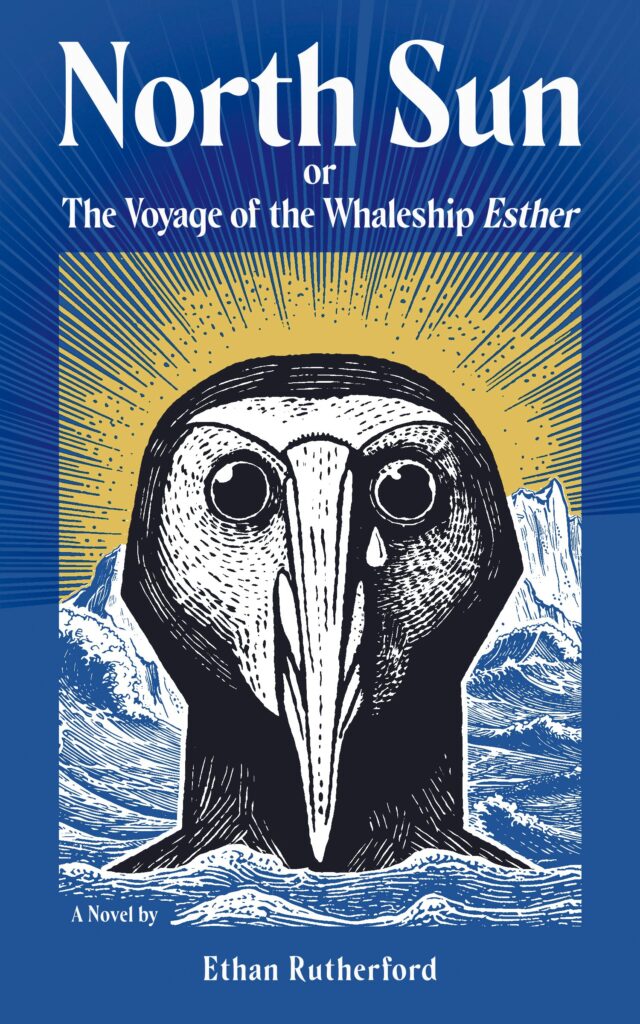

Associate Professor of English Ethan Rutherford, who earned a B.A. from Williams College and an M.F.A. from the University of Minnesota, recently embarked on a journey to write his first full-length novel, North Sun: Or, The Voyage of the Whaleship Esther, following his award-winning short stories. Here he talks about his inspiration and creative process as well as how teaching creative writing and fiction courses at Trinity College informs his work as a writer.

What kind of research did you do for the historical and nautical details of the novel?

North Sun is set at the end of the 19th century, during the final days of the American whaling industry—when the seas had been hunted nearly empty and whales were approaching extinction. The story begins as a traditional sea voyage, a classic whaling expedition. The crew sets out into the Atlantic in search of whales, but with little success. They round the Cape and continue all the way up to the Chukchi Sea in Alaska, which at that time was still an active whaling ground.

About half the book follows this traditional narrative of a whaling voyage. But then, midway through, things start to shift. A mysterious and vengeful spirit of the sea boards the ship—this character is called Old Sorrel. He has the head of a bird, the body of a boy, and is only visible to the cabin boys. His intentions are unclear, but from the moment he arrives, the voyage becomes increasingly strange and feverish, eventually spiraling into something much darker—at least from the crew’s perspective.

The research for the book came from reading everything I could find on whaling. I spent time at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, worked in their research library, and ordered all kinds of books. One especially important resource was In The Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whale Ship Essex, [based on] the real-life event that inspired Moby-Dick. It’s the story of a whale that destroyed a ship. I was particularly interested in polar whaling techniques, so I ended up with stacks of books—my wife teases me about them—with titles like Whales, Ice, and Men; Whaling in the Ice; The End of the Ice; and so on. I just read and read, and over time the story began to take shape.

I knew I wanted the ship to reach the ice, and I knew I wanted the book to engage with the brutality of the whaling industry—how it was an industry built on the ruthless extraction of natural resources to the point of extinction. For me, that was the chime for the current-day concerns that we have about the environment.

The structure of the novel is lyrical and haunting. How did you approach shaping the tone and pacing of the story, the ‘narrative arc’?

One of the great things about writing a sea voyage is that it comes with a built-in structure: You have the departure, the journey, and the return. So, there’s a natural beginning, middle, and end. What you then must figure out is what you put inside that structure to make the journey interesting and meaningful. How do you build it in a way that feels dynamic and emotionally resonant?

I knew from early on that I wanted the book to shift halfway through, from something relatively realistic, a voyage we’ve seen before, to something more surreal and fever-dream-like. That shift marked a deeper engagement with the ideas of extraction, brutality, and the cost—not just on the environment, but on the people involved in that violence. So, I had this internal midpoint I was writing toward.

But if you love the sea—and I do—and you love boats and knots and charts and all of that, it’s very easy to fall into the trap of writing a 700-page book that only appeals to the four other people who also care deeply about knot theory. I realized quickly that I needed to move the book quickly through time and space.

The way that came most naturally was to write in short chapters, which I started to think of almost as prose poems. In fact, I began thinking of the book as a kind of song cycle: each page its own song, capturing a moment in the voyage. Most of the chapters are a page or less. But each one has its own small arc—a beginning, a complication, and a kind of arrival.

That structure also helped with pacing. In the early parts of the voyage, when not much is happening—when it’s just “we woke up, more waves . . . still more waves”—that repetition can get tedious quickly. But this structure allowed me to jump ahead, to say, “A month later . . .” and keep things moving without losing the rhythm of the journey.

Another influence on that structure came from the ship’s logs I was reading. Alongside narrative accounts of whaling expeditions, I read a lot of primary sources—diaries and logs kept by sailors. What fascinated me about those was the tone: There’s no inflection, no prioritizing. It’s just raw data. “Sighted four whales. Caught one. Rendered four barrels of oil. Low on hardtack. Sam died.” Everything’s on the same level of importance.

There was something oddly powerful about that flatness, that repetition. It started to shape how I thought about storytelling. These logs would often compress the mundane and the surreal into the same breath. You’d get, “We were sailing as usual and then a flock of unknown birds appeared—never seen before.” And that’s it. No elaboration. The next entry: “Still having problems with the lines.” That kind of strange, haunting understatement really stayed with me as I was writing.

How did writing this novel compare with crafting short stories?

When I’m writing short stories, I usually can’t even begin until I know what the final paragraph is going to be, or at least where the story is headed. Once I have that final image in mind, I can reverse engineer the rest—figure out the best place to begin, how to shape the tension so it builds naturally toward that ending.

But I learned the hard way that you can’t do that with a novel. Writing a novel feels much more like a leap of faith. You just have to start walking—one foot in front of the other—without knowing exactly where it’s going, but with a sense of general direction.

Then, what you essentially end up doing is letting language lead the way. So, you put the characters together, let them start talking to each other, and see what happens. Then you pay close attention to what’s happening on the language level—what I’m interested in stylistically or rhythmically—and that usually gives you just enough momentum to come back to it the next day. That’s really how I move forward: one small discovery at a time. I’ll read what I wrote the day before, try to feel where it’s pulling me, and just follow that thread.

It also helped immensely to have the characters stuck on a boat, heading toward a fixed destination. No matter what else happens, the journey has to continue. That gave the novel a built-in sense of motion and constraint. I knew the setting would mostly be limited to this whaling voyage, and that containment made it easier to keep moving, even when I didn’t know exactly where the story would land.

How does teaching inform your work as a writer?

Oh, that’s a wonderful question! It absolutely informs my work—both in a general sense and in a way that’s very specific to North Sun.

More broadly, when you’re trying to help other people fall in love with literature—when you’re teaching stories you believe are worth studying, worth emulating, or at least worth carrying around in your head as you work through your own writing—you have to really understand how those stories work. Teaching forces you to slow down and pay close attention. If you’re going to teach a story, you have to know it well enough to explain how it functions on the page, which has made me a much better and more deliberate reader.

Teaching has also shaped how I approach drafts—my students’ and my own. One of the most helpful questions you can ask a piece of writing in progress is: “What are you trying to be?” And if you’re in the habit of asking that about student work—“What if this happened instead? What are the stakes here?”—you start to ask those same questions of your own writing. That kind of ongoing interrogation has really enriched my revision process. I’ll look at a draft of mine and think, “OK, what if this weren’t mine? Where is it working? Where is it falling short?” That mindset has been incredibly valuable.

More specifically, with North Sun, the teaching connection runs even deeper. One year, I was working with a group of thesis writers, and we were all struggling to stay on a writing schedule. So I said, “OK, no excuses—we’re going to write every day. We’ll hold each other accountable using a shared Excel spreadsheet. Each day, just log your word count and sign your name.” I thought, “Great, this will get them going.”

But then it felt totally fraudulent not to do it myself. So I joined them. I had a project I wanted to work on, and I started writing alongside them—day by day, word by word. That’s actually how North Sun began. So I owe a huge debt to those thesis writers. It felt disingenuous to ask them to commit to the daily work of writing if I wasn’t doing it, too. So they really held me accountable. That spreadsheet held me accountable.

What’s next?

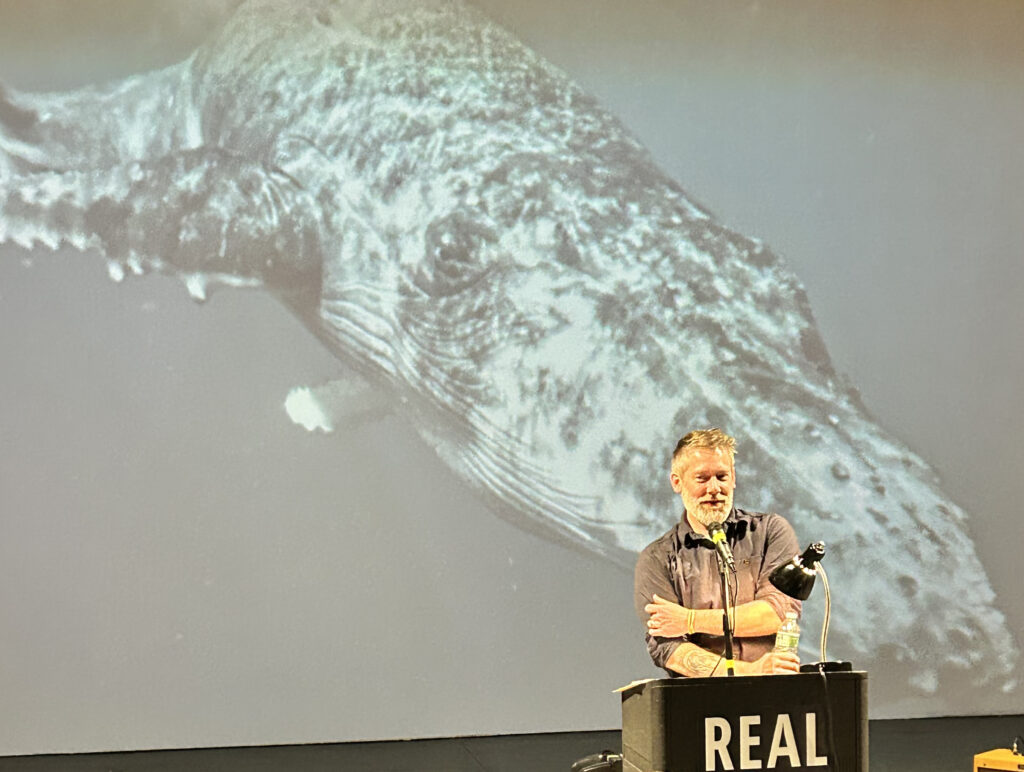

It’s a really fun stage. It’s that strange but exciting moment when the book is no longer yours; once it’s out in the world, it belongs to the readers. And that’s been a wonderful experience. I’ve been doing readings, talking to people about the book, and those conversations have been fantastic.

But now I find myself right back where I started with North Sun—back to the spreadsheet, back to putting value on showing up every day for a new project. This next book will be a contemporary novel—something completely different. I’ve been told I need to take a break from whaling, which is absolutely fair.

Right now, I’m in that early, generative phase where I have no idea where the story is going. I just know what I’m obsessed with. So every day, I sit down and write toward those obsessions and see where the act of writing leads me. That’s something I’ve really come to understand—especially through working with students—when it comes to long projects: You can’t think your way into the book. The writing itself is what tells you what the book wants to be. It’s only by making it—by doing the work—that all the little decisions start to reveal themselves.

And honestly, it’s the best place to be. The inner critic is quiet for a while, and you can just say, “Let’s have fun today—let’s see where this goes.” So that’s where I am now: back in that open, playful space, and it feels very alive.

Anything else you would like to share with the Trinity community?

The English Department has a wonderful run of professors publishing books: Sarah Bilston, Ciaran Berry, Francisco Goldman, and David Sterling Brown. It’s been fun to work with colleagues and see these long-term projects coming to be and getting out in the world.