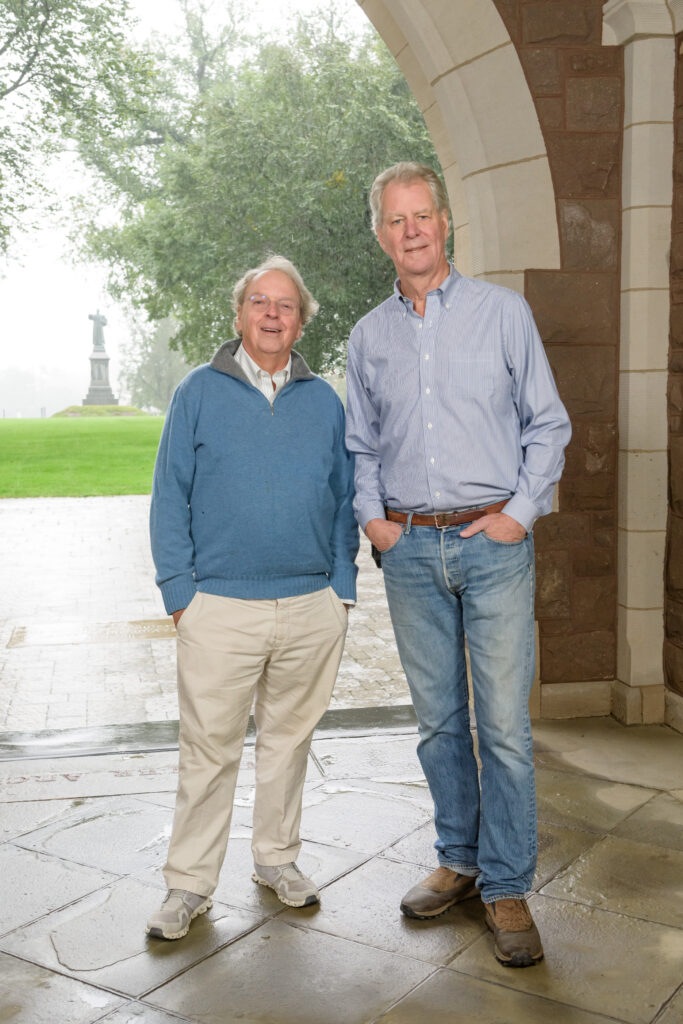

From roommates to writers

’72 classmates Peter Wheelwright, Bill Miller pen novels

Story by Mary Howard

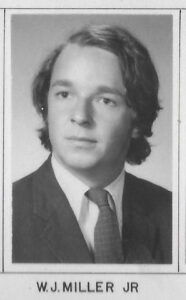

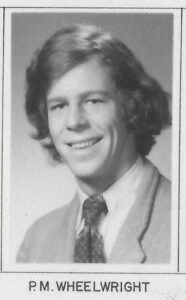

It wasn’t obvious during their time as Trinity College students that Peter Wheelwright ’72 and Bill Miller ’72 would become writers. Wheelwright chose to major in studio arts because he “didn’t want to write a paper ever again.” Miller, an English major, dropped out of his creative writing class with celebrated poet Hugh Ogden. “I regretted it later,” he admits.

But in 2022, the former Trinity roommates published well-received novels. Wheelwright’s The Door-Man (Fomite) was listed as “One of the Best Books of 2022” by The New Yorker. The book combines fact and fiction as it tells the story of three generations of families and their connection to a paleontological discovery. He also is the author of As It Is on Earth (Fomite, 2012).

But in 2022, the former Trinity roommates published well-received novels. Wheelwright’s The Door-Man (Fomite) was listed as “One of the Best Books of 2022” by The New Yorker. The book combines fact and fiction as it tells the story of three generations of families and their connection to a paleontological discovery. He also is the author of As It Is on Earth (Fomite, 2012).

Miller’s book, Steel City: A Story of Pittsburgh (Lyons Press, 2022), examines growth and brutality in the author’s hometown, when Pittsburgh was in its golden age as the country’s leader in steel, food processing, and electricity. A reviewer on BookTrib.com says, “Steel City enthralls readers of historical fiction from the first page with an immersive plot set in the industrial sprawl and black smoke of Pittsburgh in the 1890s.”

Miller’s book, Steel City: A Story of Pittsburgh (Lyons Press, 2022), examines growth and brutality in the author’s hometown, when Pittsburgh was in its golden age as the country’s leader in steel, food processing, and electricity. A reviewer on BookTrib.com says, “Steel City enthralls readers of historical fiction from the first page with an immersive plot set in the industrial sprawl and black smoke of Pittsburgh in the 1890s.”

The two met during their first year at Trinity, introduced by Will Whetzel ’72, who grew up with Miller in Pittsburgh and attended boarding school with Wheelwright at St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire. “We all came from very structured, traditional backgrounds,” says Whetzel. But against the backdrop of the 1970s, their college years were less so.

Wheelwright, who grew up in Lenox, Massachusetts, admits to being a bit of a “rascal.” Kicked out of St. Paul’s as a senior—“I busted every rule”—he spent a year studying in England before arriving at Trinity, where his older brother, George, was a student. Wheelwright had an appetite for mischief and distinguished himself on campus by driving an old Jaguar while wearing goggles and a white scarf. “I was restless and fun loving,” he says.

Miller also had his wild side, taking many crazy road trips to nearby women’s colleges. “But somehow, we protected each other from going too far out,” says Wheelwright.

Miller also had his wild side, taking many crazy road trips to nearby women’s colleges. “But somehow, we protected each other from going too far out,” says Wheelwright.

During their sophomore year, they lived in a former office in Seabury Hall, with Whetzel and Hugh Mohr ’72, who passed away last May. “There were two great big rooms for the four of us,” recalls Miller. Wheelwright created his own den out of soundproof panels in an alcove, and a friend painted a giant image of the Hulk on one of the walls. There was even a dog, Poco, whom Wheelwright brought home from the garage where he worked part time. “She died six weeks after my first child was born,” he notes.

Wanting to stay connected, all four roommates pledged to St. Anthony Hall. It was a difficult choice for all of them, but particularly hard for Wheelwright, whose brother wanted him to pledge to his fraternity, Psi Upsilon.

“I remember that we all were in tears at different times that week,” says Miller. “It seems silly, in retrospect, but it shows how close we were.”

During their junior year, Miller and Wheelwright lived together in Ogilby. “There were a lot of fun and games, but it wasn’t all fun and games,” says Miller, who recalls spending hours in the library, “grinding out papers.” He also enjoyed English professor Richard Benton’s “Five Popular Fictional Forms” class, where he delved into Zane Grey, Robert Heinlein, and Raymond Chandler. “They resonated with me more than Jane Austen,” he says.

Wheelwright admits, “We probably had too much fun.” Though his class rank was consistently in the bottom 10 percent, he “stopped playing around” when he discovered architecture in the fall of his senior year. Professors Terry La Noue and Dieter Froese from Trinity’s Fine Arts Department organized an independent semester in SoHo, where students could apprentice with artists or architects. Wheelwright spent the semester with celebrated architect Charles Gwathmey. “It was a fabulous opportunity,” he says.

Wheelwright admits, “We probably had too much fun.” Though his class rank was consistently in the bottom 10 percent, he “stopped playing around” when he discovered architecture in the fall of his senior year. Professors Terry La Noue and Dieter Froese from Trinity’s Fine Arts Department organized an independent semester in SoHo, where students could apprentice with artists or architects. Wheelwright spent the semester with celebrated architect Charles Gwathmey. “It was a fabulous opportunity,” he says.

After graduation, he spent a year studying architecture at Cornell University before earning a master’s in architecture from Princeton University in 1975. He began PMW Architects in New York City shortly thereafter, and his work has been published in Architecture, Metropolitan Home, and the Journal of Architectural Education, among other publications. His pieces Kaleidoscope Dollhouse and Poolhouse, which he co-created with Laurie Simmons, are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Wheelwright also taught architecture at Parsons School of Design, The New School, from 1983 to 2017, serving as chair of the Department of Architecture from 1997 to 2007. It was there that he started to think seriously about writing. Influenced, in part, by his uncle and namesake, Peter Matthiessen, a novelist and recipient of three National Book Awards, Wheelwright began taking creative writing classes at The New School and penned a few short stories. “I can’t think of many better trainings than architecture to help one write a story—how to structure it, move through it, create the space of it,” he says.

One of those stories became his first novel, As It Is on Earth, which centers around a young college professor, Taylor Thatcher, who wrestles with his religious legacy and complicated family history. The campus described in the book is a “thinly veiled” Trinity, and Thatcher’s office is in a building reminiscent of Seabury, says Wheelwright. The book received an honorable mention for the 2013 PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Fiction, “which was validating,” says the author, who is working on his third novel.

Miller was so delighted when Wheelwright published his first novel, he threw his friend a book party in Manhattan, where they were both living. It also got him thinking. “If Peter could do it, maybe I could, too,” he says.

Miller’s first job out of college was as a reporter for The Day newspaper in New London, and he owned a summer weekly newspaper in Rhode Island for two years. He also wrote a successful blog, Who’s Your Favorite Beatle?, where he shared his film and theater reviews. But much of his professional career was spent at Time Inc., where he worked in the consumer marketing division for more than 30 years. He retired as a director of the department in 2016.

For Miller, writing Steel City was a labor of love. A native of Pittsburgh, he has been fascinated by the city’s past since he was a child. “I lived on the same street as steel man Henry Frick’s daughter, Helen,” he says. “In Pittsburgh, the history is all around you.”

The book took Miller almost five years to complete. “It was a year of research, a year to write, and then three years to find an agent and get published.” He says he chose to tell the story through a historical novel because it offered him more freedom. “I could shape the story the way I wanted within the bounds of historical fact,” says Miller, who has begun working on a sequel.

Wheelwright says, “Billy and I both share in our books an interest in research and history, imagining the inner lives of these real characters in history.”

Though they don’t see each other often—Miller and wife Warren travel between their homes in Rhode Island and North Carolina, and Wheelwright and wife Eliza divide time between their loft in Manhattan and a home in Upstate New York—theirs is a relationship of fondness and respect, says Wheelwright.

“And whenever we do get together,” notes mutual friend Whetzel, “we’re right back to where we were the first time we met.”