The Future of Libraries: Embracing Change in the Digital Age

A Bicentennial Essay by Christina Bleyer, PhD, College Librarian, Associate Vice President of Libraries and Digital Learning, Director of Special Collections and Archives, Watkinson Library

As Trinity College stands at the threshold of a new century, it is imperative to ponder the future of libraries and their place in society and academia.

At the nexus between traditional media and new technology, libraries find themselves at a crucial juncture. The physical book, once the cornerstone of libraries, now shares its prominence with digital resources. However, the role of the printed book remains vital. While digital formats offer convenience and accessibility, the tactile experience and permanence of books continue to hold appeal. In the next century, I foresee libraries continuing to offer a blend of physical and digital collections, catering to the diverse preferences and needs of patrons. And there are both opportunities and challenges to that storyline.

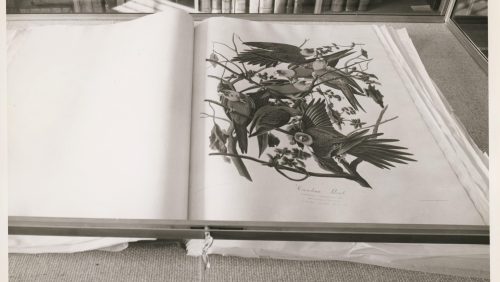

The digital revolution has undeniably alleviated the strain on physical storage. With the advent of digital repositories and cloud-based solutions, libraries can now preserve vast amounts of information without the need for extensive physical infrastructure. However, this does not diminish the importance of physical spaces within libraries. Beyond serving as repositories of knowledge, libraries serve as hubs for collaboration, research, innovation, and academic discourse. The physical space of libraries will continue to evolve, embracing flexible layouts and advanced technologies to accommodate the changing needs of patrons. I often think of libraries as the family rooms of institutions—a safe space, that through music, art, books, technology and social interactions fosters the creation and exploration of ideas leading to the development of new knowledge. At our Trinity College Library, we have taken several steps to become this exploratory family room space. We have transformed several areas to include more art, especially artwork by students. We host several musical performances each year and we have set up more exhibit spaces for our special collections and archives. We have spaces to experiment with virtual reality, AI, and 3D printing, and recently we established an arts and crafts supply library where we have sewing machines, yarn, crochet needles, kits, paint, paper etc. We have also created an area for patrons to work on their crafting projects and we even sponsor an active student crochet club. This April, we will open our seed library where anyone can come and select seed packets to grow herbs, flowers vegetables etc. Our library is more than a storage space for books, it is a space where inspiration takes place and ideas come to life.

For scholars, digital technology has revolutionized research in profound ways. AI tools for research combined with access to vast digital archives and databases has made the work more efficient and convenient, enabling scholars to explore interdisciplinary connections and access resources from across the globe. Knowledge sharing has also been facilitated through digital platforms, allowing scholars to engage in real-time collaboration regardless of geographical boundaries. However, with the proliferation of digital information, scholars now face the challenge of discerning the credibility of sources. The abundance of information available online requires scholars to develop critical thinking skills and digital literacy competencies to navigate this vast sea of data effectively. Our team of research and instruction librarians share their expertise in digital literacy including AI tools with individuals in the Trinity community and beyond on a daily basis but also with groups through workshops and other hands-on events.

Cognition, too, continues to adapt and evolve in response to digital technology. The digital age has reshaped how we process and retain information, with attention spans potentially shortening and multitasking becoming more prevalent. However, it has also opened new avenues for cognitive enhancement, such as interactive learning tools and adaptive learning platforms. As we progress into Trinity’s third century, educators and scholars must remain vigilant in understanding how digital technology influences cognition and adapt teaching and learning strategies accordingly. Our team is a font of knowledge for using digital tools and platforms in teaching and learning as well as in digital scholarship projects. The Watkinson Library in collaboration with the Hispanic Studies Department and the Center for Hartford Engagement and Research (CHER) was recently awarded a grant for our oral history project, Voices of Migration. This project uses the open-source digital tool, OHMS (Oral History Metadata Synchronizer) to index oral histories in such a way that they become a more convenient scholarly resource. Notably, the oral narratives can be searched and specific sections, viewed.

In terms of preserving knowledge, digital repositories and online archives have democratized access to information, ensuring that knowledge is not restricted to the confines of physical boundaries or by socioeconomic factors. Digitization has made it possible for libraries and in particular, special collections and archives to change the ways that they collect, preserve, and make archival materials accessible. The post-custodial theory of archives, for example, envisions that “archivists will no longer physically acquire and maintain records, but…will provide management oversight for records that will remain in the custody of the record creators” (Society of American Archivists Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology). This model departs from the traditional theory and practice of acquisition based on physical custody of records and recognizes that information is not always contingent on its original physical form. Because we can digitize materials and make them accessible online, there is not a need to remove them from the community in which they were created. Instead, partnerships are formed between archives and organizations where the organization maintain physical and intellectual custody over their materials while submitting digital copies to the archive for long-term preservation and access.

In so doing, both archivists and partner organizations are experts. Archivists share their professional expertise in preservation, description, and access to help develop the partner organization’s preservation capacity and infrastructure; partner organizations draw upon local labor for digitization work and harness their subject expertise to provide in-depth description of their materials. The resulting product serves the partner organizations’ programming, meets established standards for preservation, and serves as a valuable primary resource for teaching and research. Incorporating the partner organization into the archival process empowers and further invests the local community in the preservation of its cultural patrimony and helps ensure that the historical record remains intact.

At Trinity, The Watkinson Library is currently engaged in digitizing the archive of the late Trinidadian intellectual, columnist, and economist Lloyd Best. The archive is located in Trinidad and Tobago. In traditional archival practice, the Lloyd Best Archive would have been taken physically from Trinidad and Tobago, brought to the Watkinson, and the collection would have been described by an archivist who likely would not have been a part of the Trinbagonian community. Maintaining physical and intellectual control of archival materials while being able to make them accessible allows for what Lloyd Best calls an “epistemic sovereignty” and allows the community to be recognized as they choose to be and not reduced to the opinion of someone outside the community. The impact of being able to collect, preserve, and make archives accessible in a post-custodial manner is profound for the preservation of cultural heritage and, as I have argued elsewhere, allows for a decolonial archival praxis to take shape, The Lloyd Best Archive will be launched at the Lloyd Best Institute of the Caribbean on March 19, 2024, the anniversary of its namesake’s death nearly two decades ago.

The digital realm is not without its challenges, however. Rapid technological obsolescence and the fragility of digital formats necessitate robust preservation strategies to ensure the longevity of digital collections. Libraries must invest in digital preservation initiatives and collaborate with archival institutions and technology experts to safeguard digital resources for future generations. I am proud to say that our digital asset management team has recently established long term digital preservation for our assets. This involves storing copies of digital assets in several places and regularly running checks on the files to make sure they are not degrading.

Even with the changes brought about by the digital age, libraries remain invaluable institutions for knowledge preservation, dissemination, and engagement. By leveraging emerging technologies, fostering digital literacy, and transforming spaces, libraries can continue to support communities and serve as beacons of learning and intellectual exploration in the 21st century and beyond.