When asking older Americans what they miss about college, I kept getting emotional answers: the people, the freedom, the sense of belonging, the feeling that life was somehow fuller. College is remembered as a golden age, a brief period when friendships came easily and everyday life felt alive.

When asking older Americans what they miss about college, I kept getting emotional answers: the people, the freedom, the sense of belonging, the feeling that life was somehow fuller. College is remembered as a golden age, a brief period when friendships came easily and everyday life felt alive.

But what if that nostalgia isn’t really about youth at all?

What if Americans love their college years so intensely because, for many of them, it’s the only time in their lives they live in a place designed at walking speed?

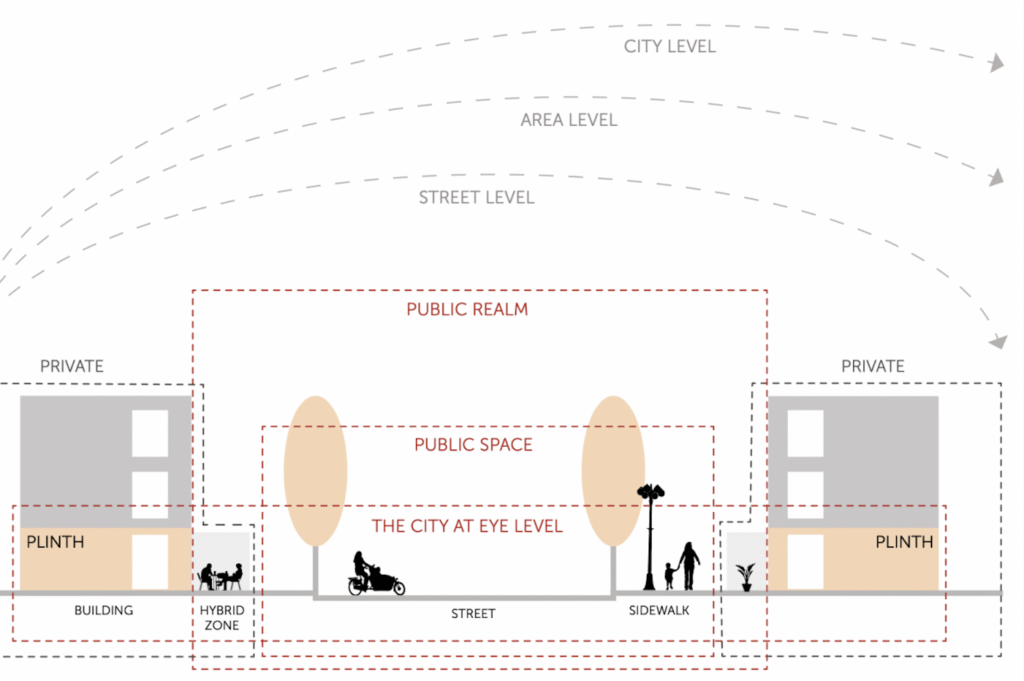

In Cities for People (available to loan from Raether Library!), Jan Gehl argues that cities are not experienced from above or through traffic models, but from the ground, at roughly five kilometers per hour. This is the speed at which we notice faces, overhear conversations, and decide to stop, sit, or change direction. It is the speed at which public life becomes possible.

Gehl distinguishes between necessary activities, like commuting or running errands, and optional and social activities, like lingering, people-watching, or striking up conversation. Optional and social activities only happen when the environment invites them. When distances are short, streets feel safe, and there are places to pause; life spills into public spaces.

College campuses in the US, often unintentionally, get this exactly right.

On a typical American campus, most daily needs are within a ten-minute walk. Housing, classrooms, libraries, cafés, green space, and social venues sit close together. Routes are designed for pedestrians. Cars are present but rarely dominant. There are benches, steps, lawns, and edges where people naturally linger.

As a result, social life doesn’t require planning. You run into the same people again and again. A short walk to class turns into a conversation. Sitting outside feels normal, not performative. Public space becomes a shared living room rather than something to pass through as quickly as possible.

None of this is accidental. It’s the product of proximity, repetition, and comfort – the exact ingredients Gehl identifies as necessary for public life.

And then, after graduation, it disappears.

For many Americans, adult life means moving into environments shaped by zoning codes and road hierarchies rather than human interaction. Housing is separated from work, from shops, from social life. Distances stretch. Sidewalks thin or vanish entirely. Social interaction shifts indoors or, even worse, online.

Friendships now require calendars, cars, and advance notice. Casual encounters become rare. Public spaces, if present, are often uncomfortable to stay in: too loud, too fast, too exposed, or simply absent. What feels like a personal loss is often a spatial one.

The problem isn’t adulthood. It’s the built environment.

College didn’t feel special because people were younger. It felt special because it allowed everyday life to happen without friction. What many people describe as nostalgia is often a response to leaving the only environment that made everyday social life easy.

Gehl’s work insists on the opposite. Cities do not need big gestures to become livable. They need sidewalks worth walking on, distances worth crossing, and public spaces that allow people to exist without buying anything or being in transit.

College campuses are not utopias. But they are proof: that when spaces are designed for people rather than cars, life shows up on its own; that the “best years of your life” feeling is not about time passing, but about space working.

The real tragedy is not that college ends. It’s that, for so many Americans, walkable life ends with it.