Reflecting on Community Engaged Research Experiences with Emma Hersom ‘24

The moment I first stepped foot on Trinity College’s campus, I was struck by the campus’s seamless immersion with the city of Hartford and its connections with the communities that call Hartford home. I was deeply involved in social justice advocacy and community engagement in high school and was eager to expand my passions through learning from and engaging with diverse communities. I knew I wanted my experience at Trinity to be part of further connecting the campus to the Hartford community. I applied for the Spring 2021 Liberal Arts Action Lab as a first step toward working with the Hartford community as a student. My experience with the Liberal Arts Action Lab was so fulfilling that by the end of the following semester, I applied to the Community Learning Research Fellows program to continue my commitment to community engagement and research. Throughout both research experiences, I not only deepened my connections with fellow students, professors, and community members, but I learned that I could combine my love and passion for social justice with academia and research in meaningful ways that contributed to positive social change, and helped advocacy organizations further their goals.

The Liberal Arts Action Lab is an educational partnership that allows students, faculty, and community partners to collaborate to answer research questions on Hartford. I worked on the School Nutrition Project in collaboration with food justice community partner Grow Hartford. The goal for our project was to examine how Hartford Public School’s (HPS) nutrition plan aligned with food justice goals, and to determine how power players in the food sector impacted the plan. Working with the organization and Trinity alumna Shanelle Morris ’16, we designed a power map that identified key players for Grow Hartford to work with moving forward. We also compiled nutritional data on the meals being served in HPS, conducted an analysis of how the relevant criteria under Grow Hartford’s food rubric has been met by HPS, and created a web page summarizing our findings and research process. Through our analysis of nutritional data and Grow Hartford’s food rubric, we determined that while HPS has improved their school food program, more work needs to be done in HPS to ensure that meals served are even more nutritious, youth-centered, and ethical. This analysis has helped Grow Hartford to continue their advocacy for better food in HPS.

My Liberal Arts Action Lab team consisted of five students; four from Trinity and one from Capital Community College. Our first course of action in the project was communicating with our community partner, Grow Hartford, to learn more about their organizational goals and ensure that the collaborative path our team was envisioning aligned most strongly with their wishes and needs. Following that initial conversation, our team began to reach out to Hartford Public Schools’ Food Program staff to collect more information on the food being served in HPS, the nutritional content of the foods, and a list of the main distributors. By the end of the semester, after countless conversations with those involved in HPS’ food programs, completing readings, and working with our community partner, our power map identified individuals that were the most important in providing Grow Hartford with the information necessary to further develop their mission and reach their goals. The power map was created by measuring the level of power each person had regarding school food decisions and the level of engagement our community partner had with them at the time.

Since this was my first research experience, I learned a significant amount from my time with the Liberal Arts Action Lab. I learned that food plays such a significant role in schools, yet educators often overlook its influence, despite its effects on student’s health and performance, administration, the environment, and culture. I also learned about the importance of illuminating school food programs to prevent contributing to stigmatization and social exclusion of families experiencing food insecurity. This research made me reflect on my own experiences surrounding food insecurity. For a while, I chose not to access my school’s food program because I was afraid of enduring the stigmatization and potential bullying that is unfortunately associated with these programs. In response to this, our research exemplified the importance of receiving input from families experiencing food insecurity when developing school food programs.

The following year, I continued my commitment to community engagement through Community Learning Research Fellows, where I worked with another Hartford community partner, James Jeter. James is the co-founder of the Full Citizens Coalition, which strives to expand the right to vote for those incarcerated in the state of CT and beyond. My research for this project was centered around uncovering the relationship between disenfranchisement and second-class citizenship. I focused on incarcerated people in the United States with an emphasis on CT. This research culminated in the creation of several internal documents for the organization to utilize throughout their advocacy campaigns, as well as a web page summarizing my findings. I am continuing to collaborate with James and Full Citizens Coalition this summer on a new research project related to the effects of disenfranchisement.

The following year, I continued my commitment to community engagement through Community Learning Research Fellows, where I worked with another Hartford community partner, James Jeter. James is the co-founder of the Full Citizens Coalition, which strives to expand the right to vote for those incarcerated in the state of CT and beyond. My research for this project was centered around uncovering the relationship between disenfranchisement and second-class citizenship. I focused on incarcerated people in the United States with an emphasis on CT. This research culminated in the creation of several internal documents for the organization to utilize throughout their advocacy campaigns, as well as a web page summarizing my findings. I am continuing to collaborate with James and Full Citizens Coalition this summer on a new research project related to the effects of disenfranchisement.

CLRF required students applying to submit a research project proposal and propose a potential community partner for the project. I loved the freedom to conduct research on whatever I was passionate about, though initially I was intimidated by this independence. I knew I wanted to do research related to mass incarceration and its systemic causes and effects, as it has always been a part of my advocacy, but I still wasn’t certain of the specifics. My faculty sponsor, Professor Terwiel, connected me with James and the Full Citizens Coalition.

James and the Full Citizens Coalition were interested in exploring the ways that the Thirteenth Amendment has been used to reproduce unequal citizenship through disenfranchisement. Additionally, they were interested in finding out why Connecticut’s voting laws for incarcerated people differ from Maine and Vermont, the only two states that allow incarcerated people to vote. Moreover, why has the United States in general so drastically diverged from other progressive but historically similar nations on questions of incarceration and voting?

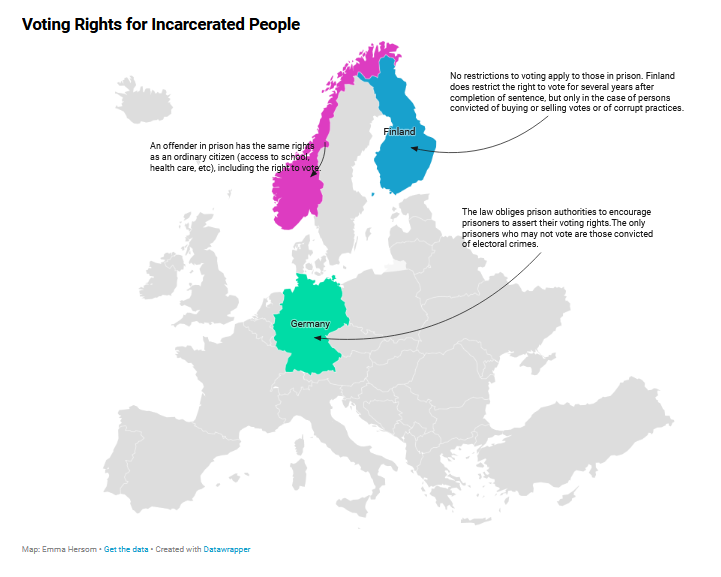

To answer my community partner’s research questions, I looked at a wide variety of sources: book chapters, podcasts, databases for legislative history, videos, news articles, websites, and more. As I continued throughout the semester, I learned even more about the ways that the racist origins of most felony disenfranchisement laws mirror the expansion of new legal codes that aim to incarcerate African Americans. And, while the Thirteenth Amendment is federal, constitutional law, many decisions about punishment and citizenship are made at the state level, which creates confusion for those who are incarcerated about their voting eligibility. Another significant portion of my research was dedicated to conducting an international comparative study between Norway, Finland, and Germany, who have very successful, progressive prison systems and have not disenfranchised or dehumanized incarcerated people in the same ways that the United States has.

Overall, the biggest takeaways from this research was that the US has the ability to delink incarceration and disenfranchisement, because other countries provide successful examples of this practice. The first step would require overcoming a racialized and exclusionary conception of citizenship. This summer I am continuing to collaborate with James and Full Citizens Coalition on a new research project related to the effects of disenfranchisement.

My engagement with the community through the Liberal Arts Action Lab and the Community Learning Fellowship has taught me that research, in many ways, can be a form of advocacy. Through these projects, I gained valuable skills and knowledge, and I also formed meaningful connections with community partners, professors, and fellow classmates. As a college situated in the middle of a large city, I believe Trinity students, professors, and staff have a duty to prioritize connecting with surrounding communities in meaningful ways.