pandemic has changed the dialogue around GBI and UBI. This is due in part to the high levels of unemployment and the stimulus checks that occurred as a result of COVID-19.

In addition, there is much to be learned from recent initiatives for guaranteed or universal basic income in the US. These pilot programs have shown many positive research-based findings including increased mental and physical health. Decrease in unemployment and increase in civil and familial participation. These outcomes show that GBI will increase women’s opportunities to accumulate wealth, improve family health, and reduce reliance on other governmental programs.

The fight for GBI is an important one in the state of Connecticut and CWEALF as an organization. Connecticut has one of the largest income inequalities in the country. Specifically, Hartford and New Haven have major issues in generational poverty (and compared to overall wealth in-state). More cash in people’s pockets keeps families financially secure and stimulates the local economy. Furthermore, GBI could reduce the racial income gap and finally bring many black families and individuals above the poverty line.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Madeline Granato, CWEALF Policy Director, for being my Community partner and guiding me throughout my project.

Thank you to Janée Woods Weber, CWEALF Executive Director for allowing me to partner with this amazing organization

Thank you to the whole staff at Connecticut Women’s Education and Advocacy Legal Fund for welcoming me in and allowing me to be a part of your amazing organization.

Thank you to Professor Stefanie Chambers for being my faculty sponsor and supporting me throughout my research.

Thank you to Professor Erica Crowley for her unwavering support and advice throughout my time at Trinity.

Thank you to Jack Dougherty and the Community Research Fellows program for creating this opportunity for me and other Trinity students.

Works Cited

Covert, Bryce. “New Study: Giving Mothers Cash Improves Children’s Brain Development.” Early Learning Nation, 22 Jan. 2022, earlylearningnation.com/2022/01/new-study-giving-mothers-cash-improves-children’s-brain-development/.

“Guaranteed Income.” Economic Security Project, 28 Feb. 2022, www.economicsecurityproject.org/guaranteedincome/.

Grant, David. “Hartford GBI Taskforce Interview” Interview by Abigail Nick. 25 February 2022

Hamilton, Leah. “HudsonUP Basic Income Pilot: Year One Report”. 9, Mar, et al. HudsonUP, www.hudsonup.org/.

Khan, Hannah. “Providence GBI Pilot Program Interview” Interview by Abigail Nick. 30 March 2022.

“Magnolia Mother’s Trust.” Springboard to Opportunities, springboardto.org/magnolia-mothers-trust/.

“Mayors for Guaranteed Income (MGI).” City of Providence, 9 Dec. 2021, www.providenceri.gov/mgi/.

Neighly, Madeline. “GBI Interview” Interview by Abigail Nick. 1 April 2022.

NewsHour, PBS. “A City Made the Case for Universal Basic Income. Dozens Are Following Suit.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 27 Dec. 2020, www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-city-made-the-case-for-universal-basic-income-dozens-are-following-suit.

Pinto, Andrew D., et al. “Exploring Different Methods to Evaluate the Impact of Basic Income Interventions: a Systematic Review – International Journal for Equity in Health.” BioMed Central, BioMed Central, 16 June 2021, equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-021-01479-2.

SEED, www.stocktondemonstration.org/#summary-of-key-findings.

SEED Data Dashboard, seed.sworps.tennessee.edu/findings.html.

Hugh Segal, et al. “The Need for a Federal Basic Income Feature within Any Coherent

Post-COVID-19 Economic Recovery Plan: FACETS: Vol 6.” FACETS, 25 Mar. 2021, www.facetsjournal.com/doi/full/10.1139/facets-2021-0015.