Fresh air, fresh perspective

Students ‘immersed in science’ at Trinity College Field Station in Ashford, Connecticut

By Eliana Rosen ’27

Photos by Nick Caito and Helder Mira

As the vast, open sky stretches above them, two Trinity students watch birds fly by quietly while leaves crunch beneath their feet. They have just arrived at the Trinity College Field Station, about a 40-minute drive northeast of campus.

“It’s so peaceful out here,” says Alex Willard ’27.

Adds Hannah Flis ’27, “We always take a moment and appreciate the beauty around us, just standing in silence.”

As environmental science majors, the students come to the 60-acre field station to gain a deeper understanding of nature that can’t be replicated in the classroom or in a laboratory. Trinity students, faculty, and staff use the field station for research, teaching, and recreation through fieldwork, class outings, and club activities.

Willard says that exploring the field station property provides a unique perspective and a peaceful atmosphere. “Because Trinity is in the city, sometimes it can feel far away from nature,” he says. “At the field station, you immediately feel transported and farther away than you are.”

NATURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Located in Ashford, Connecticut—in a region of the state known as the Quiet Corner—the field station comprises two pieces of land owned by the College: the 48-acre Fiano parcel and the 10-acre Bourne parcel. The two parcels abut the Church Farm property, owned by Eastern Connecticut State University, and the Joshua’s Trust parcel.

Jonathan R. Gourley, principal lecturer and laboratory coordinator in the Environmental Science Program, has taught earth science and environmental science at Trinity for 18 years and says the field station is a valuable, hands-on resource. Students in his introductory classes conduct research by making observations and doing experiments in the Mount Hope River that flows next to the Bourne parcel and on the field station property.

“Students compare the rivers by studying the aquatic insects, as they are great indicators of water quality. If you have healthy bugs, you have a healthy food chain, healthy fish, and an overall clean river,” Gourley says. “Mount Hope is an idyllic Connecticut stream with fish and living organisms. Trout Brook [in Hartford] has fish as well, but it’s a far more stressed environment; there are no trout there anymore.”

In addition, the field station land is home to a pond with a large beaver dam and a wide variety of plants, trees, and animals. Gourley and his students mapped out these parcels and installed boundary markers and other signage.

SEVERAL SUBJECTS

The field station also offers opportunities for those pursuing academic areas outside of environmental science, including biology, neuroscience, and psychology. Susan A. Masino, Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of Applied Science, encourages her students to explore the field station to study the connections between brain health and nature and to encounter those connections firsthand.

“The experiential learning at the field station is something that cannot be done in the classroom, laboratory, or on the main campus. And it feels extra special because it is part of the College,” says Masino. “It is important for everyone to learn about our land and water. And having land to connect to is vitally important for our collective health. Students are excited to come back and visit over time and are happy just to know it is there.”

Gourley notes that student interest in the field station has led to the development of independent studies, including those by Flis and Willard. They are particularly interested in conducting tree-ring research, known as dendrochronology, to date abandoned chicken coop foundations on the property.

At the field station, says Flis, “the environment has grown up around them. We want to use tree-ring cores to date the structures and, using that information, determine when the structures were abandoned.”

Flis and Willard hope to pursue this research as their integrating experience—a requirement of the environmental science major—applying the lessons they’ve learned to their future endeavors.

“I came into college knowing I wanted to major in environmental science but not really knowing what I would want to do with it,” Flis says. “After exploring this space and working out in nature, I know I want to continue to do research.”

Willard hopes to pursue a career in conservation. “Growing up in a city, it was hard to find natural places for me to explore. These places got harder and harder to find, and the ones that I did have were more polluted and less of a free space. As I got older, the abundant populations of my favorite animals were significantly diminished,” says Willard.

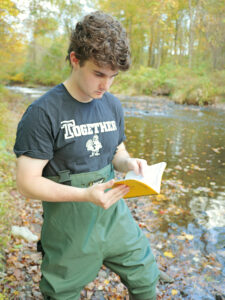

Students Harper Siemens ’26 and Scarlett Jago ’27 say that the research they conducted in the field station’s river gave them a better grasp of concepts learned in their “Introduction to Earth Science” classroom on campus.

“Stepping into the waders and going into the river, you just feel completely immersed in science,” says Jago. In one exercise for the course, students measure discharge—or flow—of the river using simple tools. Jago says, “We then compared our data with the real-time U.S. Geological Survey discharge of the Mount Hope River and used the historical flow data to make a graph on the recurrence intervals of a 100-year flood for this section of the river.”

IN THE OUTDOORS

The field station—which also is used as a destination for the Quest Leadership Program, Trinity’s outdoor orientation program for incoming students—can be a place to reflect and to ease stress. “After a tough week of class and volleyball, I remember going out to the field station during peak foliage season and just walking into the river. I was very sore, and the coolness of the river relieved my stress,” Jago says. “For a moment, I was just standing there, being outside and enjoying the fresh air, and I knew that I wanted to be an environmental science major.”

Siemens adds, “Sometimes students might dread going to class or have a lot on their mind, but here it makes learning more immersive and fun.”

Gourley says he believes that expanding access to and use of the field station could help all students see intellectual concepts in action and develop skills to support any academic or career path they choose.

“Beyond helping students conduct labs and teaching, I have been slowly trying to raise awareness of the property—to our deans, to our faculty, to our students—to encourage other possible projects,” Gourley says. “The field station is an important piece of the Trinity community that should be recognized and celebrated.”