Always Play to the Whistle

Matt Glasz ’04

In the fall of 2003, I was a co-captain on the Bantam football team, and we were on the brink of achieving Trinity’s first undefeated season in a decade. As we headed into the final road contest of the year, we not only had an unblemished 6–0 record but also had outscored our opponents 175 to 16 (a nearly 27-point average margin of victory).

Despite our dominance, a series of uncharacteristic miscues including a fumble, a missed field goal, and a blocked extra point had put us in unfamiliar territory, and we trailed Amherst 14–6 late in the third quarter. For the first time all season, we found ourselves behind in a game, and I was racked with frustration over potentially seeing our perfect season slip away.

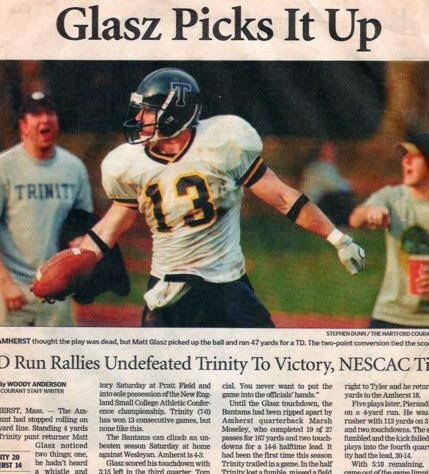

With just over three minutes left in the third quarter, we forced Amherst to punt from their own 27-yard line. Their punter shanked a kick off the side of his foot, angling the ball toward our sideline. After a high bounce, three Amherst players converged on the football as it rolled to a spot at the 47-yard line, nestled just outside the numbers. I was not the designated return man on the play and had been blocking a player further downfield along the same sideline. However, my eyes never left the ball on my way toward the bench, and as the three Amherst players began walking away, I noticed two things. First, none of them had touched the ball, and second, the ball was still moving, ever so slightly.

In an instant, my feelings of frustration and anxiety were replaced with the exhilarating possibility of risk and opportunity. The official, who had positioned himself, along with the ball, at the 47-yard line, took a step forward to blow the whistle and end the play. But before he could, my instincts lunged me toward the ball. I scooped it up and took off down the sideline sprinting as fast as I could before anyone knew what had happened. Two of the three Amherst players froze, then looked over their shoulders only to see me halfway to the endzone. Chaos ensued as players, coaches, and fans began to realize what had happened. I circled the end zone with my hands outstretched in disbelief at the sudden turn of events. The officials convened and correctly ruled (in my humble opinion) that the touchdown would stand.

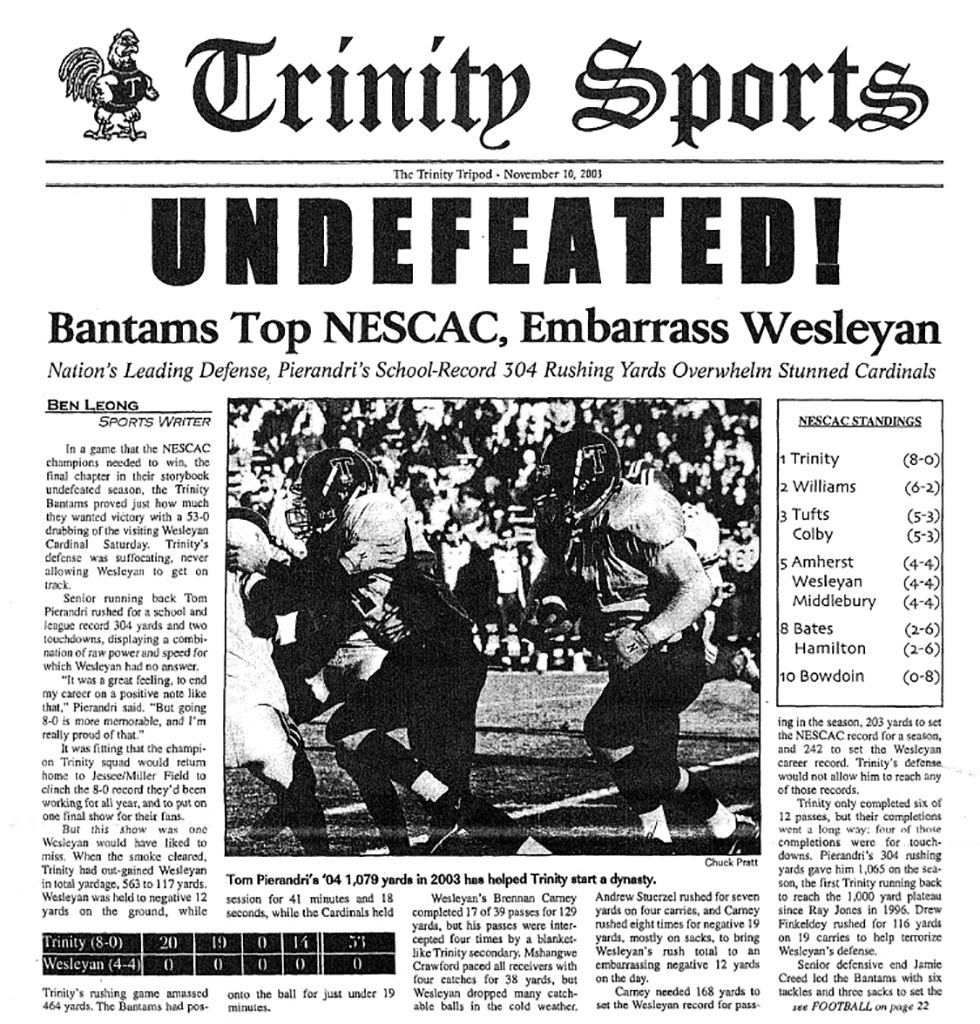

The momentum had swung like a tidal wave. While those six points merely closed the scoring gap, the nature of the touchdown and the emotional lift it provided shifted the outcome of the contest. A successful two-point conversion run by Tom Pierandri ’04 tied the game at 14 apiece. Two plays later, Duane Tyler ’05 intercepted an Amherst pass and returned it to their 18-yard line. Just five plays after that, Pierandri scored a touchdown to finally give us the lead and ultimately a victory that clinched an outright NESCAC championship. One week later, we decimated Wesleyan 53–0 on Jessee/Miller Field to cap an undefeated season.

This was our 13th straight victory, and the Trinity winning streak would eventually reach a NESCAC record 31 consecutive games. Of all the wins over that span, this was arguably the most dramatic, and of all of my Trinity memories, it is certainly the most vivid, likely because I’ve retold it countless times in the nearly 20 years since it happened. I always enjoy telling the story and consider it my small Trinity claim to fame. Every year when Trinity plays Amherst, it serves as a reminder that in football, as in life, always play to the whistle.