I was drawn to create an interdisciplinary study between the visual analysis of fragmented sidewalks and the psychological impacts on pedestrian life in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay. Most times, many people do not think of sidewalks as research opportunities, but to me, they are essential spaces for everyday life. My goal was to understand not only how sidewalks look and function, but also how residents feel while using them.

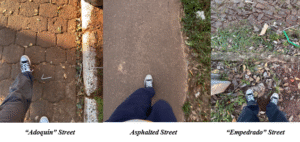

To begin with the process, I read articles on urban walkability and environmental psychology, as well as listening to podcasts and watching videos that explored how urban design shapes daily experiences. Then, I spent a month in Ciudad del Este walking its streets, observing, and collecting evidence. I documented sidewalks through photographs, video clips, and timelapses. To organize my analysis, I created a simple 3-point scale (poor, average, good) and applied it to a series of measuring factors across the city’s sidewalks. I selected three different urban contexts: First, asphalted streets in high-mobility areas, usually downtown and main avenues. Second, “adoquín” streets in areas (formally planned residential neighborhoods). And lastly, “empedrado” streets (uneven stone paving) in outer neighborhoods (often with little to no formal planning).

The selection of streets were randomised. However, I selected 2 streets per urban context. On each street, I analyzed both sides over at least two blocks, giving a more balanced picture of how fragmentation looks within the city. Alongside this visual work, I conducted four in-depth interviews with residents who regularly walk and who do not own cars. I recruited them through an online flyer, asking about their everyday use of sidewalks.

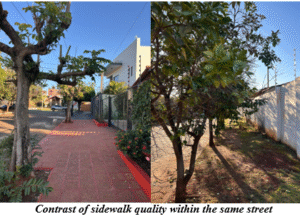

After these processes, I discovered something more complex than I expected. Residents consistently described planned residential areas as having the “best” sidewalks among other areas. Yet, my block-by-block analysis rated those same sidewalks only as “average” with extreme fragmentation even within the same street. A single block could sections that were smooth and functional as well as others that were broken, obstructed, and even poorly maintained. As another resident noted: “Some sidewalks are just horrible, you’ll stain your shoes because there’s water everywhere from the broken pipes, or trip on loose stones and fall. It’s a disaster.”

In contrast, asphalted streets (including downtown areas) with high-mobility and outer empedrado residential neighborhoods were rated as poor quality across most blocks. Another problem to be highlighted is that accessibility measures were almost absent everywhere, meaning there were zero ramps or other inclusive design elements present.

The interviews revealed that most residents use sidewalks mainly for commuting rather than for enjoyment of their surroundings. Residents mentioned avoiding walking at night as well as sidewalks being treated as extensions of private property, such as for business displays, decorations, or even car parking. Some residents even mentioned: “In Paraguay, we don’t feel like we are part of public spaces, and that’s also because these spaces are not really prepared to be public.” This contributed to the feeling that sidewalks were not truly public spaces for lingering or collective use.

Overall, this research project highlighted the value of combining psychology and urban studies, two fields whose intersection sometimes is overlooked. Bringing them together allowed me to see sidewalks not only as a physical infrastructure but also as spaces that constantly shape people’s emotions, behaviors and sense of belonging in the city. The findings suggest the need for stronger regulation and accessibility while also raising community awareness that sidewalks are shared public spaces, not private extensions. Although homeowners have the right to use sidewalks in front of their properties, they also share the duty to maintain and keep them accessible, and care for them as part of the city’s public treasure. So, small as they may seem, sidewalks tell powerful stories about how cities function. In Ciudad del Este, that story is highlighted through fragmentation but also as an opportunity to create more inclusive and engaging urban environments that truly invite people to walk.

Photos taken by Alex Goiris as part of his summer research.