A chance conversation with a colleague more than 20 years ago led to one of the most fulfilling research and writing projects Professor of Music Eric A. Galm has had as an academic. The year was 2004, and Galm had just arrived at Trinity as an assistant professor of music, specializing in ethnomusicology. He recalled the conversation with former Austin Arts Center administrative assistant Beatrice “Bea” Birdman about his travels to Tucson, Arizona, where he was excited to be attending a professional conference.

“Bea told me her mom lived in Tuscon. ‘She’s a Brazilian pianist,’ she told me,” said Galm. “Bea thought it would be nice if I met up with her while I was out there.”

Galm agreed to have dinner with Evanira Mendes. Mendes was delighted to entertain a visitor and took Galm to a local arts co-op store. It was there, when Galm heard Mendes whisper something under her breath while looking at an artifact, that Galm discovered that she had been a folklore researcher.

Galm learned that Mendes had worked with the São Paulo Folklore Commission during a critical time in its history. “I couldn’t believe when she began naming people with whom she had worked,” he said. “They were scholars whose work appeared in the first third of my doctoral thesis!”

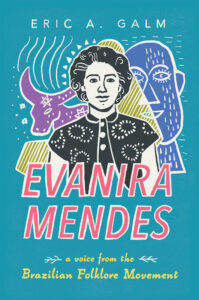

That initial conversation led Galm down the path of what would become a 20-year research journey resulting in the publication of his new book, Evanira Mendes: A Voice from the Brazilian Folklore Movement (University Press of Mississippi, 2025).

Galm learned that Mendes had become involved with the folklore movement by chance. Attending the São Paulo Music and Drama Conservatory in 1948 as a piano student, she was invited to work in the folklore archives, a move that ultimately took Mendes across Brazil to document the people and customs that made up the folklore movement.

In conversation with Galm, Mendes provided rich descriptions of her research trips. “She would talk about gathering with colleagues in rural areas where locals would share stories, songs, and dances,” he said.

These experiences brought up childhood memories for Mendes, who had spent so much time on her uncle’s farm.

“The memories came washing over her,” recalled Galm.

Mendes remembered story-telling strangers who would pass through town, offering to share their tales and songs in exchange for food and shelter.

Galm explained, “That was the living folklore that she didn’t even realize she was experiencing until she got to the conservatory and learned more about the history of folklore. Learning about the customs and traditions validated the people she had perceived as important growing up.”

One of Galm’s challenges as a researcher was finding supplemental information and sources to enhance Mendes’s descriptions of her research trips. He described the process as looking for needles in haystacks. When he was able to locate the original archives in which Mendes had worked, he discovered boxes and boxes of uncatalogued material that had fallen into disrepair.

Fortunately, Galm found his way to some digitized accounts that described in exact detail the expeditions that Mendes had told him about. “It’s good that I persevered to discover that level of detail,” he said. Galm collaborated with Douglas Johnson, Trinity professor of music, emeritus, to translate the reports and Mendes’s writings.

While Mendes was an important researcher, Galm found that her work was done mostly anonymously. “The directors would publish papers on folklore with materials prepared by anonymous commission workers and then take credit for the work,” he said.

While Mendes was an important researcher, Galm found that her work was done mostly anonymously. “The directors would publish papers on folklore with materials prepared by anonymous commission workers and then take credit for the work,” he said.

But Mendes took initiative as a writer. In fact, by the mid-1950s, she had started publishing weekly newspaper articles under her own byline. She wrote 75 articles—on everything from classical music and opera to music history and music theory—that ran in the Sunday arts supplement.

“Her column appeared alongside stories that might appeal to general audiences, such as popular names for babies and healthy food choices,” said Galm. “In many ways, she produced an early version of an online music course.”

Though Mendes was known locally for her column and even received a national medal of service to folklore—recognized along with major period authors and composers—she passed into obscurity over the years. Galm found that there were others for whom the same was true, peers of Mendes and countless others.

“Evanira lamented to me that a fellow researcher had not received recognition for the work that she had done,” said Galm. “When I began to dig into the work of many important scholars of Brazilian music, I found that Evanira’s colleague was named in the footnotes of their work. She had been an original research source.”

Galm, who has used sections of his book in his classes, says that one of the most gratifying parts of telling Mendes’s story was watching as Birdman listened to his students sharing what they learned about her mother. “Bea was passing through town, and I invited her into my class,” said Galm.

Galm is happy he was able to share a completed manuscript of his book with Mendes before she passed in 2022. He noted, “She was so moved that someone had validated the work that she’d done so many years ago.”

Cover photo by Isabella Galm