Conjuring up Witches and other Halloween Hooligans at the Watkinson Library

The prevalent commercial image of a witch riding a broom may have gotten an unlikely boost from an early author attempting to dispel the notion of witchcraft.

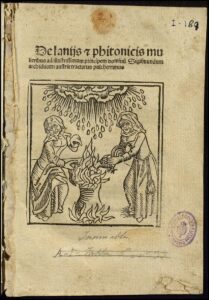

In his book from 1489, German legal scholar Ulrich Molitor made the case against the existence of witches. People who exhibited behavior categorized as witchcraft were simply delusional, he wrote.

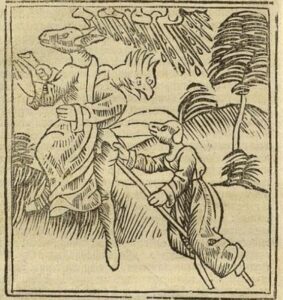

But Molitor included several illustrations in his De Lamiis et Pythonicis Mulieribus (Of Witches and Sorcerous Women). Although the title of his book is not a household name, the idea of a witch flying through the air astride a long wooden stick withstood the test of time.

“Unfortunately, there is more power in the illustration,” said Eric Johnson-DeBaufre, rare books and special collections librarian at Trinity College’s Watkinson Library.

Readers can see the illustration for themselves during the Watkinson Witching Hour on October 31, from 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. An edition of Molitor’s book dating to 1500 is on a table in the library’s reading room, located on the first floor of the Raether Library and Information Technology Center.

Archivists are inviting students to celebrate the holiday by glimpsing the evolution of ideas about witches and other Halloween hooligans within the collection materials.

“Witchcraft is a thing that had to be invented,” said Johnson-DeBaufre. “The assumption that everyone believed—or only commoners believed—in witches is untrue. It is exactly the opposite: the educated worked hard to convince people of the reality of witchcraft.”

The advent of the printing press helped belief in witchcraft proliferate, he said. The popularity of each point-of-view could be measured by the number of books that rolled off the printing press.

Of Witches and Diviner Women was written to counter Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum, usually translated as the Hammer of Witches. Malleus Maleficarium went through 12 editions in its first 35 years, said Johnson-DeBaufre.

“In a short time, it exerts a terrible influence on mainly women in Europe,” said Johnson-DeBaufre. Its claim that—incorrectly—identified the etymology of the word “feminine” as being formed by concepts that meant “minus” and “faith” also fomented the idea that witches were women. In essence, women had far less faith than men in God and so were more inclined than men to be witches.

“Debates played out within books the way you might see on social media,” said Johnson-DeBaufre.

“Debates played out within books the way you might see on social media,” said Johnson-DeBaufre.

In the early 1600s, when ideas of witches crossed from Europe to the United States, witchcraft found a broader audience.

Early colonies such as Connecticut wrote witchcraft into law as a capital crime—coincidentally listed before murder—that was punishable by death. These laws can be seen in material that is also on display at the Watkinson.

Between 1647 and 1724, 42 people were accused of witchcraft in Connecticut and 11 put to death, said Johnson-DeBaufre. That historic “wrong” led to political action as recently as this year. The State Senate approved a resolution in May absolving the dozens of women and men who were accused, convicted, and punished for witchcraft in the 1600s.

The accessibility of the early material goes beyond the tomes about witchcraft.

Another table in the Watkinson Library Reading Room is laden with readily identifiable publications: Trinity yearbooks. From those familiar pages, another popular symbol of Halloween—the skeleton—leaps forth.

Eric Stoykovich, college archivist and manuscript librarian, gathered the examples of skeletons in Trinity publications.

After the Civil War, he said, there was a lot of interest in the skeleton—it apparently was the subject of great student fascination. The fascination translated beyond the yearbook pages to student hijinks on campus, via incidents reported in early student newspaper, The Tablet, he said.

All of the books and papers can be handled by visitors without gloves; clean hands are all that is asked by Stoykovich and Johnson-DeBaufre. The materials are intended to be read and researched, they said.

“Otherwise, it’s just stuff on a shelf,” said Johnson-DeBaufre.