Q&A: Trinity Alumna Featured in HBO Documentary about Election Security

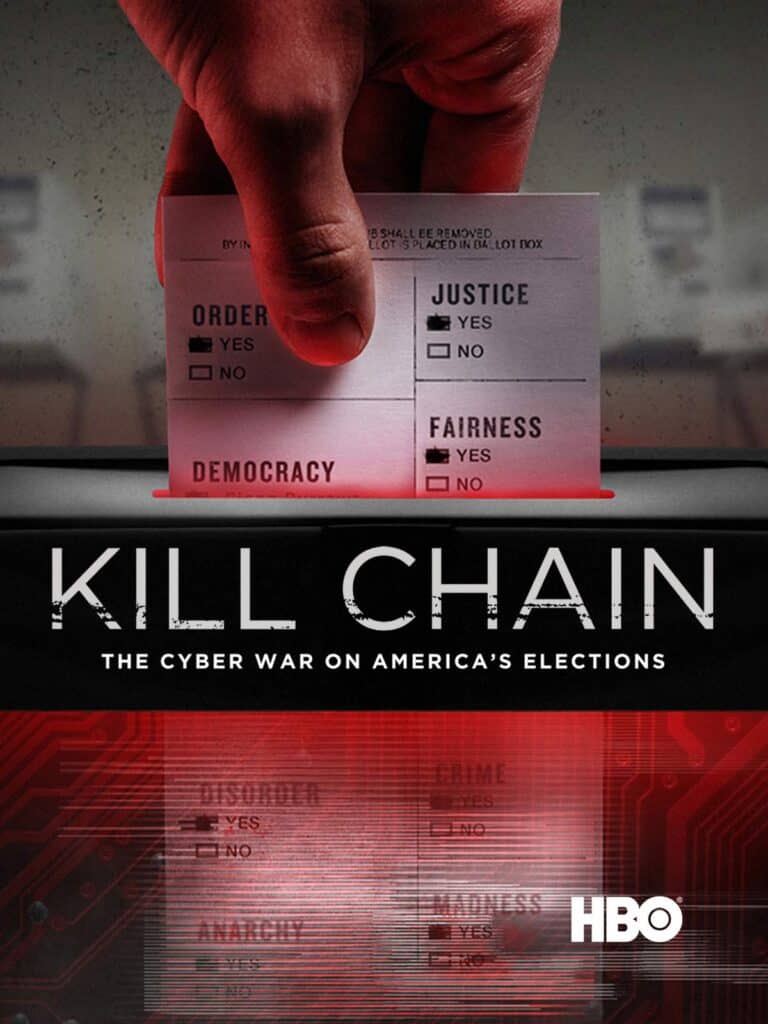

Maggie MacAlpine ’09 has worked in the election security and cybersecurity field since her time at Trinity College, where she completed both a major in English (focusing on creative writing) and a self-designed interdisciplinary major in ancient Mediterranean civilization, as well as a minor in Italian studies. MacAlpine grew up in New Hampshire, where she is based today. She’s the co-founder of Nordic Innovation Labs, a global technology solutions company that offers election security as one of its primary services. MacAlpine and Nordic Innovation Labs were featured in the HBO documentary film Kill Chain: The Cyber War on America’s Elections, which debuted in March 2020 and is available to stream on HBO Max.

What sparked your interest in the election security field?

I sort of not-jokingly say that the 2008 recession had a big hand in how I ended up in election security. After a great deal of searching, I ended up at a start-up specializing in election auditing and security, which was a surprise given my liberal arts focus at Trinity, but I grew to love the field. I’ve worked in and out of the world of election and cybersecurity ever since.

Why is election security an important concept for people to be aware of?

I would hope that the security of our elections is a matter of concern for all people! If we can’t trust federal elections, or an accurate reporting of the intent of people, then basically democratic society falls apart. Addressing the potential vulnerabilities in machines prevents widespread disruptions or falsification of an election. Election security is pretty critical for anyone living in a democratic country.

What is something misunderstood about the election security field?

I think lately there’s been a focus solely on the tabulation aspect—which is the voting machines themselves—and experts have been trying to clarify that voting machines are not the only potential vulnerabilities. There are back-end systems, results recording, and online voter registration that need securing. There are a lot of aspects to election security, any number of which could cause major disruptions right now.

How were you involved with Kill Chain and what do you hope viewers gain when they watch this documentary?

I co-founded my cybersecurity consultancy with [election security expert] Harri Hursti, who is sort of the main character of the documentary, and I was introduced to the director of the 2006 documentary Hacking Democracy, where he’s also a major character. And I somewhat jokingly suggested to the director, Sarah Teale, when we met that they shoot something new to see what’s changed since then, which is mostly nothing. Voting machine vendors really did nothing to correct the issues raised in the 2006 documentary. And you could kind of see the lightbulb turn on in her head. Then we were involved in filming for the next three, almost four years on and off, with very long days. I mean, there was a lot of filming—much more than appears in the film, obviously, but I understand the cuts they made to streamline the story.

I co-founded my cybersecurity consultancy with [election security expert] Harri Hursti, who is sort of the main character of the documentary, and I was introduced to the director of the 2006 documentary Hacking Democracy, where he’s also a major character. And I somewhat jokingly suggested to the director, Sarah Teale, when we met that they shoot something new to see what’s changed since then, which is mostly nothing. Voting machine vendors really did nothing to correct the issues raised in the 2006 documentary. And you could kind of see the lightbulb turn on in her head. Then we were involved in filming for the next three, almost four years on and off, with very long days. I mean, there was a lot of filming—much more than appears in the film, obviously, but I understand the cuts they made to streamline the story.

I think Kill Chain is a really critical documentary. I think it’s very eye-opening and incredibly well-made. Voting is a serious issue. What the election security experts are very careful to do these days is to stress that just because we’re alerting people to vulnerabilities in election security in general, we are not saying that you shouldn’t vote or that there’s no point in voting. Quite the opposite. I would say what we really should be aware of is that there’s an incredible effort, domestically and internationally, with millions of dollars being spent, to disenfranchise voters. And if you choose not to vote, you are saving those people money and time; you are disenfranchising yourself. And in fact, casting doubt on the election is as much a vector for attackers like that as changing the results, if not more so in many cases. So, don’t walk away from this documentary thinking, “Oh, this just confirms that I shouldn’t bother voting.” You should take the opposite approach that it actually makes it even more critical for you to vote.

How would you describe Trinity’s role in preparing you for this career?

I was a big Classical Studies Department person. I took a bunch of courses with [Associate Professor of Classical Studies] Martha Risser. The reason I made ancient Mediterranean civilizations my major was because I had already taken almost more than a major’s worth of classics courses. But because of my Italian minor, I didn’t have time to take Greek and Latin. So, Professor Risser was incredibly accommodating in letting me format my own major, but she also kept my feet to the fire. I had to write a thesis and do a six-hour long exam (most majors only require one of the two, at least at the time). She wouldn’t let me slack off in putting together this major just to get a good grade. And I would say that it’s that spirit of inquiry, and the assistance provided by the department and Prof. Risser, that gave me the independence and curiosity which eventually led me into the election security world and more broadly into the cybersecurity world as a serial entrepreneur. My education at Trinity encouraged me to pursue big civic questions like that of election security and made it something that I was personally interested in, rather than just a job.