A Greyhound Kind of Mood

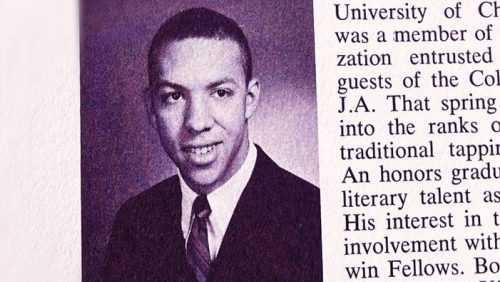

A Bicentennial Essay by Robert Stepto ’66, who retired in 2019 as the John M. Schiff professor emeritus of African American studies, English, and American studies at Yale University, where he taught for 45 years.

Prologue

I’m honored that a selection from “A Greyhound Kind of Mood” is appearing in a Trinity Bicentennial publication. It is an essay I was compelled to write in the 1990s, when so much was going on for me. My sons were no longer children, my parents had just passed away, and I was becoming absorbed with researching family history and writing personal essays. Trinity was much in my thoughts, what with my 30th Reunion in 1996 and with me stepping down from the Trinity Board of Trustees in 1992 after 10 years as a trustee. Where did I start with Trinity memories? I started with freshman year and the “Greyhound Mood” I found myself in. Reading my essay will convey what Trinity and most other men’s colleges were like 60 years ago. It is a true improvement and blessing that Trinity has men and women students and faculty and is far more communal and international in its studies, interests, and commitments. Reencountering my freshman year lets me see all the more how I grew to create a future for myself. I also see a world Trinity had to transform in order to become its present resourceful self.

— Robert Stepto ’66, February 2024

Excerpt from “A Greyhound Kind of Mood”

Note: Originally published in the winter 2001 issue of New England Review, the full essay may be found on the Review’s website and on JSTOR. It was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and was named a Notable American Essay of 2001. The first part of the essay recounts a student experience at a time when the cruelty of racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia were woven more deeply into societal norms. This excerpt is the last part of the essay and takes place in summer 1963, when Robert, a rising sophomore, is home working full time and is required to go to summer school after failing an engineering class at Trinity.

In the midst of this engulfing stupor, my mother one day reminded me not only that dinner was ready but that I was to start summer school that evening. Summer school! Of course, I hadn’t really forgotten it, for how could I forget why I had to go? I had flunked engineering drawing and had to make up the credit. But here it was, and so soon. I wanted to go back to sleep, but I ate something and borrowed my mother’s car to dash to class.

Only as I drove north on Stony Island and then into the gentle curves of Jackson Park did I begin to assemble a reasonable recollection of what course I had signed up for and why. It was a philosophy course to be taught by a University of Chicago professor I’d vaguely heard of named Walker Sawyer. The topic was pre-Socratic philosophy, which was already a puzzle since it was news to me that philosophy had existed before Socrates. But I figured everything would be okay since “Walker Sawyer” sounded impressively intellectual and I had noticed his books in the bookstore. And besides, the class was going to be in the same downtown building where I’d gone to prep for the SATs. This was going to work.

When you are young you think you can learn anything. It is just a matter of cracking open the book and reading long and hard. When that works, you believe you have “applied yourself.” When it doesn’t work, you consider you might be stupid. Of course, since even the most self-punishing of us has strategies for avoiding the cloaca of stupidity, there are recourses such as blaming the instructor (as in “Walker Sawyer is a know-nothing prick”) or blaming higher education (“I hate school!”). But when I fell asleep at home while trying to read philosophy for the first time in my life, or fell asleep in Professor Sawyer’s class, or went to sleep in my mother’s car instead of going to class, even when parked just a block away from the classroom building, I didn’t fault Walker Sawyer. And it never occurred to me to “hate school.” I just wanted to sleep, and sleep.

At the end of August, I quit my hospital job several days early, thinking it was time to “wake up” and study for my philosophy exam, especially since the whole grade would be determined by that final exam. I pored through my books, filled out my 3 x 5 cards, and gobbled the snacks my mother would bring up to my room. It was like old times, like the best days of high school. My class notes were, to say the least, cursory, and there was no class chum to call for help because I hadn’t learned anybody’s name, let alone made any friends. But I was working and it was coming together, according to plan.

On the third day, the day of the exam, my plan called for a final six-hour push, which would end around four p.m., giving me plenty of time to shower and eat and relax before the exam at seven. I set to studying early enough that morning, but there was an odd feeling about the house. For one thing, the television downstairs droned on, well after the end of the morning news shows. After I’d worked a couple of hours, I went downstairs for a fresh cup of coffee. The television was still on, and my mother was transfixed before it, still in her robe, which was unheard of.

“What’s up?” I said. “King’s march on Washington. It’s really happening,” she replied, barely turning toward me.

I peered into the television screen. I walked a few steps forward to get a better view. Look at all those people on the Mall; there must be thousands and thousands. “Look, there’s Harry Belafonte,” I exclaimed, inching closer. But then I jumped back. No, no, no, Bobby, I said to myself. You have an exam tonight. You have mucho studying still to do. This may be Martin Luther King’s march but it’s the Devil’s work: the Devil wants you to fail and this is his great temptation. In just this way I talked myself back to my desk.

I studied some more then came downstairs again, looking for lunch. I was prowling in the refrigerator when my mother sighed, “I never thought I’d see this day.” She told me the estimates of the crowd, and as if to corroborate her, the television flashed another panoramic view of the seas of people flanking the reflecting pool. She rattled off the names of the politicians and celebrities. We marveled at which white folks had shown up, mentally entering their names in an honor roll. She told me who had already spoken and who had been good. I tried to make a sandwich while listening to my mother and Walter Cronkite, while riveted by images of people, a rainbow of people, some stylish in suits, some militant in overalls, all swept up in the cause, all sweeping me far away from who philosophized what before Socrates had his say.

“I’ll call you when King speaks.” Promising that was my mother’s way of sending me back to my books. And I went. But now I was wondering how Professor Sawyer could possibly have scheduled his exam the same day as the march. How unfair! How unaware! Was he so ensconced in his ivory tower that he didn’t see the conflict? Didn’t he want his students to watch the march—maybe even go to the march? Why hadn’t he rescheduled, why hadn’t we students petitioned that he reschedule?

We students. I shouldn’t have gone there in my flailing about. I didn’t need to be fuming about what kind of people could study ancient philosophy during the March on Washington, and who could take an exam as if nothing else were going on in the world that day. And it was not helpful at all for me to begin considering that I wasn’t a real student, the proof of it being that I could let King and all the rest distract me, hopelessly. But I considered that, and considered, too, that I had studied enough. Knowing that wasn’t right, I studied thirty minutes more. Then I closed my books and, taking my fate into my own hands, went off to listen to Martin.

My philosophy grade arrived a few weeks later to my college mailbox in the East, the same mailbox which had harbored so many other momentous messages in less than a year. I had passed! I had said to hell with studying, and I had joined the huge flock in Washington—no! the million-fold brethren around the world!—who had gathered to hear Martin preach. With them, I followed Martin to the mountaintop; with them, I shouted “Amen!” to Martin’s “I Have a Dream, for all God’s children!” Yes, I had heard all that, I was there for that. And by golly I had passed philosophy, too.

But it turned out that passing wasn’t enough. As a dean explained, the college only accepted grades above C from other institutions. Stunned, I just stared at him while it sunk in on me that I was still a credit short, that somehow I had to try all over again to make up a course. For an instant, I thought about telling the dean that the philosophy course only required a final exam and that the exam was on the very day of the March on Washington and that, and that. . . But even I knew what that would sound like, especially coming from one of the college’s five black students. So I gathered myself and went my way.

I thought about going to the library to call my mother with the news. But I didn’t. I didn’t need to start the new year by contorting myself into the telephone booth which before had been my favorite place for reporting disasters. And I didn’t need her blues laugh, for I had learned my own. The voice in my head wasn’t churning through some blues now, though; it was chanting. And the words were, “Martin, Martin.”