Q&A: Professor Emeritus Paul Lauter on his New Book, ‘Our Sixties: An Activist’s History’

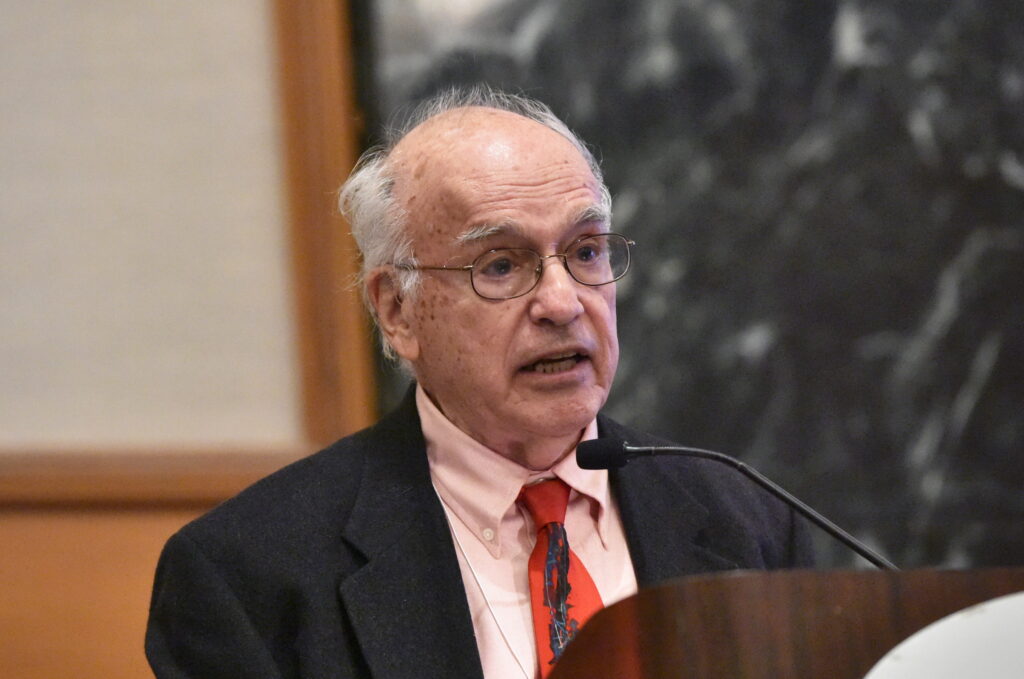

Paul Lauter, Allan K. and Gwendolyn Miles Smith Professor of Literature, Emeritus, at Trinity College, will give a free virtual talk called “1960’s Activism, Archives and the Now” on April 20, 2021, from to 5:00 to 6:15 p.m. For more information and the Zoom link to the program, click here or contact Kathleen Bauer at [email protected].

In his new memoir, Our Sixties: An Activist’s History, Paul Lauter, Allan K. and Gwendolyn Miles Smith Professor of Literature, Emeritus, at Trinity College, offers a look at the social justice struggles of the 1960s and a personal account of how his activism shaped his life and his work.

“My book comes out at an interesting time, when the whole legacy of the ’60s is being contested,” Lauter said. “There’s a meaningful discussion going on about where the country is headed, and that’s what the book is about, essentially.”

“My book comes out at an interesting time, when the whole legacy of the ’60s is being contested,” Lauter said. “There’s a meaningful discussion going on about where the country is headed, and that’s what the book is about, essentially.”

A former president of the national American Studies Association, Lauter is general editor of the groundbreaking Heath Anthology of American Literature, now in its seventh edition. In the 1960s, Lauter served as peace education secretary and director of peace studies for the American Friends Service Committee, and executive director of the U.S. Servicemen’s Fund. He worked in freedom schools in Mississippi, in Roosevelt University’s Upward Bound program, and was director of the first community school project in the nation. He also was one of the founders of The Feminist Press and its treasurer and an editor for 14 years.

Lauter taught at Trinity from 1988 until his retirement in 2015, serving for many years as director of American studies, English department chair, and the director of the graduate program in American studies. In 2018, Lauter received the Modern Language Association’s March Award, honoring his distinguished service to the profession of English at the postsecondary level.

In the Q&A below, Lauter discusses his history with the social justice movement, his time at Trinity, and the connections he sees between the events of the ’60s and today:

Where does your passion for social justice and activism come from?

I grew up in the Bronx and in Washington Heights. My parents were Roosevelt Democrats. I became part of Citizens for Kennedy at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in 1960 and helped to organize there. The more I was involved with that kind of politics, the more questions I had. Why were we getting involved in Vietnam? Why were we not supporting the civil rights movement? I didn’t know very much, but I knew it was right to oppose segregation. Very gradually and probably by accident, I got to know people who were activists, particularly in Students for a Democratic Society. A friend of mine from graduate school proposed that I should go to work for the American Friends Service Committee, a pacifist organization in Philadelphia, which is what I did. For the next 10 or 12 years I spent part of my time working with organizations like the AFSC and the U.S. Servicemen’s Fund, and part of my time teaching. I was involved in a whole variety of movement activities, some of which were in the civil rights movement or anti-war work. Around 1970 I became involved with the organization of The Feminist Press and with academic feminism. There was no single event or instance that made me a radical. It happened by slow stages; becoming involved, doing work that seemed good to do, and maintaining at the same time a foothold in academic work.

What impact did your social activism have on your teaching?

I began to ask myself the fundamental question: How does this movement translate into what you do day by day as a teacher? How does it change what you teach, and how you teach, and also who you teach? This later affected how I taught at Trinity and what I wrote about. Did it matter, for example, that the traditional canon of American writers didn’t include much in the way of African-American writers or women writers? If we wanted to see a more equitable society, what did we have to change in terms of what it was important for us to read and to think about? Who mattered? I began to teach courses with substantial representation of Black writers, women writers, Latino writers—writers who had never been part of a survey course in American literature. It was a process of reeducation for me and a different kind of education for my students. Along with my teaching, I began to develop a project called “Reconstructing American Literature.” That entailed, among other things, running a two-week conference at Yale in 1972. Coming out of that, people were saying that we needed a new anthology of American literature that doesn’t just have the traditional old white men in it, but has a greater variety of writers and of forms. We began the process of putting together this anthology, which is still among the most diverse.

What are some of your memories from your time at Trinity?

The spring before I came to Trinity, [Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of History] Cheryl Greenberg organized a conference of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. I came up to Hartford to be a part of that. That was an amazing moment for Trinity and for me personally. When I came to Trinity, I continued as director and general editor of the anthology and used it—even before it was published—in courses that I was teaching at Trinity. I discovered that students really took to it. They liked the diversity. They liked the challenge of having to rethink what was good literature. It was really a wonderful experience teaching this survey course in ways that were challenging to me and challenging to the students. It says something about Trinity that the people in the English Department were open to this kind of change in what we saw as important for our students to be studying. The English Department was a wonderful, supportive home for intellectual experimentation and diversity.

What was the process of writing this book like?

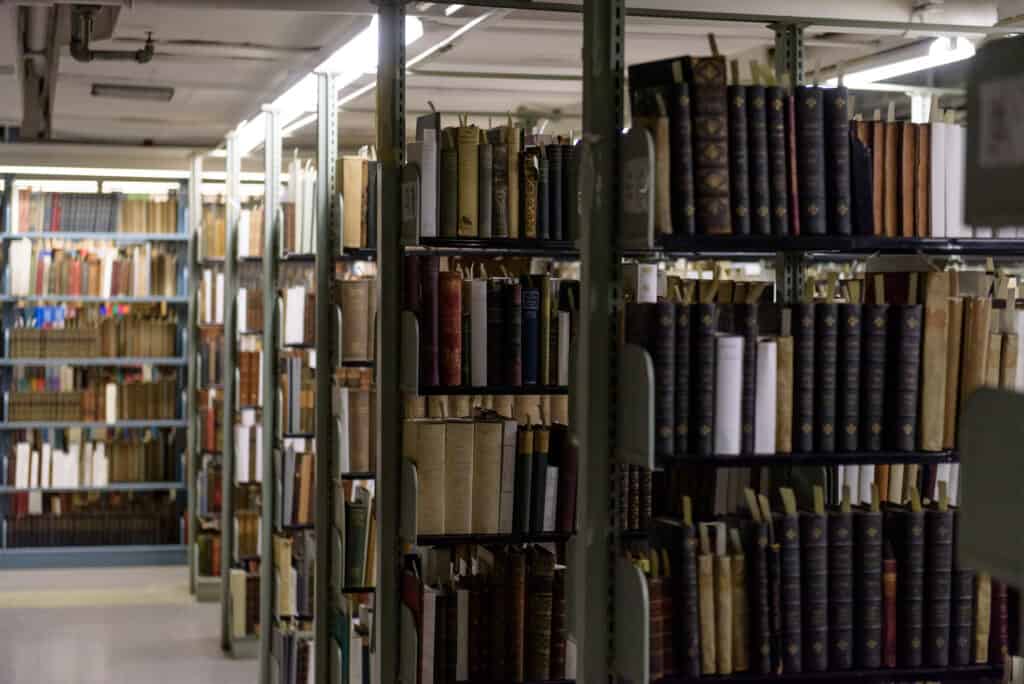

I’ve always written about literature and politics. Maybe 12 or 15 years ago, I began to try to write about not just literary study and cultural study, but to write out of the experience of being an activist in the ’60s and ’70s and on from there. I’ve compiled an archive—which is now in Trinity’s Watkinson Library—about the ’60s primarily, and about the organizations I had been involved in, including RESIST, which supports radical organizing. RESIST had accumulated a considerable archive, which we arranged for the curator of the Watkinson to take, along with personal materials from my own office at Trinity. There is now a really interesting movement archive in the Watkinson that some undergraduates and others have used. For this book project, at some point I had to decide I’ve read enough, I’ve gone through the archives enough, I have the material, and now I’ve got to write. That proved to be an interesting and slow process. I discovered it’s not so easy to write something that’s not just a memoir, but also social history, and to bring the two together.

What connections do you see between the events of the ’60s and those of today?

I recently wrote an article for the Bergen Record that made the argument that I first encountered Black Lives Matter in 1964. It seems to me that the insistence on change that Black Lives Matter embodies is very similar to the insistence on change that the civil rights movement of the ’50s and ’60s really pushed forward. That, in turn, has led to other demands and appeals for change. It has been the case in the United States that again and again, the issue of race—slavery, then Jim Crow, and so forth—has led the way, periodically, to rethink many things about our society. I myself have had to rethink what I had learned as a literary scholar and Ph.D. to expand the scope of what was important. That process is what, it seems to me, Black Lives Matter has put on the agenda in different ways, but in parallel ways.

There have been kinds of progress. It’s two steps forward and one step back. In 1964, very few Black people were allowed to register to vote in Mississippi. You could get killed, and people were, for supporting Black voter registration. That’s changed. Change is never one-dimensional and unidirectional. You do go forward, you achieve certain things. To use my own field, we will never go back to thinking about literary study as consisting of only white men. The fact that you read and study people like Toni Morrison, for example, means you’re not going to be narrowed in your understanding of what matters, who matters, and why. Change goes through cycles. You make some progress and you lose some. My general optimistic view of things is that we are in a somewhat better place, but it’s a constant struggle.

Editor’s Note: The Q&A was completed before Election Day. After the results of the election became apparent, Lauter added these thoughts:

Today I see a remarkable and spreading involvement in new progressive movements ranging from Black Lives Matter to #MeToo, Red for Ed to the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, and a Green New Deal to Medicare for All. You might not know much about this movement activity from the recent campaign, but these are issues that will not go away. Joe Biden insisted, correctly, that the election had to do with reclaiming the soul of America. Yes, indeed. That struggle, as I see it, has not now ended with the result of the election, but has only just begun.

Paul Lauter’s Our Sixties: An Activist’s History is published by University of Rochester Press (October 2020). For more information, visit www.boydellandbrewer.com or contact Casemate Academic at [email protected].