Imaginative interplay

Exhibition showcases dialogue between Graham Collection, works by current Haitian-born artist

Story by Andrew J. Concatelli

Photos by Nick Caito

“It’s really a feather in Trinity’s cap,” Leslie G. Desmangles says of the Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art.

The group of more than 320 paintings, sculptures, and objects is a treasure among the College’s art collection, according to the professor of religious studies and international studies, emeritus.

Desmangles’s friendship with Graham—who had a 40-year commitment to Haitian art—began in the 1970s and eventually led to Graham’s children donating her collection to Trinity in 2008, after her death.

“To have a collection that preserves the period of mid- to late-20th century Haitian art is of great value to the College,” says Desmangles. “It can be shown to students to illustrate things that we teach. And it allows the College to make connections with other scholars and can help put Trinity on the map.”

The College has presented several exhibitions drawn from the collection since its acquisition and continues to find new ways for the artwork to encourage discussion and to spark imagination.

Select pieces from the Graham Collection were part of a spring 2025 exhibition—Echoes and Collisions: The Art of Frantz Patrick Henry in Conversation with Selections from the Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art—in the Austin Arts Center’s Widener Gallery. The show was organized by Trinity’s Studio Arts Program and supported by the Center for Caribbean Studies.

An artist from Haiti who creates sculptural installations, Henry learned about the collection through Pablo Delano, Charles A. Dana Professor of Fine Arts. The two met when Delano was invited to speak at NXTHVN, a nonprofit arts incubator lab in New Haven, Connecticut, where Henry was completing a fellowship.

“What I saw in his studio was somebody who was trying to process his cultural heritage through the lens of contemporary art,” Delano says of Henry. “Artists don’t make art in a vacuum; they’re always informed by the context they live in and the art that came before them.” Trinity already was planning an exhibition of selections from the Graham Collection, and Henry was invited to respond to the historical pieces with works of his own. He chose eight objects from the collection with which he felt a personal, creative connection and wove in several of his sculptures.

The result was a site-specific exhibition in which pieces in different media, from different time periods, combine in unique ways to comment on themes such as the evolving meaning of religion and the concept of home. Henry mounted one painting from the Graham Collection (Jean-Baptiste Bottex’s Walls of Jericho, 1967) on the back of his steel sculpture that resembled a motorcycle frame (Resurrection Highway, 2024). The headlamp from that piece shone light through a sculpture from the collection (Serge Jolimeau’s Zodiac, 20th century), which then cast a shadow that framed another of Henry’s pieces (Vestiges of Light, 2024) mounted on the opposite wall.

“I like to interact with the space, to create the environment. I’m very interested in the ambience,” says Henry, who fashioned a new wall through the center of the gallery to represent a home’s front porch. “I wanted to communicate a traditional house you’d see in Haiti. The shotgun house is one where you have different rooms, but you have access visually to everything because it’s one straight line. I separated the gallery in two to create layering with multiple rooms. From one point of view, you get to see everything. It’s a complete work, and you’re inside of it.”

Henry says he enjoyed the challenge of having a dialogue with the collection and exploring where his own style and vision either clashed or connected with the historical pieces. In his exhibition statement, Henry says, “Here, cultural narratives intertwine, but sometimes misalign, reflecting the complexity of navigating art across different timelines. . . . The result is a dynamic tension, where past and present do not always seamlessly align but instead create new, unexpected meanings.

“This exhibition pays tribute to Edith A. Graham’s legacy while embracing the unpredictability of cultural dialogue,” he adds. “In this space, art becomes a force that collides, challenges, and ultimately expands our understanding of heritage and possibility.”

Echoes and Collisions came at a time when the mainstream art world was beginning to acknowledge the importance of Haitian art, Delano says. “In 2024, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., opened a show of Haitian art titled Spirit & Strength: Modern Art from Haiti,” he says. “And at the Venice Biennale last year, there was a whole room full of Haitian paintings, featuring some of the same artists represented in our collection.”

Haitian art generally is considered by scholars to be one of the most important examples of visual art of the African diaspora, Delano adds. “Haitian art speaks to the whole Caribbean experience, as Haiti was the first free Black republic,” he says. “This is meaningful for Trinity because the population of our home city of Hartford is over half people of Caribbean descent.” He says he hopes the Graham Collection serves as a resource to scholars and an inspiration to Caribbean people.

Delano says he believes that art collections and exhibitions at educational institutions like Trinity can stimulate ideas in ways that some museums do not have the freedom to do. “Colleges can produce exhibits specifically for the purpose of raising questions and issues for people to discuss; they’re not dependent on selling tickets or on catering to current trends,” he says. “The value that they create is an intellectual value that can be used by the greater community as well.”

Lisa Lynch, gallery director and organizing curator of the Widener Gallery, also says she feels that generating thought and debate is a crucial role of art on a college campus. “College collections enhance the community’s experience on many levels. These collections enable object-based learning for students and can be used for faculty research in various disciplines,” Lynch says. “Exhibitions that present these objects in dynamic and innovative ways can expand our perceptions and broaden our understanding.”

In recent decades, advancements have been made in expanding the traditional art history canon, Lynch says, and it’s important for Trinity’s collection to reflect this significant change. “This exhibit used the Graham Collection in a new way, and it celebrated Haiti’s rich culture. Amid the political strife and natural disasters that appear on the news, one can easily overlook the country’s vibrant artistic and cultural traditions,” she says. “I hope that this exhibition prompts students of art and art history to think about how they and their contemporaries honor or grapple with their heritage. Addressing the past or incorporating traditional objects into their work can lead to dissonance, harmony, or both.”

Art that looks at complex global histories and cultural relationships can be challenging, Lynch adds, but that’s often the point. “Sometimes art is beautiful and offers an escape, and sometimes it’s difficult and uncomfortable,” she says. “All of that promotes deeper thinking as we grapple with current local and global issues.”

Header image: Liminal Frameworks by Frantz Patrick Henry

About the artist

Frantz Patrick Henry is an artist of Haitian origin who has been living in Montreal since 2011. Henry, who graduated from Université du Québec à Montréal in 2019, received the McAbbie Foundation Sculpture Excellence Grant from the School of Visual and Media Arts (UQAM) for his installation Je suis nouveau ici (2020) and the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grant and the Explore and Create Grant from the Canada Council for the Arts for his upcoming solo exhibition in Toronto, Am I a hero? (September 2025). Having recently completed an M.F.A. in sculpture at Yale School of Art, he is a fellow at NXTHVN, an art incubator lab in New Haven, Connecticut.

A multidisciplinary artist, Henry explores the theme of “becoming” through sculpture, painting, and installation. He says that by appropriating everyday objects diverted from their function, his works often unfold in the form of a site promoting relations with the viewer, which invites them to an experience of self-reconstruction.

The College’s art collection

The Trinity College Art Collection includes more than 4,000 pieces, says Christina Bleyer, College librarian, associate vice president of libraries and digital learning, and director of special collections and archives at the Watkinson Library.

The collection was put under the stewardship of the Watkinson Library in 2023 and is overseen by the College’s first full-time art collection manager, Barbara Sternal, who originated the position at Trinity in spring 2024. About half of the total collection has been formally documented and cataloged—a process in the art world known as accession—and Sternal has so far added more than 750 pieces to the JSTOR digital repository.

“This is the first time the full art collection will be searchable and viewable by the public,” Bleyer says. “Anyone, even outside of Trinity, can search our art collection online, and museums can request to borrow pieces for exhibitions. We are committed to making the art collection accessible however we can.”

Bleyer says that the mission of the Trinity College Art Collection is to support teaching using original works of art, to preserve works of art entrusted to the Trustees of Trinity College, and to document and make such works accessible for study to students, faculty, and the public. Assembled largely from gifts by alumni and other donors, the College’s collection includes a diverse range of objects and numerous time periods. Individual collections include 14th– to 16th–century European paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation Study Collection, 18th– to 19th–century Japanese woodblock prints from the Philip Kappel Collection of Prints, Trinity College Presidential Portraits, the Edwin Blake Memorial Collection, the George Chaplin Collection, and the Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art.

“The Trinity collection has some really wonderful works in it, and the Graham Collection is the jewel in the crown,” Bleyer says.

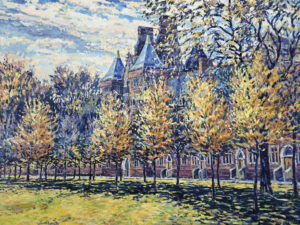

Various pieces from the art collection are on view in public buildings throughout campus and often are featured in special exhibitions in Trinity’s Widener Gallery. When not on display, some pieces are secured in an art vault on campus, while the rest are stored in the library.

“For faculty, staff, and students in all majors, pursuing a dialogue with works of art is the creation of new knowledge,” Bleyer says. “It’s a different way—beyond reading and writing—of engaging with what makes us human, offering a unique approach to the central questions that a liberal arts education asks and attempts to answer.”

Photo Courtesy of the Trinity College Archives

Echoes And Collisions

Echoes And Collisions

Frantz Patrick Henry Liminal Frameworks, 2025 Ephemeral Installation, wood, stylized pattern on wood, fiberglass, steel Dimensions variable Courtesy of the Artist

Jean-Baptiste Bottex (1918 – 1979) Walls of Jericho, 1967 Oil paint on Masonite, 20 x 24” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College and Frantz Patrick Henry Resurrection Highway, 2024 Steel, lights, willow weaving, vacuum pump, plywood, 72 x 36 x 48” Courtesy of the Artist

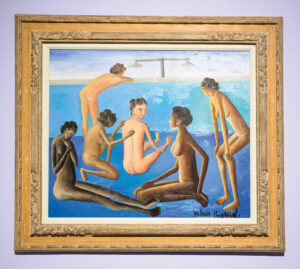

Wilson Bigaud (1931 – 2010) Untitled (Women in the Shower Room), ca. 1955 Oil paint on Masonite, 25 ½ x 21 ½” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

Amui Untitled (Noah’s Ark), 1980 Oil paint on canvas, 14 ½ x 19 ½” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

Sacha Tebó (1934 – 2004) Untitled (Woman and Dove), 20th Century Ink on paper, 20 x 24” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

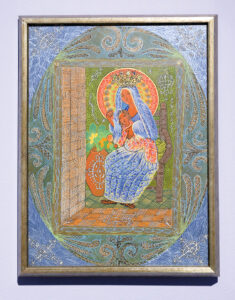

Saincilus Ismaël (1940 – 2000) Untitled (Madonna and Child), 20th Century Oil paint on wood, 15 x 11” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

Judith King Untitled (Red Hibiscus), 20th Century Ink and watercolor on paper, 4 x 3” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

Alix Roy (1930 – 2010) Untitled (Children Playing Dress-Up), 20th Century Oil paint on Masonite, 24 x 14” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

Serge Jolimeau (born 1952) Zodiac, 20th Century Metal, 40 x 34” Edith A. Graham Collection of Haitian Art, Trinity College

Frantz Patrick Henry Vestiges of Light, 2024 Sculpture: steel, cast iron, light 36 x 72 x 6” Courtesy of the Artist