‘Always Something New’: Explore Book Recommendations from Trinity College Faculty

Vy Duong ’26 asked some Trinity professors to recommend interesting books to students and other members of the College community.

Last summer, Trinity College Assistant Professor of Neuroscience Sally Bernardina Seraphin received a Fred Karush Endowed Library Readership from the Marine Biological Laboratory Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Library to support her research project, Progress in Developmental Neuroscience: From E.E. Just, to the Present, and Beyond.

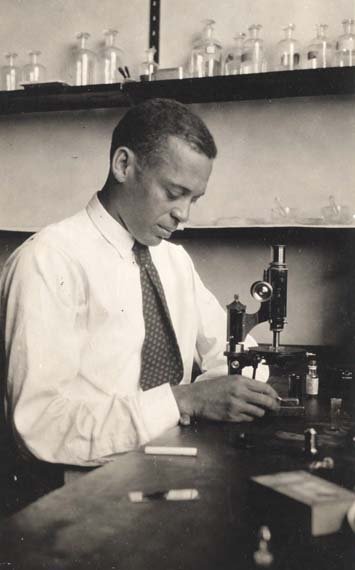

The readership allowed Seraphin to return to Woods Hole, Massachusetts, in June and July, where she had spent 10 weeks each of the previous three summers conducting research with Trinity students as an E.E. Just Fellow. In 2024, Seraphin narrated a video about the life of Ernest Everett Just (1883–1941), the first African American student to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago and to work at the Marine Biological Laboratory, and became interested in further researching and contextualizing his early contributions to neuroscience. “Apart from us both being Black scientists who had spent time at Howard University, I realized that we had a lot more in common,” Seraphin said.

Inspired by their shared interest in the ways in which early environmental experiences shape later development, Seraphin spent the month utilizing library archives to research Just’s contributions to evolutionary developmental biology. “I first read some publications by his biographer and other Black scientists who had been looking for seeds of future scientific innovation and understanding in his work. In the process, I actually had some interesting revelations about Just,” said Seraphin. “Not only did I confirm that he was an early evolutionary biologist, but he was ahead of his time in many ways.”

Seraphin explained that Just pioneered a comparative and holistic approach in developmental biology, in stark contrast to his contemporaries who favored a more mechanistic approach. “In one of Just’s early papers, he supported his argument with evidence from 29 groups or species,” Seraphin said. “Seeing that, 100 years ago, he was creating evolutionary arguments by comparison within as well as across species was really validating.”

“All the neuroscience courses I teach at Trinity mirror what Just was doing, connecting insights from cell and developmental biology with ideals about human society, collaboration, and cooperation,” Seraphin added.

Seraphin also sought to contextualize contemporaneous commentary regarding the ethics of Just’s funding sources. “He struggled to get funding for his research in the United States and went to Europe. He did research in France, Italy, and Germany before WWII, where he was able to get funding and worked in some very renowned research institutions,” she said. Ultimately, Just was captured when Germany invaded France in 1940, placed in a prisoner-of-war camp, and then sent back to United States, where he died shortly after being repatriated.

“I think the assumption that Just would share the beliefs of his benefactors is naïve. He was prevented from delivering his Valedictorian Address at Dartmouth because of his race,” Seraphin said. “There is no way that he would have been so enamored by European culture that he would disregard the rising hate and anti-Semitism.” Seraphin added that Just left an unpublished book, The Origin of Man’s Ethical Behavior, that she said would have firmly positioned him as against eugenics.

In the future, Seraphin intends to share the results of her research through public outreach resources like The Conversation and The Academic Minute podcast. She also has been in contact with other former E.E. Just Fellows and contemporaries at Dartmouth and Howard about holding a symposium on Just’s life and scientific contributions. “There is more interest in his work in the last 20 years than there was previously. He’s seen as increasingly relevant, and his brilliance is being noticed,” Seraphin said.

Ultimately, Seraphin’s month conducting research in the archives at Woods Hole proved to be fruitful. “Graduate school was really the last time I could just sit, read, and absorb. In science, you’re always reading with a purpose, with a next experiment in mind,” she said. “Reading Just’s work, experiencing his writing through my lens as a Black woman, a scientist, and as someone who is firmly influenced by evolutionary theory and social justice, it was a very nourishing experience.”